A project by Lorena Wolffer

Curated by María Laura Rosa

This exhibition contains explicit sex and sexual abuse accounts.

It is not suitable for minors.

Fuera de escena (Off-stage)

1974 – Cumpleaños (Birthday)

1992 – Baño (Bath)

Fuera de escena 1974 – Cumpleaños (Birthday).

At 38, I remembered that my biological father had abused me.

I was at my first girlfriend’s house when I recalled it.

It happened while I was watching an episode of the series In Treatment.

Years later, I learned that the abuse had started when I was around 3 years old.

This Super 8 film is from my third birthday.

I don’t remember it, just like the rest of my childhood.

Mexico City, Mexico 1974

Fuera de escena 1974 – Baño (Bath)

I practically have no memories of my sexual interactions with men.

But I do remember the rage.

The impulse to hit that I sometimes wasn’t able to control.

This is a video I don’t remember recording and that I suppose was for a piece.

In it, I discover that I asked a friend to bathe me and my then-boyfriend to record it.

Boston, Massachusetts, United States, 1992

On Darkness, Light, and Other Effects of Trauma

María Laura Rosa

The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives.

Audre Lorde, Poetry Is Not a Luxury, 1977

The works that Lorena Wolffer presents in Archivo oscuro (Dark Archive) document her encounter with aspects of her life that she had forgotten and her search for their meaning and their integration into the continuum of her reality. In this body of work she reflects on the act of remembering as one of the elements that constitutes our identity and on forgetting as a defensive action of our subjectivity that allows us to continue with our existence. What we forget, however, then reveals itself as a powerful force that subtly affects our daily choices, our feelings and our regrets.

The word archive has various definitions. Some refer to the space where memory is preserved, while others emphasize the authoritative weight implicit in the act of archiving, presupposing that what is archived has a certain importance simply because it is located in a space that safeguards memory. In 1969, Michel Foucault offered a definition of the term that I find compelling because it allows us to consider the role of language in constructing narratives: “the archive is first the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events”1. It is discourse that determines the singularity of that which is worth archiving. Foucault emphasizes the enunciative

dimension of that which is archived, and it is this dimension that confers on everything that is preserved a capacity to produce meaning that is renewed time and again. In this way, we identify things that interpellate us in a specific context, generating the conditions of possibility for this process of identification to occur.

Yet how can we approach an archive that remains in darkness, in the impenetrability of language? How can we interpret images that divert memory, and that feel alien even to the protagonist of their narrative? The consequence for someone who encounters this experience of opacity in their own life is that they immediately become an investigator, searching for even the smallest details that can provide them with information about that moment, that person, or that object. This is the position that Lorena Wolffer has assumed in relation to a series of images from her personal archive about which she recalls only a few fragmentary facts or nothing at all. Brief narratives accompany all the works presented here, constituting what Foucault described as: “the appearance of statements as unique events”. These are the elements that provide the present context that sustains the past.

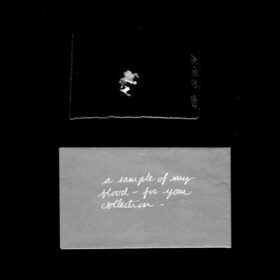

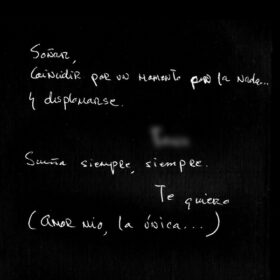

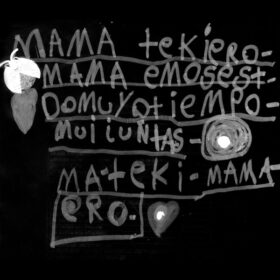

Desmemorias (Lost Memories)

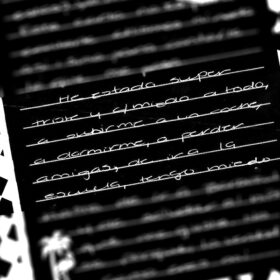

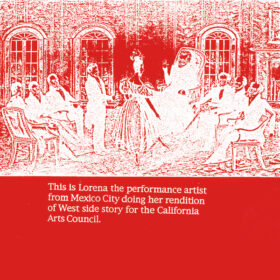

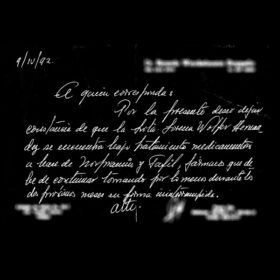

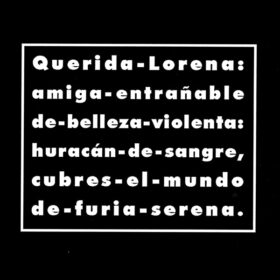

As we move through Desmemorias (Lost Memories) (2024) we realize that that past which has been forgotten or is recalled only in fragments related to traumatic personal experiences, that is, the act of forgetting is closely tied to mechanisms of resilience that made and continue to make possible existence in the present. The artist describes the work in the following manner: “Lost Memories is comprised of 20 photographs, postcards, letters, texts, and doctor’s prescriptions from different periods in my life, from my early youth up to a few years ago, that I found in my boxes of personal items. I don’t remember anything about those that appear in black and white, and I only recall one isolated detail—like the pattern of the quilt on my bed or the shirt that I was wearing—in relation to those that appear in red and white”2. The neutrality or the temperature of the color provide clues to the affective intensity of memory, that is, the role that our emotions play in the act of remembrance. And likewise, in the act of forgetting.

Desmemorias leads us to reflect on the role of affect as a mechanism of selection in the act of remembering. In this context, we can ask whether this act is informed by gender, since we live in patriarchal societies in which both cis and trans women are the object of multiple types of violence. If we reflect on the quotation from the Afro-American, feminist, lesbian, and activist poet Audre Lorde with which this text begins, I ask myself and I ask you: what is the quality of the light with which we observe our lives—as cis and trans women—and its effect on the way in which we live, and even more, on the changes we hope to achieve through our lives?

Undoubtedly this light is shaped by spaces free of violence, by moments when our bodies bear no marks of violence, and by contexts in which our freedoms as cis and trans women have not been violated. Clearly, what we choose to remember or forget, what we allow to enter the realm of language, that realm of “I am, here I am, I call myself, I identify myself, I construct myself in narratives”, is powerfully shaped by gender, race, class, and the violences that we suffer as a result of all these factors.

In Desmemorias we participate in the mapping—a method dear to Wolffer—of memory and of forgetting, a process that opens up intimate spaces that testify to latent or explicit violence, accidents, medical treatments, letters, objects, people, and moments. Paths of love and pain, of agreements and disagreements. Light and darkness often appear within the same narrative, while at other times the light brings on darkness, and on occasion pure darkness dominates the archive, revealing a lack of porosity, an impermeability to light. Both are symbolic referents for the states of the gendered body and soul.

Cumpleaños, Baño, Baby Love (Birthday, Bath, Baby Love)

The entry into a personal archive—and we might ask ourselves if all archives aren’t personal on some level, though this isn’t the place to answer that question—exposes us to various risks related to the senses. The archive may emit odors that trigger personal memories,or sounds that provoke recollections. Taste is less likely to be evoked, although anything is possible. Perhaps vision is the sense that is most readily involved, and although we don’t want to succumb to its tyranny, it is very possible that what we see in this receptacle of the past may interpellate us on a personal level.

The cartographic journey that we initiated with Desmemorias serves as the prelude to three videos that Lorena Wolffer presents as part of her personal archive. In them, she tells a story that we have already intuited: abuse, hypersexualization, objectification, vulnerability. It is then that we begin to understand that those gestures of forgetfulness are traces in a chain of events. The testimonial narratives, in the three pieces, are veiled and unveiled in a nervous, constant rhythm by means of unsettling sounds or painful silences.

Archivo oscuro continues Lorena Wolffer’s work over the course of various decades on the subject of violence against cis and trans women, and the use of testimonies as a vehicle to raise awareness regarding the position of vulnerability and inequality that we occupy in Western societies. This darkness may refer to multiple elements: the injustice with respect to the resolution of cases of abuse, feminicide, and transfeminicide, or the denial of their existence–sadly present in my country, Argentina, where the president wants to return to the notion of homicide for cases of femicide 3 —, or perhaps the erasure of cis and trans women from the concepts of humanity, human rights, liberty, equality, justice, and other universals.

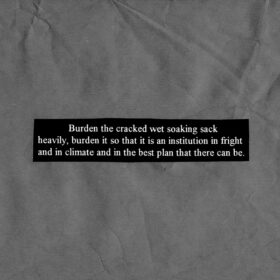

However, I also believe that the darkness referred to in Wolffer’s archive can be linked to traumatic factors, understanding trauma as a shocking event that the psyche of the person affected cannot assimilate, comprehend, or process. This leaves a lasting mark that emerges in later life, triggering disproportionate or objectively unjustifiable reactions. The deferred effect—as Sigmund Freud called it—refers to the situation that liberates a traumatic wound, that has long gone unnoticed by the person involved. In Fuera de escena: 1974 – Cumpleaños (Off-Stage: 1974 – Birthday, 2024) Lorena Wolffer recounts the delayed effect linked to her abuse by her father. In Fuera de escena: 1992- Baño (Off-Stage: 1992 – Bath) (2024) she describes the rage and desire to hit that was triggered in her by certain heterosexual relationships. The exquisite corpse Baby Love (2024) brings together heteropatriarchal phrases that resonate with many of us, some so naturalized that we overlook them, and that reveal the structural violence we experience every day as cis and trans women.

Collective Trauma

Although trauma and the traumatic have been extensively studied in psychology, aesthetics and art history have paid less attention to them. Much of the existing research in the artistic field focuses on the consequences of concentration camps in fascist regimes and, particularly, on the genocide of the Jewish people. The feminist art historian Griselda Pollock has dedicated a significant portion of her work to the analysis of the traumatic legacy of the Shoah in certain artists, a process that has led her to question the delay in addressing this topic. In a 2007 lecture she comments: “The new awareness of traumas of the Other are themselves the by-product of the effect of feminist intervention, at first challenging gross sexism and discrimination, but soon realizing that each of us is a complex weave of many relations and positions, shaped in so many often contradictory alliances, histories and antagonisms: race, class, sexuality, ability, geopolitical situation and so forth. (…) But it has taken time for the complexities of such multiple weavings of power and difference to become thinkable or theorizable. It has also taken time for us to weave together the trauma of fascism’s battle against feminism with its war on those it racially, physically and sexually othered. Artists have also led the way in changing our sensibilities and thought and in dialogue between the aesthetic events and the theoretical practices, the radical novelty of both becomes generative of the potentiality for further change.”4

Following Pollock’s reflection, I would like to consider how much of Lorena Wolffer’s work—whether collectively produced or personal in nature, as is the case here, —has triggered experiences that have led to the elaboration of the traumas caused by abuse and the various forms of gender violence that we suffer as cis and trans women. As a feminist and art historian I have been studying Wolffer’s work for more than a decade yet, perhaps, I was not prepared to pause and think—taking up Pollock’s statement above—about the specific ways in which her artistic and activist proposals make conscious the traumatic experiences that affect collectives of cis and trans women. It is now with Archivo oscuro that I perceive the movement from her personal history to a meeting place where others can embrace the traumatic in order to transform it. The space of art and aesthetics functions as a vehicle for sharing traumatic experiences with other subjectivities.

Lorena Wolffer immerses us in a visual corpus of affective dimensions, whose traumatic nature has been inscribed for decades in the bodies of cis and trans women. Since its radical eruptions in the 1960s, feminism has been denouncing the fact that this structural violence responds to cultural factors related to the construction of what Segato has called the mandate of masculinity. Early on and in consonance with those feminisms, artists have participated in this denunciation through their experimentation in diverse visual languages. Thus, for over five decades we have borne witness, in the artistic field, to the denaturalization of quotidian practices of objectification, in which art has served as a key vehicle of consciousness raising. The collective work Repositorio (Repository) (2025) is related to this latter aspect, since it provides a space where the public can record their experiences of memory and oblivion, in the form of an archive, as part of the exhibition.

For this reason, I consider it important to reflect on the collective traumatic experience endured by cis and trans women, and on the expanding magnitude of this violence, particularly in regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean, where the respective statistics have reached catastrophic proportions: eleven women assassinated every day, according to data from 2024, and 1841 transgender people assassinated in that same year. In this context, Archivo oscuro represents a transformative, healing force, in its ethical and poetic power and its luminous potential—even in opposition to its title– to achieve changes in our everyday lives. We must continue fighting so that our memories, that constitute our identity, as well as those things that we have forgotten, can be linked to equality and the freedom to live a dignified life.

- Michel Foucault (1972), The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, New York: Pantheon Books, p.129.

- Lorena Wolffer, Desmemorias, project statement, 2024, https://lorenawolffer.net/2023/01/05/synapse-3/.

- In Argentina, the concept of femicide was incorporated into the Penal Code in December 2012, through

Law 26,791. This reform modified Article 80 of the Penal Code to increase the criminalization of certain

homicides, particularly those related to gender-based violence. Unlike in Mexico, the term used was

femicide, not feminicide. - The lecture is compiled in the following publication, from which I have taken the quote: Griselda Pollock,

(2008), “From Feminist Interventions to Feminist Effects in Arts Histories: A Case Study of Feminist Virtuality

and Aesthetic Transformations of Trauma”, in Xabier Arakistain and Lourdes Méndez (eds.), Artistic

Production and The Feminist Theory of Art: New Debates I, Vitoria: CC Montehermoso, p. 292.

Translation: Karen Cordero Reiman

Lorena Wolffer

For over thirty years, the work produced by artist and cultural activist Lorena Wolffer(Mexico City, 1971) has been an ongoing site for enunciation and resistance at the intersection between art, activism and transfeminism. Her practice revolves mainly around gender and advocates the rights, agency, and voices of women, LGBTQIA+ communities and people with non-normative identities. From the creation of radical cultural interventions with various communities to pioneering pedagogical models for the collective development of situated knowledge, these projects are produced within an inventive arena that underlines the pertinence of experimental languages and displaces the border between so-called high and low culture. Her work—a stage for the voices, representations, and narratives of others—articulates cultural practices based on respect and equality.

—

María Laura Rosa

Doctor of Contemporary Art, UNED (Madrid) and Master in Contemporary Art, UNED (Madrid). Adjunct Teacher and Researcher at CONICET through the Instituto Interdisciplinario de Estudios de Género at the Facultad de Filosofia y Letras, UBA. She teaches the Aesthetics chair at said faculty and heads the Latin American Art chair in the Bachelor’s program of Curatorship and Art Management, ESEADE. Her research focuses on issues related to art and feminist theory in Argentina and Latin America, mainly in Brazil and Mexico. Author of Legados de libertad. El arte feminista en la efervescencia democrática (2014). She has written about art and feminism in indexed journals with scientific refereeing, art catalogs, and has recently curated the following exhibitions: Mitominas 30 años después, Centro Cultural Recoleta (June-July, 2016), La persistencia del agua. Grete Stern en diálogo con artistas contemporáneas, Museo de Arte de Tigre (April-June, 2016), among others.

Curator:

Coordination MUMA:

Design:

Web Programming:

Catalog Editing:

Thanks to:

María Laura Rosa

Yolanda Benalba

Lorena Wolffer

Elisa Rugo

Vanessa López/La Duplicadora

Irmgard Emmelhainz, Jonathan Sainsbury, Kira Sosa Wolffer, Kyzza Terrazas, Lucero González, Mirna Calzada, Tatiana Espinasa & Vanessa López.

The pieces that make up Desmemorias are for sale at DOMICILIO gallery.