In the vicinity of the woman and portrait photography (fragment)

Wednesday, 19 March 2014 18:42

Written by Eli Bartra

Lucero was born in Mexico City in 1947, a decade after the death of Baquedano, into an upper middle-class family. Her mother was a housewife, her father a medical epidemiologist. She had a son and a daughter, but by the time she began to devote herself professionally to photography in 1987, they were teenagers. She studied sociology and has been a feminist since the early 1970s.

One of Lucero’s specialties is portraits, although unlike Natalia Baquedano, she mainly photographs famous women, women who excel in something within the world of Mexican culture. She also produces men’s portraits, but to a much lesser extent. She began to explore this aspect at the end of the last decade as a result of her work in photojournalism. I think, however, that her inclination towards portraits of creative women also has to do with her feminism: she wants to show the existence, with names and faces, of women who have a major stake in the country's culture. She strives to provide a record of women’s work, for today and perhaps for the future. For the time when all that remains of these people is what they did and their faces, captured forever by Lucero’s lens.

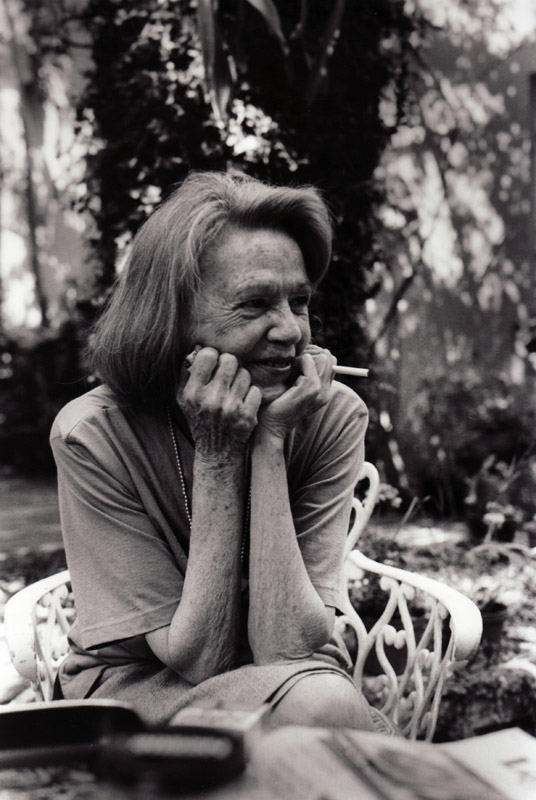

In her portraits of women, in each of her subjects, L. González detects a distinctive personality trait. To reveal this, she often uses objects or animals that make up the photographic context in which her “character” lives. These objects can be an apple, femur bones, a skull, cigarettes, a lighter, a piece of cloth... (PHOTO) Oddly enough, there is a slight similarity with the photographs of Baquedano, who also incorporates objects that animate her photos. The woman biting the apple, Ethel Krauze, is captured in an extremely spontaneous, slightly seductive gesture.

Her portraits are often not really strictly posed, although they seem to be. People do not usually pose for her; they are simply there and she takes the pictures. They are obviously aware of her presence with the camera, but if she can take them by surprise, she does. This is a crucial element for her. She actually produces two types of portrait: those she takes with an element of surprise and even if the person is aware that she is going to have her photo taken, she does not pose and is sometimes engaged doing something, (as in the portrait of Ethel Krauze). At other times, Lucero talks to her subject, telling her to move or pick up an object. For example, within this line, she has a kind of portrait like the one she did of Graciela Iturbide, which is very carefully thought out. It is constructed and extremely sophisticated. (Photo?). She portrayed her as a soul in purgatory: she has her eyes closed and on her chest, she has a piece of cardboard with painted flames in the foreground. She also incorporated porcelain hands belonging to one of Graciela’s collections. Perhaps the fact that Graciela Iturbide is a photographer forced Lucero to take a more carefully thought out photograph, obliging her to construct something rather than leaving it to chance. I imagine it must have been challenge to photograph a good photographer.

Lucero finds it easier to photograph women because she establishes a much more direct relationship with them than with men. She feels more comfortable because she has more permissibility; apparently, she does not censor herself with women. When she makes them pose, she can ask them to lower one shoulder, or sit in a certain way. With men, she keeps her distance because she does not want them to think that she is seducing or flirting with them.

She used a manual Niko FM camera and three lenses-wide angle, normal and telephoto. She never uses flash. She forces the film if necessary, which is why some of her photos have a grainy texture. She prefers to use an asa 400 in low light. In other words, she uses technique, but with the least possible artifice; she does not produce studio portraits. In most of them, she uses natural light and occasionally, light bulbs. So her photos nearly always have a sharp contrast. She likes to have control over the camera, so she uses manual rather than automatic settings, which enables her to achieve the atmosphere and texture she seeks. For her portraits of creators, she uses black and white film. However, when she travels and photographs otherness, such as women on the Pacific coast, for example, she uses color film.

It is as though she wishes to capture those alien realities just as they are, with all their colors. Maybe this is the way she has chosen to discover and convey different settings and the identity of others who are different from her, and quite distinct from her city and her environment.

In her portraits, the background is entirely circumstantial. She likes facial expressions, particularly the eyes and mouth. The hands are also very important. The face is the window for getting to know a person. The rest is merely adornment. Often there is no background and when there is, it may be because she was not sufficiently interested in the subject. Or perhaps because she was unable to reveal the personality of the subject as she wishedwith the face and hands alone.

For Lucero, portraits are a way of getting to know the people she photographs better, who are usually people she likes. Publishing her work is a way of showing who she is; she reveals herself through the portraits of others.

She tends to produce portraits of the face alone, medium shots, unlike Baquedano who preferred the full-length portrait, general shots. This is perhaps why Lucero’s photos are usually very powerful. That is their main feature: strength. Within a short time, Lucero Gonzalez has managed to “tame” the lens to suit her desires. And one can say that she wishes to show, and I think she achieves this, the strength and dignity of women.

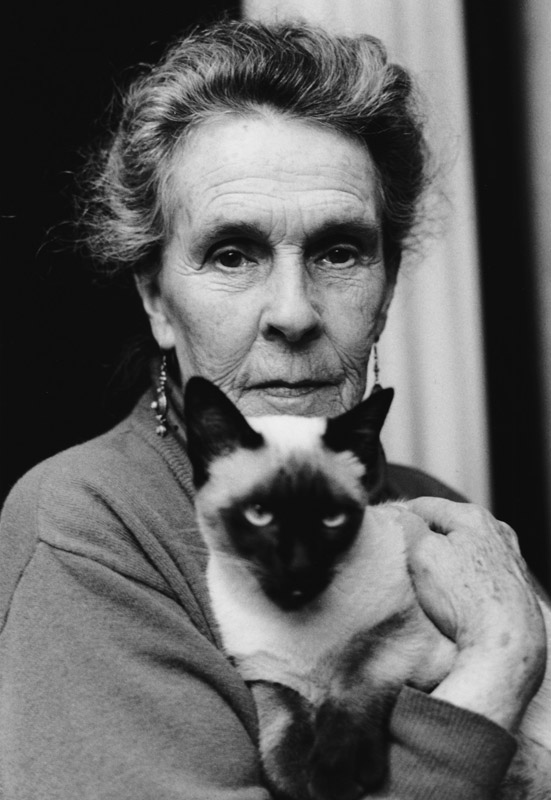

In the (PHOTO) we see the portrait of the English-Mexican painter Leonora Carrington, which emphasizes her strength, her rather feline energy through the incorporation of a cat into the photo. Leonora and the cat staring at the camera, challenging it. Two soul mates bound by the action of the lens that form a unit. This photograph could be called Leonora-cat.

Another aspect of Lucero’s portraiture is nude photography and within it, the male nude. It is, I believe, another expression of the rebellion against the limits still imposed, however subtly, by the dominant morals about what “real” women should or should not do. Even today at the end of the millennium, a female photographer taking shots of male nudes is still regarded as irreverent. There have been very few in the history of women’s photography. Let us recall, however, the beautiful male nude by Imogen Cunningham.

There is no doubt that Lucero absolutely prefers photographing women. She likes women’s bodies better than men’s, she thinks they have more possibilities because men’s are very rigid. To photography male nudes, she needs the person to be very close, which is why her first “model” was her partner and her second her son. She feels much more relaxed with women. She communicates with them more easily and understands their moods and moments better.

Although she has “specialized” in photographing female creators, she says that she is equally at ease creating a portrait of a well-known or even famous woman as she is when photographing a woman of the people, an “ordinary woman.” In her attempt to discover a person’s essence through photography, she does exactly the same. She tries to perceive, feel and sense who the person in front of her is, whether it is the writer Ángeles Mastretta, or Gilberta, a woman from the coast.

Lucero is now exploring a different form of portrait, which for her are constructed portraits. For example, she has a series representing the Nahuatl goddess Xochiquetzal (feathered flower), whom she regards as a Venus as the goddess of love and sensuality, hence the semi-nude photograph. And in this case, she does consider the background.

She also constructs the context, with hearts, with the walls of the ruins of Xochicalco, with blood... information that helps to express what she wants to say about these portraits based on mythological characters.

She also has a series on girls and adolescents from the coasts of Oaxaca and Guerrero. Most of them sell bread, fruit, tomatoes and many other items. They are all color photographs and distinct from those of women creators, because they all have a quite distinct context. Here the background is as important as the faces and hands.

There is an interesting parallel between the photography of Natalia Baquedano and Lucero González which is the fact that both tend to photograph women. Both of them, whether consciously or unconsciously, provide us with an image of women as whole persons. They do so in different ways, Baquedano showing action and dynamism and even insinuating the mutilation of women as a result of motherhood in the photo. Conversely, Lucero González photographs the creative women of Mexico with strength and determination.

Lucero was born in Mexico City in 1947, a decade after the death of Baquedano, into an upper middle-class family. Her mother was a housewife, her father a medical epidemiologist. She had a son and a daughter, but by the time she began to devote herself professionally to photography in 1987, they were teenagers. She studied sociology and has been a feminist since the early 1970s.

One of Lucero’s specialties is portraits, although unlike Natalia Baquedano, she mainly photographs famous women, women who excel in something within the world of Mexican culture. She also produces men’s portraits, but to a much lesser extent. She began to explore this aspect at the end of the last decade as a result of her work in photojournalism. I think, however, that her inclination towards portraits of creative women also has to do with her feminism: she wants to show the existence, with names and faces, of women who have a major stake in the country's culture. She strives to provide a record of women’s work, for today and perhaps for the future. For the time when all that remains of these people is what they did and their faces, captured forever by Lucero’s lens.

In her portraits of women, in each of her subjects, L. González detects a distinctive personality trait. To reveal this, she often uses objects or animals that make up the photographic context in which her “character” lives. These objects can be an apple, femur bones, a skull, cigarettes, a lighter, a piece of cloth... (PHOTO) Oddly enough, there is a slight similarity with the photographs of Baquedano, who also incorporates objects that animate her photos. The woman biting the apple, Ethel Krauze, is captured in an extremely spontaneous, slightly seductive gesture.

Her portraits are often not really strictly posed, although they seem to be. People do not usually pose for her; they are simply there and she takes the pictures. They are obviously aware of her presence with the camera, but if she can take them by surprise, she does. This is a crucial element for her. She actually produces two types of portrait: those she takes with an element of surprise and even if the person is aware that she is going to have her photo taken, she does not pose and is sometimes engaged doing something, (as in the portrait of Ethel Krauze). At other times, Lucero talks to her subject, telling her to move or pick up an object. For example, within this line, she has a kind of portrait like the one she did of Graciela Iturbide, which is very carefully thought out. It is constructed and extremely sophisticated. (Photo?). She portrayed her as a soul in purgatory: she has her eyes closed and on her chest, she has a piece of cardboard with painted flames in the foreground. She also incorporated porcelain hands belonging to one of Graciela’s collections. Perhaps the fact that Graciela Iturbide is a photographer forced Lucero to take a more carefully thought out photograph, obliging her to construct something rather than leaving it to chance. I imagine it must have been challenge to photograph a good photographer.

Lucero finds it easier to photograph women because she establishes a much more direct relationship with them than with men. She feels more comfortable because she has more permissibility; apparently, she does not censor herself with women. When she makes them pose, she can ask them to lower one shoulder, or sit in a certain way. With men, she keeps her distance because she does not want them to think that she is seducing or flirting with them.

She used a manual Niko FM camera and three lenses-wide angle, normal and telephoto. She never uses flash. She forces the film if necessary, which is why some of her photos have a grainy texture. She prefers to use an asa 400 in low light. In other words, she uses technique, but with the least possible artifice; she does not produce studio portraits. In most of them, she uses natural light and occasionally, light bulbs. So her photos nearly always have a sharp contrast. She likes to have control over the camera, so she uses manual rather than automatic settings, which enables her to achieve the atmosphere and texture she seeks. For her portraits of creators, she uses black and white film. However, when she travels and photographs otherness, such as women on the Pacific coast, for example, she uses color film.

It is as though she wishes to capture those alien realities just as they are, with all their colors. Maybe this is the way she has chosen to discover and convey different settings and the identity of others who are different from her, and quite distinct from her city and her environment.

In her portraits, the background is entirely circumstantial. She likes facial expressions, particularly the eyes and mouth. The hands are also very important. The face is the window for getting to know a person. The rest is merely adornment. Often there is no background and when there is, it may be because she was not sufficiently interested in the subject. Or perhaps because she was unable to reveal the personality of the subject as she wishedwith the face and hands alone.

For Lucero, portraits are a way of getting to know the people she photographs better, who are usually people she likes. Publishing her work is a way of showing who she is; she reveals herself through the portraits of others.

She tends to produce portraits of the face alone, medium shots, unlike Baquedano who preferred the full-length portrait, general shots. This is perhaps why Lucero’s photos are usually very powerful. That is their main feature: strength. Within a short time, Lucero Gonzalez has managed to “tame” the lens to suit her desires. And one can say that she wishes to show, and I think she achieves this, the strength and dignity of women.

In the (PHOTO) we see the portrait of the English-Mexican painter Leonora Carrington, which emphasizes her strength, her rather feline energy through the incorporation of a cat into the photo. Leonora and the cat staring at the camera, challenging it. Two soul mates bound by the action of the lens that form a unit. This photograph could be called Leonora-cat.

Another aspect of Lucero’s portraiture is nude photography and within it, the male nude. It is, I believe, another expression of the rebellion against the limits still imposed, however subtly, by the dominant morals about what “real” women should or should not do. Even today at the end of the millennium, a female photographer taking shots of male nudes is still regarded as irreverent. There have been very few in the history of women’s photography. Let us recall, however, the beautiful male nude by Imogen Cunningham.

There is no doubt that Lucero absolutely prefers photographing women. She likes women’s bodies better than men’s, she thinks they have more possibilities because men’s are very rigid. To photography male nudes, she needs the person to be very close, which is why her first “model” was her partner and her second her son. She feels much more relaxed with women. She communicates with them more easily and understands their moods and moments better.

Although she has “specialized” in photographing female creators, she says that she is equally at ease creating a portrait of a well-known or even famous woman as she is when photographing a woman of the people, an “ordinary woman.” In her attempt to discover a person’s essence through photography, she does exactly the same. She tries to perceive, feel and sense who the person in front of her is, whether it is the writer Ángeles Mastretta, or Gilberta, a woman from the coast.

Lucero is now exploring a different form of portrait, which for her are constructed portraits. For example, she has a series representing the Nahuatl goddess Xochiquetzal (feathered flower), whom she regards as a Venus as the goddess of love and sensuality, hence the semi-nude photograph. And in this case, she does consider the background.

She also constructs the context, with hearts, with the walls of the ruins of Xochicalco, with blood... information that helps to express what she wants to say about these portraits based on mythological characters.

She also has a series on girls and adolescents from the coasts of Oaxaca and Guerrero. Most of them sell bread, fruit, tomatoes and many other items. They are all color photographs and distinct from those of women creators, because they all have a quite distinct context. Here the background is as important as the faces and hands.

There is an interesting parallel between the photography of Natalia Baquedano and Lucero González which is the fact that both tend to photograph women. Both of them, whether consciously or unconsciously, provide us with an image of women as whole persons. They do so in different ways, Baquedano showing action and dynamism and even insinuating the mutilation of women as a result of motherhood in the photo. Conversely, Lucero González photographs the creative women of Mexico with strength and determination.