Bustle and nostalgia

Friday, 04 April 2014 12:05

Written by Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo AC

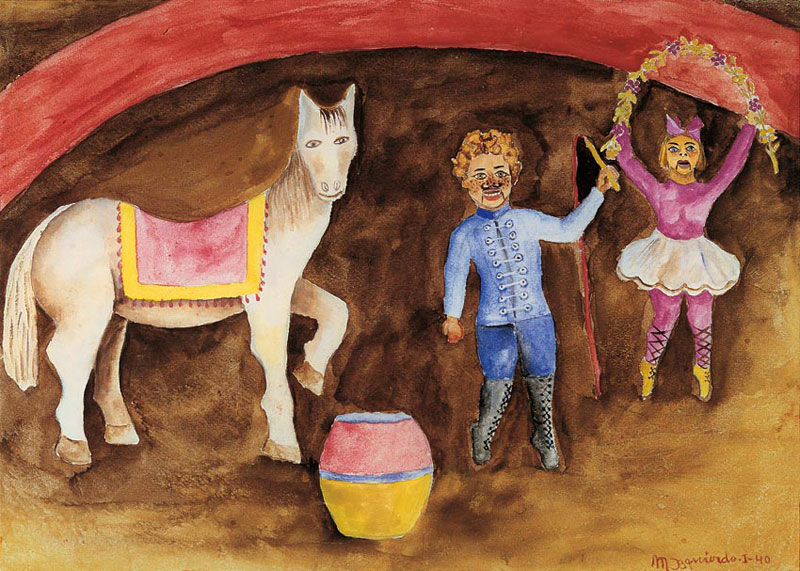

Izquierdo was bewitched by horses and the circus. She escaped unharmed after being knocked over by a herd of wild animals, and was lost for 24 hours with a wandering circus when she was just two. These events featured among the dreams and painting of María Izquierdo (1902-1955), yet in her art she does not merely derive an overflowing, vigorous, popular Mexicanness from these anecdotes, as is often believed. She painted that which was close to her, but did so in a more complete, complex manner, using a language full of visual metaphors of sordidness and pain, with a longing for a lost innocence.

The specialist Oliver Debroise has referred to these elements with a less cheerful content, which complement the contributions of this artist from Jalisco, the 50th anniversary of whose death is celebrated on December 3. A creator who not only brought joy to Mexico’s bohemian lifestyle of the first half of the 20th century, but also developed in her work “a sophisticated expressionism that demonstrates, beyond conventions, total creative freedom”. (Debroise)

María Cenobia Izquierdo Gutiérrez was born in San Juan de los Lagos, and lived with her grandparents in this part of Jalisco from a young age. She then traveled with her parents to Aguascalientes and later lived with her mother in Torreón and Saltillo. Her life followed the rhythm of 6 am mass, until she was married to a soldier at the age of 14.

Her provincial, humdrum life with three children changed when the family moved to Mexico City in 1923 and she enrolled at the Secretary of Public Education’s Painting and Sculpture Academy. There, she was taught by Germán Gedovius but disliked the routine and so she worked at home. At this time, Diego Rivera, the director of the former Academy, praised her painting, which led to her rejection by many students, who considered her work “stupid”.

This had no bearing on the budding artist, who continued to paint to express her creative and vital independence. Izquierdo separated from her husband, thrived in the bohemian atmosphere of the era and became romantically involved with the painter Rufino Tamayo. There was a clear influence between the two in pictorial subjects and composition, and together they became acquainted with the intellectual sphere surrounding the magazine Contemporáneos.

Her first exhibitions were held in Mexico and the United States, but heart disease drew her away from her workshop and she had to give painting classes to support her children and the parties at her home and the Leda cabaret.

Izquierdo’s life and work was then marked by a second relationship. Raúl Uribe, an untalented Chilean painter exerted an influence over her paintings, which then consisted principally in portraits and still lifes, and encouraged a less imaginative and fresh vision, according to the specialist Sylvia Navarrete. However, towards the second half of the 1940s, her creativity reemerged in urban and rural landscapes teeming with fish, snails, solitary horses, cupboards and mysterious self-portraits.

After contributing to the magazine Hoy to argue against the muralists, then popular with galleries, and express her preference for figurative painting, Izquierdo displayed her work in and outside Mexico, journeying through Peru and Chile (where she married Uribe), enjoying success with critics and the public, before returning to her homeland, where her mural for the Mexico City Palace was rejected. Diego Rivera and Siqueiros considered that their colleague did not have sufficient experience in painting fresco, and it was left as an unfinished project.

Overcoming the disappointment, Izquierdo continued to incorporate various objects from her surroundings into her mysterious world: toys, candy, child mythology, loves. During this period, she lived with doves, dogs, a chicken, a parrot and a monkey, and dressed in petticoats and lace. Paralyzed down her right side for eight months by a hemiplegia, she subsequently suffered two embolisms and a difficult recovery before resuming her painting. She divorced Uribe, then a fourth embolism prevented her from attending the Homage organized by the National Institute of Fine Art (INBA), which was inaugurated eight months after her death at 53. These 75 paintings revealed the universe of dreams, mystery, longing, play, circus and pain of one of Mexico’s leading artists, still held in great esteem today.

(*) Quotes and information from the book María Izquierdo. Cultural Center of Contemporary Art AC, 1988. This text was published in the column Mujeres Insumisas (Insubordinate Women) of La Jornada Semanal (December 31 2005)??

Izquierdo was bewitched by horses and the circus. She escaped unharmed after being knocked over by a herd of wild animals, and was lost for 24 hours with a wandering circus when she was just two. These events featured among the dreams and painting of María Izquierdo (1902-1955), yet in her art she does not merely derive an overflowing, vigorous, popular Mexicanness from these anecdotes, as is often believed. She painted that which was close to her, but did so in a more complete, complex manner, using a language full of visual metaphors of sordidness and pain, with a longing for a lost innocence.

The specialist Oliver Debroise has referred to these elements with a less cheerful content, which complement the contributions of this artist from Jalisco, the 50th anniversary of whose death is celebrated on December 3. A creator who not only brought joy to Mexico’s bohemian lifestyle of the first half of the 20th century, but also developed in her work “a sophisticated expressionism that demonstrates, beyond conventions, total creative freedom”. (Debroise)

María Cenobia Izquierdo Gutiérrez was born in San Juan de los Lagos, and lived with her grandparents in this part of Jalisco from a young age. She then traveled with her parents to Aguascalientes and later lived with her mother in Torreón and Saltillo. Her life followed the rhythm of 6 am mass, until she was married to a soldier at the age of 14.

Her provincial, humdrum life with three children changed when the family moved to Mexico City in 1923 and she enrolled at the Secretary of Public Education’s Painting and Sculpture Academy. There, she was taught by Germán Gedovius but disliked the routine and so she worked at home. At this time, Diego Rivera, the director of the former Academy, praised her painting, which led to her rejection by many students, who considered her work “stupid”.

This had no bearing on the budding artist, who continued to paint to express her creative and vital independence. Izquierdo separated from her husband, thrived in the bohemian atmosphere of the era and became romantically involved with the painter Rufino Tamayo. There was a clear influence between the two in pictorial subjects and composition, and together they became acquainted with the intellectual sphere surrounding the magazine Contemporáneos.

Her first exhibitions were held in Mexico and the United States, but heart disease drew her away from her workshop and she had to give painting classes to support her children and the parties at her home and the Leda cabaret.

Izquierdo’s life and work was then marked by a second relationship. Raúl Uribe, an untalented Chilean painter exerted an influence over her paintings, which then consisted principally in portraits and still lifes, and encouraged a less imaginative and fresh vision, according to the specialist Sylvia Navarrete. However, towards the second half of the 1940s, her creativity reemerged in urban and rural landscapes teeming with fish, snails, solitary horses, cupboards and mysterious self-portraits.

After contributing to the magazine Hoy to argue against the muralists, then popular with galleries, and express her preference for figurative painting, Izquierdo displayed her work in and outside Mexico, journeying through Peru and Chile (where she married Uribe), enjoying success with critics and the public, before returning to her homeland, where her mural for the Mexico City Palace was rejected. Diego Rivera and Siqueiros considered that their colleague did not have sufficient experience in painting fresco, and it was left as an unfinished project.

Overcoming the disappointment, Izquierdo continued to incorporate various objects from her surroundings into her mysterious world: toys, candy, child mythology, loves. During this period, she lived with doves, dogs, a chicken, a parrot and a monkey, and dressed in petticoats and lace. Paralyzed down her right side for eight months by a hemiplegia, she subsequently suffered two embolisms and a difficult recovery before resuming her painting. She divorced Uribe, then a fourth embolism prevented her from attending the Homage organized by the National Institute of Fine Art (INBA), which was inaugurated eight months after her death at 53. These 75 paintings revealed the universe of dreams, mystery, longing, play, circus and pain of one of Mexico’s leading artists, still held in great esteem today.

(*) Quotes and information from the book María Izquierdo. Cultural Center of Contemporary Art AC, 1988. This text was published in the column Mujeres Insumisas (Insubordinate Women) of La Jornada Semanal (December 31 2005)??