As an introduction or starter

Despite the antiquity, abundance and quality of still lifes that have been painted throughout the history of art under different styles, techniques and purposes, this artistic genre has not received the critical attention it deserves, particularly when concerning its contemporary exponents. The huge importance given in Mexico to mural painting, which is mostly masculine, public and political, disregarded easel painting appreciation, especially still lifes, considered to be the epitome of the feminine, domestic and decorative par excellence.

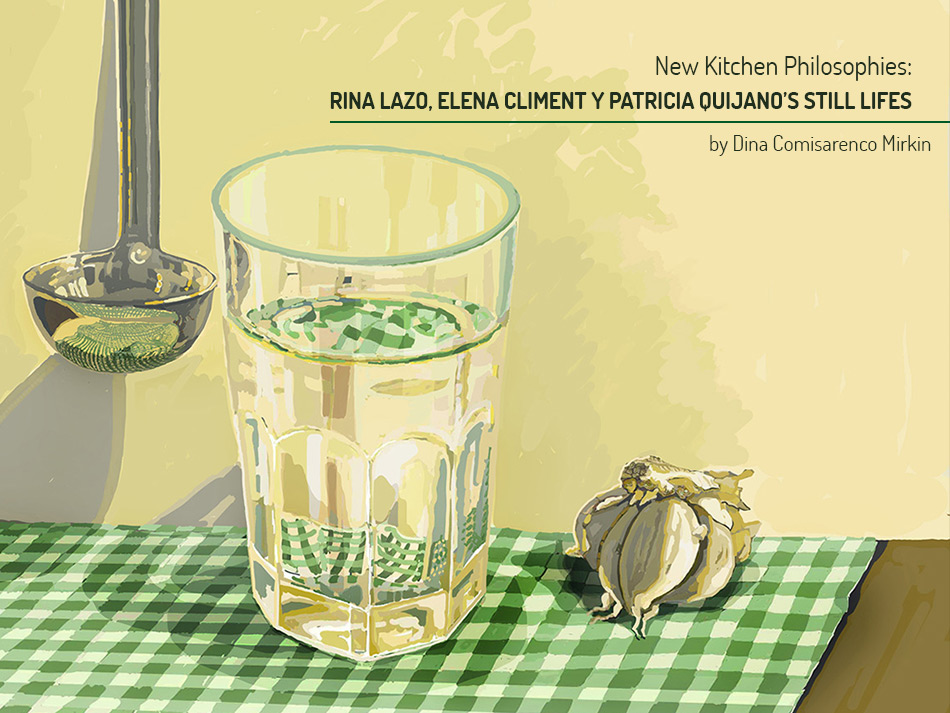

We aim to show with this exhibition devoted to some of the still lifes painted by three contemporary visual artists, Rina Lazo (1923), Elena Climent (1955) and Patricia Quijano (1955), that their works do not belong to such stereotypical dichotomies, in order to originally and productively place themselves instead, halfway between the paradigm of art for art’s sake tradition, and the conception of painting as an ideological device of political struggle, in this case, in relation to genre positions and ideologies.

Parting from the ironic question posed by the great poetess Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz in the 17th century, in regard to “What can women know other than kitchen philosophies?”, we intend to show that it is precisely in still life painting, despite the generalized historiographic contempt towards it, where female artists frequently found the necessary elements to overcome prejudice, express their own world view, and resist by these means the several restrictions women have been put through in history..

Background or a Mouth-watering Starter

Before we dive into our main topic, we must stress that during the 1920s there was a vast tradition of still lifes produced by outstanding female artists in Mexican painting. Some representative works such as Tina Modotti’s Composición: mazorca, guitarra y canana (Composition: Corncob, Guitar and Canana) (1928); María Izquierdo’s Naturaleza viva (Living Nature) (1946); Olga Costa’s La vendedora de frutas (The Fruit Seller) (1951); Frida Kahlo’s Naturaleza viva (Living Nature) (1952) and Remedios Varo’s Naturaleza muerta resucitando (Resurrecting Still Life) (1963), amongst many other examples, show the richness and vitality of the artistic´s genre.

Far beyond the mere talented use of the main features of still life painting (representation of food, kitchens, served tables, kitchenware, flower vases, fruit bowls, vanitas) and/or bodegones (which generally only include food, drinks and kitchenware), in these works, it can be observed, that the female painters managed to transcend the exclusive decorative intentions with which this genre is associated, and that they reached broader meanings ranging from political allegory, national identity, working women, and the philosophical reflection on life and death, among many other key topics in national art history.

Following the prosperous tradition of women artists in Mexico, Rina Lazo, Elena Climent and Patricia Quijano painted several still lifes, in which a complex variety of creative resources can be seen; moreover, their own personal intentions and the times they lived in, determined how they decidedly broke up with the stereotypes associated to still life as an artistic genre of lesser hierarchy.

The Exhibition’s Varied and Delicious Main Dishes

1. What Rina Lazo Sees Through the Windows...

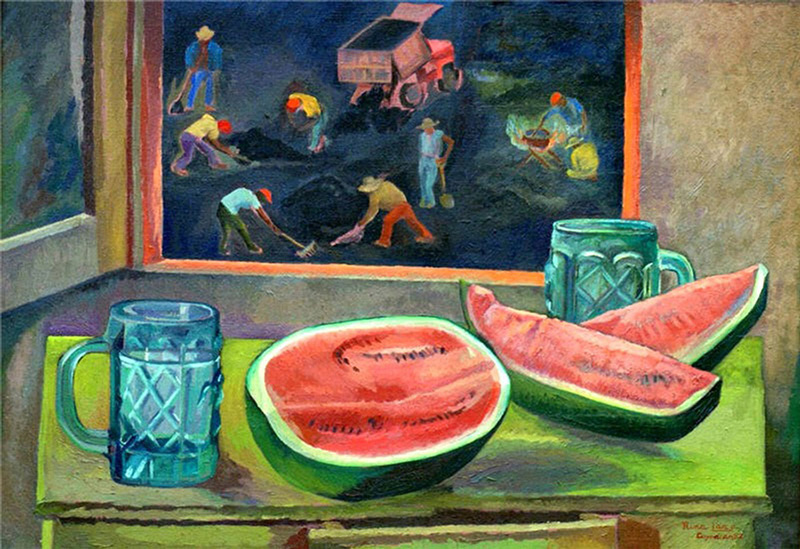

By locating objects in front of windows, in her still life paintings Rina Lazo achieves a visual dialogue between the colorful fruits and the outdoors, which is generally represented by palm trees, moons and trees; in this way, Lazo creates very personal spaces that are neither exclusively interior nor totally exterior, since they transcend both categories by integrating the inside and the outside in a new and porous unity.

It is worth mentioning that in this singular hybridization of still life and landscape, some of Lazo’s works portray urban scenes, as it happens in Tarros y sandías en la ventana sobre el asfalto (Jars and Watermelons by the Window on the Asphalt), in which the artist depicted the scene she saw through her window as a background/picture when, back in time, the coble stoned street in which she lived became paved. The context of the worker’s labor gains a symbolic presence by melting with the domestic indoors of the room from which Lazo paints, thus metaphorically declaring that she is never alien to the social conditions around her, not even when she paints a still life from her room’s window.

Another interesting example of hybridization between still life and urban landscape with a political content in Lazo’s work is her painting Puesto de dulces en la manifestación de nacionalización de la banca (Candy Stand at the Demonstration of Banking Nationalization) (1984); this is a very original work which, despite its playful and festive atmosphere, portrays a very complex stage in Mexican history. In the foreground, Lazo paints a wide variety of regional candies randomly displayed in a foldable table; through their rhythm and colors the candies dialogue with the historical scene at the background: a demonstration at Mexico City’s main square concerning the nationalization of banking, under which the painting was entitled. This original still life, literally located in the public space, clearly transcends the exclusively decorative connotations associated to this pictorial genre, and thus becomes a work with social content.

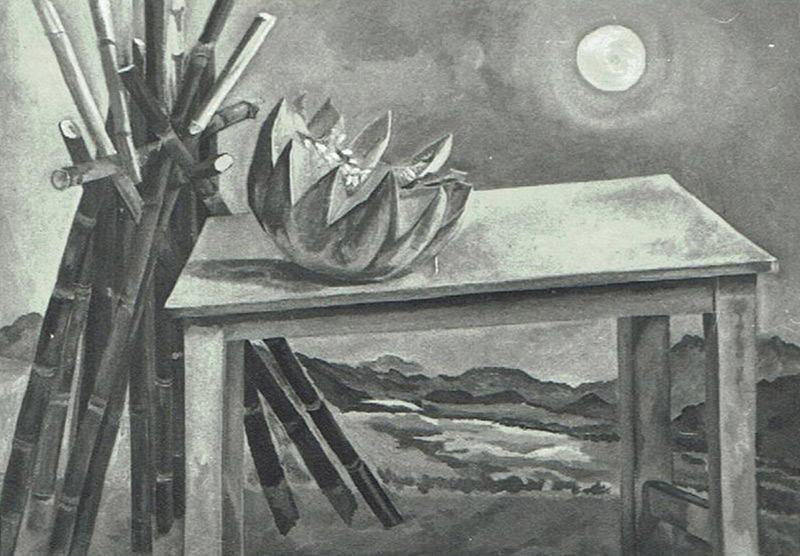

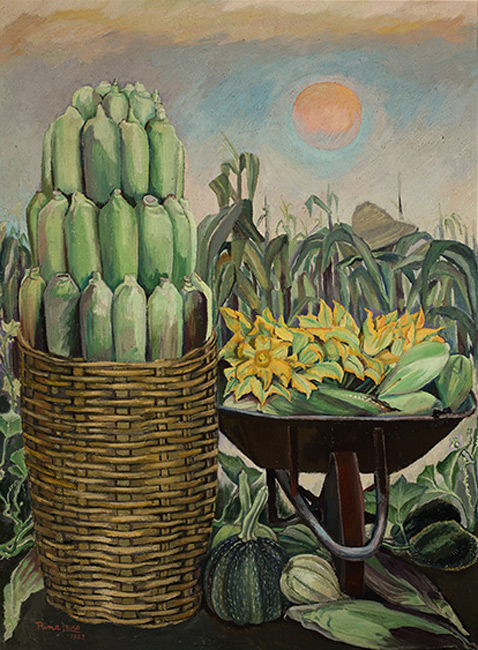

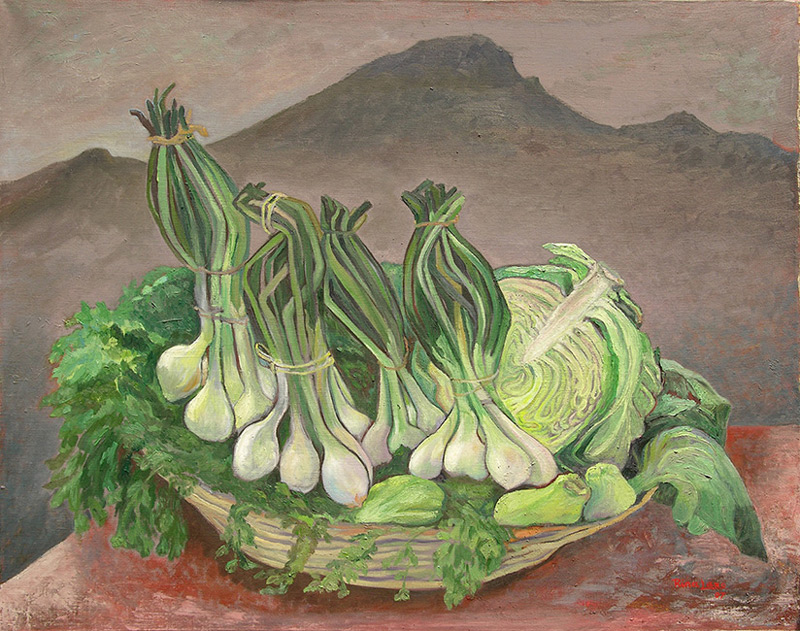

Another sub-group of Lazo’s bodegones within her set of still life/landscape works, seems to continue this process of integrating the inner and outer spaces when she completely gets out of the enclosed space of both the house and the studio as in the former example, and installs her objects amidst rural landscapes. We find this in works such as Piñas y pitahayas (Pineapples and Dragon Fruits), Noche de muertos en el valle de Oaxaca (Night of the Dead in Oaxaca’s Valley), Cosechando elotes (Harvesting Corn) and Canasto de cebollas (Basket with Onions), in which all trace of walls and window frames disappears in order to create instead a fantastic reality in which the objects of nature that were torn apart from their natural environment return to it and recover their primeval harmony, even though they somehow remain isolated and ordered by human action, in this case by the artist herself.

In order to close this set of Lazo’s landscape/still lifes, we will mention there is a further sub-group, in which the artist even trespassed the terrestrial environments in order to cover the sidereal universe, thus establishing interesting metaphors between the fruits’ microcosm and the celestial bodies’ macrocosm. In 1969, right in the time when man landed on the moon, and its TV broadcast which deeply marked a whole generation, the artist painted a series of still lifes located in the outer space that once exhibited, gained much recognition from both the public and specialized criticism. The moon, one of the feminine symbols that the artist had already been using in her still lifes as seen through the windows, found in this new set of works a leading role, making its analogies with the roundness of the fruits placed in the foreground visually explicit, while poetically expressed they reach the clouds.

2. Elena Climent’s Objects of Memory

Elena Climent also traces interesting connections between the public and the private spaces through the still life genre, although in the opposite direction, that is to say, parting from the exterior in order to venture into the soul incarnated in the objects. By means of different creative strategies, ranging from the representation of spontaneous still lifes that she discovers in the urban spaces of Mexico City, to those which are an allusion of the traditional paintings of alacenas and altars, Climent reaches the most intimate spaces related with the objects and memories of her childhood, which she portrays in detail and isolated from their broader contexts, thus transforming them into still lifes with a great evocative force.

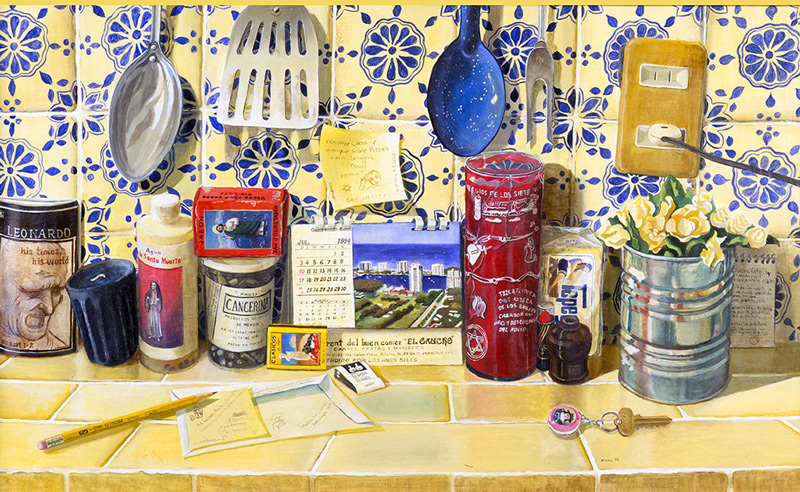

During the 1980´s, on one occasion in which the artist was touring with her family through the city, Climent discovered a house with a painted metallic door, behind of which she discovered a strong pink color curtain printed with blue flowers, glowing with a mysterious light. This vision made her understand that which, in her own words, is defined as the singular “aesthetics of Mexico City”, characterized by the usage of any kind of contrasting objects, most of them of a humble origin, which are lovingly installed and combined by their owners with the aim of individualizing their own spaces, “no matter how small they are,” in order to transform them into “a whole universe”. This ability of turning the most humble and common of spaces into a whole world characterizes Climent’s delicate sensitivity as well; since in her works she manages to express this meaningful popular aesthetics, both with empathy and great respect.

As of this casual discovery, the artist started to go across the city taking pictures of urban corners, where singular and spontaneous “still lifes” appear, formed by hanging pots in the colorful walls of the vecindades, or by an infinity of candies and groceries which are gathered on improvised tables, stores and stalls which, despite their poorness, are wonderfully decorated with flowers and piñatas. With a veristic and popular style, along with an excellent pictorial technique, Climent captures every small detail of the reality she sees, and through it we rediscover Mexico City’s singular iconography with all its naïveté, beauty and exceptional poetic quality.

1. Elena Climent, in “Elena Climent,” Resumen. Pintores y pintura Latinoamericana, Promoción de arte mexicano, year 8, no. 66, 2003, p. 41.

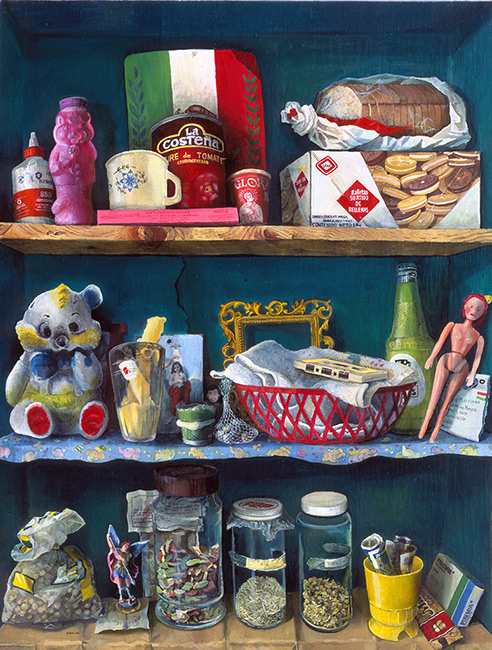

Another favorite motif in Climent’s painting is that of alacenas or domestic cupboards, niches and religious altars, in which a huge variety of objects are placed with a symbolic and communicative intention, captured by the artist with great sensitivity. In these popular traditions and costumes, Climent recognizes a part of Mexican national identity, especially in the altars of the sideways of churches, in which the artist sees how “people appropriate these spaces” and “put candles, relics, flower pots and photos of their loved ones: those alive; those in disgrace; and those who are no more, as well”, thus showing a remarkable spirituality.

2. Elena Climent, in “Elena Climent,” Resumen. Pintores y pintura Latinoamericana, Promoción de arte mexicano, year 8, no. 66, 2003, p. 47.

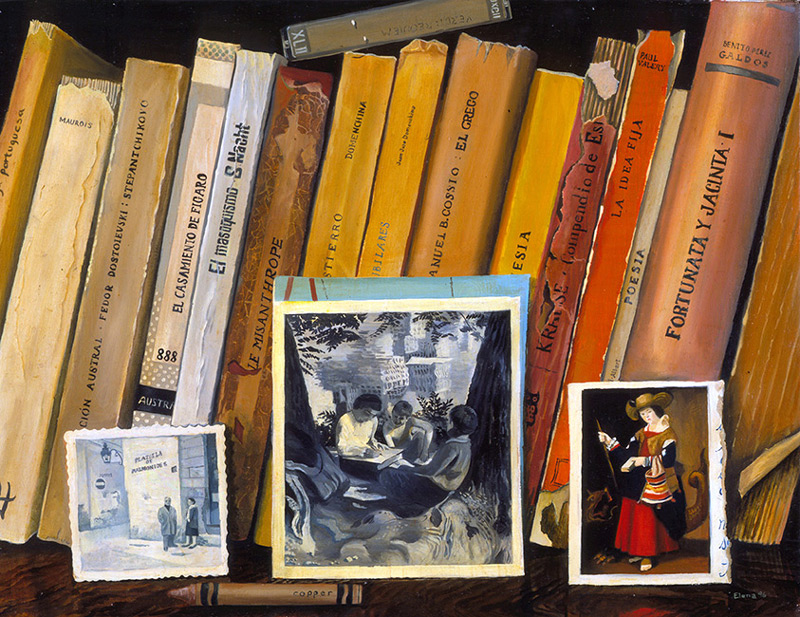

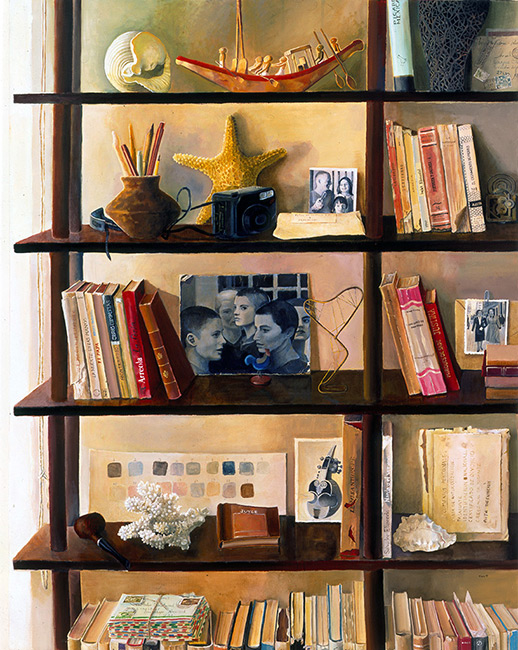

Another outstanding set of Climent’s painting is that which portrays the intimate corners of her childhood home, in which several memories and nostalgias are condensed. The daughter of the outstanding Spanish painter Enrique Climent (1897-1980), a refugee of the Spanish Civil War in Mexico, and of Helen Smoland (1917-1994), who belonged to a Jewish Russian family that migrated first to the United States and then to Mexico, Climent had a happy and stimulating childhood. After the dead of her mother and the imminent sale of the family house in 1994, Climent devoted herself to portray the most meaningful places of her blissful family life, in an attempt of symbolically capturing them through images, and thus trying to evade from the oblivion that brings the passing of time.

Climent then started to depict different scenes that featured kitchen tables, bookcases and night tables, all of them full of decorations, photographs and other objects, generally artistic ones, which resemble the altars of the former series, but which now belong to the more intimate space of her childhood. Despite the concrete references to objects and memories of her own family, the portraits/still lifes by Climent are full of a strong evocative power, which appeal to everyone’s sensitivity, for these images bring our own memories of similar objects and compositions, and through them, of our own spaces and personal stories.

Climent’s singular family´s mestizaje is also frequently alluded to in her original still lifes, in which there can be found family photos, postcards with reproductions of classical works of art, colorful traditional handcrafts, images of Christian saints and Jewish menorahs. By means of her still lifes depicting her family home, Climent achieves truly spiritual portraits of her parents, and by doing so, she alludes at the same time to the rich Mexican identity, formed by several traditions and cultures. Thus, the singular becomes a strong allegory of national identity, integration, the passing of time and of the extraordinary evocative power of objects.

3. Patricia Quijano’s New Allegories

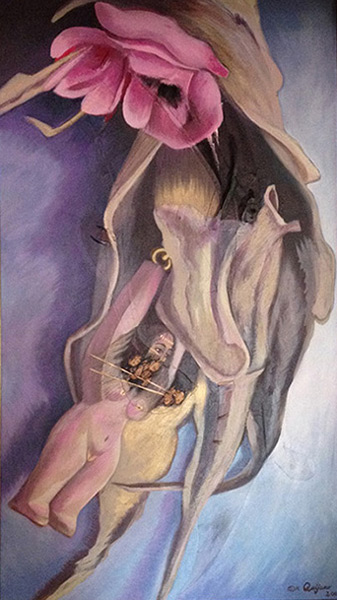

With the passing of time, Quijano’s interest in exploring the impulse of human life led her to paint still lifes in her case, by originally updating the tradition of Frida Kahlo’s works, just as we exemplified in the first part of the exhibition, as a metaphor for alluding to reproduction and sex.

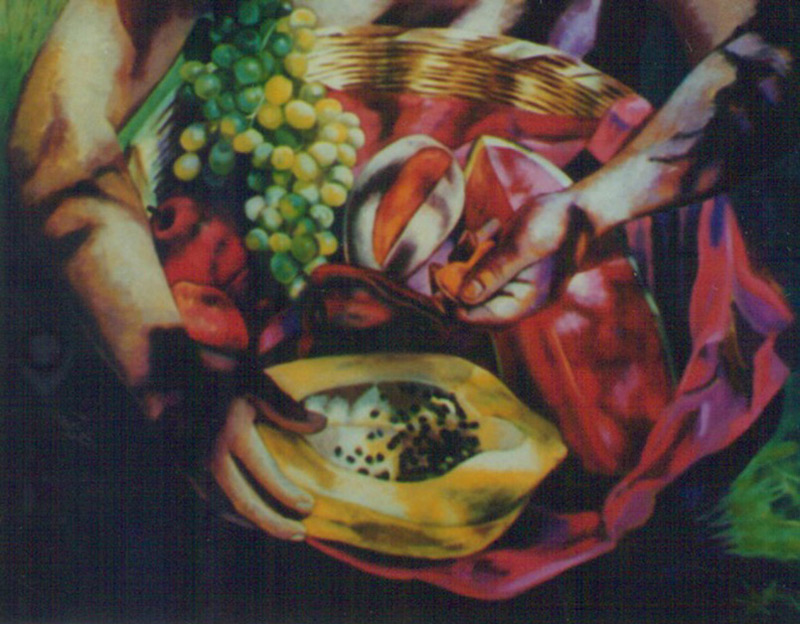

The intimate proximity offered to us, by the artist´s monumental approaches to the fruits, that expand and fill the hole of the canvas, express the admiration, surprise and pleasure of sexuality and fertility. The open fruits displaying their bones and the savory pulp around them, by showing their resemblance with female genitals, are both inviting and disturbing at the same time.

Quijano, being a feminist artist, gifted with a great sense of humor, in another set of still lifes reverts the metaphoric association of the fruits with female genitals and alludes, instead, to the masculine ones. Thus, in Mis frutas favoritas (My Favorite Fruits), Quijano portrays her own partner at that time, and when her sister asked her for a similar painting, Quijano gracefully painted the second work of the series, an allegorical portrait of her sister’s couple, entitling it this time, as Cada quien sus frutas (Each One Its Own Fruits).

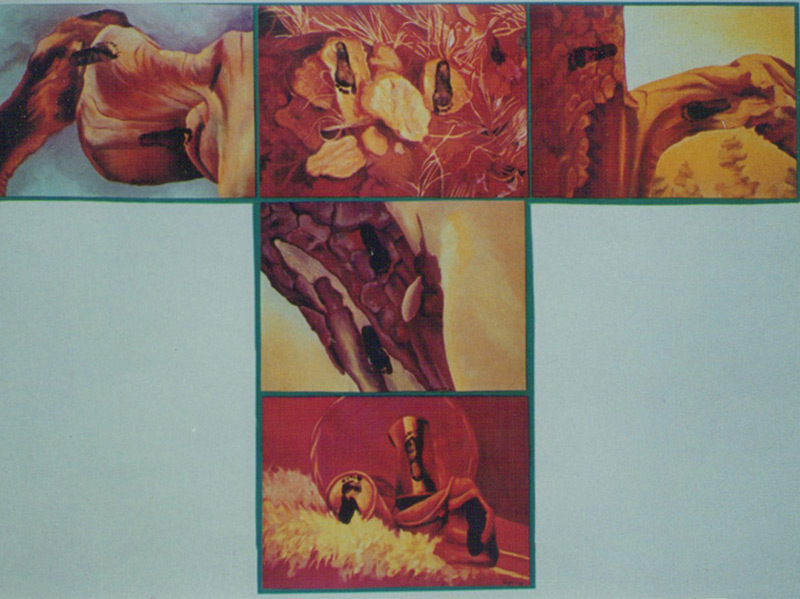

Quijano’s own feminist agenda is also evident in another series of allegorical still lifes, in which the artist denounces the social oppression committed against women. Her works mainly allude to the difficulties in rebelling and even talking, mainly when beauty standards and the willing to please others oppress our own lives, mostly by means of advertisements, becoming tyrants of our own lives. For Quijano, high heels are the main emblem of sex workers, a topic she raises her voice against in most of her works, like the ones exhibited here, which update the baroque genre of the vanitas concerning the passing of time, to the current reality of many women.

Finally, Quijano’s still lifes allow the artist to denounce the abuses humans have committed against nature itself. The painting Tu piel es mi piel (Your Skin is my Skin) is described by the artist as a visual poem intending to express that human beings must nourish with nature’s beauty. The poem-painting is built by several fragments: in the upper horizontal part, from left to right, “she”, “your prints on us” and “from the outside to the inside”; and in the vertical section, right after “your prints on us”, “he” and, finally, “our print on you”. By means of forms and colors that remind of some of her monumental fruits, trunks, footprints and garbage, Quijano contrasts the oceanic sentiment of union and respect for nature against pollution, which the current lack of ecological consciousness is generating, threatening life itself.

4. In Common: the Still lifes Infiltrate into Rina Lazo, Elena Climent and Patricia Quijano’s Murals

A different creative strategy shared by Rina Lazo, Elena Climent and Patricia Quijano in relation to still life production deals with the more or less textual paraphrases made by all three of them, with some of their own murals, thus demonstrating the fluidity that exists between domestic spaces, commonly associated with such artistic genre, and mural art, generally associated instead with the public.

Regarding Lazo, such translations can be seen especially in her mural Venerable abuelo maíz (Venerable Grandfather Corn) (1995), painted for the Mayan exhibition room of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, and the representation of corn, the tonacayotl or main nourishment of Mesoamerican cultures, in many of her easel still lifes, such as Mazorcas (Corncobs) (undated), Cosechando elotes (Harvesting Corns) (undated) and Ofrenda de mazorcas (Corncobs Offering) (2001).

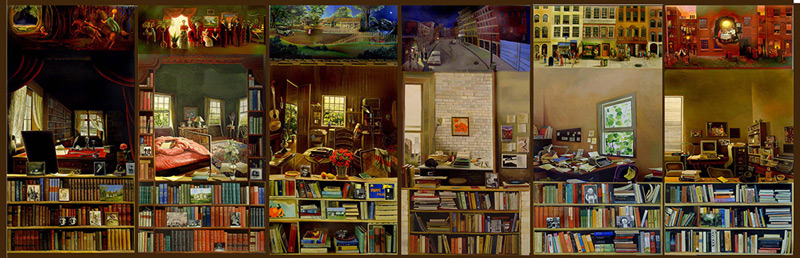

In Climent’s case, it is quite easy to see how in her mural, At Home With Their Books (En casa con sus libros) (2008), commissioned for a New York University’s building in Greenwich Village, New York, or in her work El papel de los libros o El milagro de la escritura (The Book’s Role or The Miracle of Writing), commissioned for the cinema’s yard of the José Vasconcelos Library in Mexico City, the artist follows the same topics and emotions found in her easel paintings.

After a careful research and a selection of the objects reflecting the presence of the different personalities in her murals, Climent elaborates and moves to mural painting with the same intention behind the offerings for the Day of the Dead, and by recreating the most intimate corners, she creates extremely touching expressions, especially when representing details of personal libraries, the objects compiled by their owners, and intimate photographs. They are ultimately allegorical portraits, made with still lifes, built with objects.

Quijano shows as well a deep unity in the representation of some of her main interests and concerns in both her easel painting and her mural works. Concerning still lifes, we must highlight Madona del delantal (Madonna With Apron) (1993-4) and Mi querida Contreras (My Dear Contreras) (1994), found inside market 384, also known as La Cruz in the Magdalena Contreras district, which takes still life genre to the walls because of the nature of the place as a market; and Luces cercenadas (Severed Lights) (2002), a transportable mural made as an homage for the murdered women in Ciudad Juárez which, because of its topic, its colors and style is closely linked to other works, such as Nunca más con tu voz (Nevermore With Your Voice) (2001).

Nevermore With Your Voice (the fighters series), 2001, mixed/canvas, 127 x 77 cm" />

Nevermore With Your Voice (the fighters series), 2001, mixed/canvas, 127 x 77 cm" />

In Conclusion, by Way of a Dessert…

Considering that just as we mentioned earlier, the still life´s genre has been traditionally and exclusively associated to interior domestic spaces, as the places of female identity par excellence; this original “new place” of the still lifes here studied, ranging from the house to the street, the private and the public, the individual and the collective, and the mundane and the sacred, is endowed with a very special symbolism, since it denotes the artists’ intention of surpassing the physical and spiritual isolation that women have been subject to through history in the closeness of the house, in order to integrating themselves in the cultural and public context at different levels.

Parting from the varied iconographic tradition of the still life as practiced in female Mexican painting throughout the 20th century, Rina Lazo, Elena Climent and Patricia Quijano transformed some of the traditional visual conventions of the genre and aimed to express new symbolic connotations, for they highlight women’s capacity of resistance, creativity and social roles played in history, showing at the same time that revolutions can also take place by subtly subverting some of the conventions associated to the most traditional artistic genres, instead of exclusively doing so by explicitly recurring to social and political subject matters.