Helen Escobedo, a vision making unexpected leaps forward

Thursday, 29 May 2014 14:24

Written by Merry McMasters for the newspaper La Jornada.

The sculptor Helen Escobedo (Mexico City, 1934) could have been a violinist or a dancer, however modeling clay was the activity that she enjoyed most.

This innate talent, discovered by an English mother who always channeled her towards art, led to her receiving the National Arts Prize in 2009 in the Fine Art category, which she shared with the composer Arturo Márquez.

Once her hearing improved, Escobedo’s mother sent her to a drawing teacher. "We would wander over the old bridges of the San Ángel river, drawing trees and landscapes.

“Later, by chance, I enrolled in Mexico City College and found myself taught by Germán Cueto, who immediately realized that I had no right to be there as I was only 15. Nevertheless, I remained there for a year.”

A vision making unexpected leaps forward.

“Then,” says Escobedo, “by good fortune, John Skipping, a renowned sculpture teacher from the Royal College of Art in London, visited my house, and my mother told him that she would be delighted to show him her daughter’s little studio in the washroom. Skipping came to see me and we talked for about two hours about alternative techniques. He said that he would come back from Oaxaca two months later to see what I had produced.”

“Two months later, I had filled the whole washroom with new figures using his techniques. He was impressed and said: “’I do not want your talent to go to waste. I will arrange for a scholarship for you to spend a year at the Royal College. If you reach the required level they will award you a three-year scholarship.”

“I went and passed the first year exam, at which one of the judges was Henry Moore. They eventually gave me a full scholarship. Back then I was too young, the Royal College being a postgraduate establishment, and I enrolled when I was 16.”

Escobedo’s first sculptures were from bronze, but she became tired of the material after her fifth exhibition. She continued to create what the art critic Raquel Tibol called her “dynamic walls,” large colored panels between a door and a window, with a more architectural quality. “It was closer to design, but I was fascinated by the human dimension, which went beyond my little bronze figures.”

Escobedo says that every three, four or five years she would throw herself into something new. “When I had finished with one style of language I wanted to start something new. All my life I have made unexpected leaps forward, and my classmates would say: “’Helen, keep still! Why don’t you stay on the same track?’” She eventually devoted herself to in situ installations.

Inés Amor, her gallery owner in Mexico, asked her to continue making bronze sculptures, as her last exhibition has been very well received. However, Escobedo explains that the subject of the exhibition was the artist and their audience: “The artist was the central being, gradually surrounded by an audience, which enabled her to grow until she towered over them. She felt like a prisoner, so she broke out of this fence of admirers, moved away and was left alone. This happened to me several times, but it never worried me.”

“As a matter of fact, my main source of concern was paying the rent for my studio in San Ángel, which belonged to the muralist David Siqueiros, and so I accepted the post of head of art department at the University Museum of Science and Art at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. I had already directed a museum. I would even have agreed to be a violinist in the Mexican Symphonic Orchestra, as I needed that money and did not want to ask my father for it.”

Pathways ahead.

Escobedo is still a bold artist, and realizes that there are still many unexplored paths before her. “Now that this world is more accessible, and arts mingle and fuse, one can do so much. For example, I never attempted video, or electric devices. It would be interesting to work with Alejandro Luna and a young composer when we create one of the areas in the new Museum of Tolerance.”

Are you used to your work being a source of controversy?

When you produce an installation somewhere where nobody expects it, that attracts controversy. I do aim to provoke, but not in a negative sense.

During a career that has spanned half a century, which direction has art taken?

Many pathways have been taken, and there are many that still lie ahead. Now it is harder to discern between artists (arguably thanks to globalization), as they are all invited to biennials everywhere. In this digital era, one can be instantly well known.

Today Helen Escobedo, a tireless traveler who has taken her artwork to countless locations abroad, will be awarded the recognition of distinguished citizen by Marcelo Ebrard, Head of the Government of Mexico City, at the Former Town Hall.

The sculptor Helen Escobedo (Mexico City, 1934) could have been a violinist or a dancer, however modeling clay was the activity that she enjoyed most.

As a young child she created cruel, ferocious animals, and imagined that they stung her ears at night, causing her a great deal of pain.

This innate talent, discovered by an English mother who always channeled her towards art, led to her receiving the National Arts Prize in 2009 in the Fine Art category, which she shared with the composer Arturo Márquez.

Once her hearing improved, Escobedo’s mother sent her to a drawing teacher. "We would wander over the old bridges of the San Ángel river, drawing trees and landscapes.

“Later, by chance, I enrolled in Mexico City College and found myself taught by Germán Cueto, who immediately realized that I had no right to be there as I was only 15. Nevertheless, I remained there for a year.”

A vision making unexpected leaps forward.

“Then,” says Escobedo, “by good fortune, John Skipping, a renowned sculpture teacher from the Royal College of Art in London, visited my house, and my mother told him that she would be delighted to show him her daughter’s little studio in the washroom. Skipping came to see me and we talked for about two hours about alternative techniques. He said that he would come back from Oaxaca two months later to see what I had produced.”

“Two months later, I had filled the whole washroom with new figures using his techniques. He was impressed and said: “’I do not want your talent to go to waste. I will arrange for a scholarship for you to spend a year at the Royal College. If you reach the required level they will award you a three-year scholarship.”

“I went and passed the first year exam, at which one of the judges was Henry Moore. They eventually gave me a full scholarship. Back then I was too young, the Royal College being a postgraduate establishment, and I enrolled when I was 16.”

Escobedo’s first sculptures were from bronze, but she became tired of the material after her fifth exhibition. She continued to create what the art critic Raquel Tibol called her “dynamic walls,” large colored panels between a door and a window, with a more architectural quality. “It was closer to design, but I was fascinated by the human dimension, which went beyond my little bronze figures.”

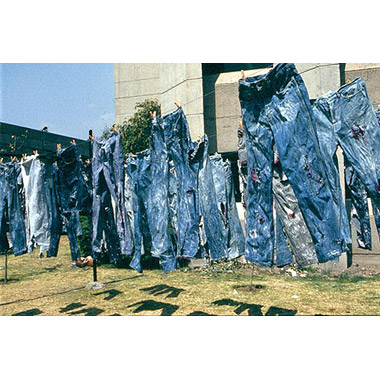

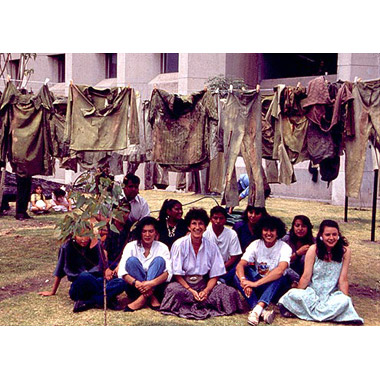

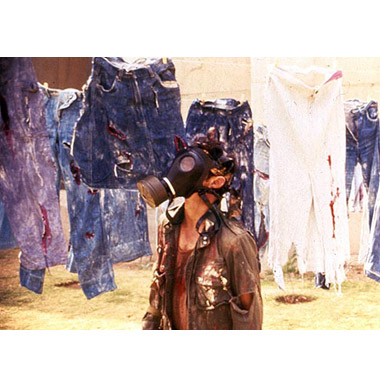

Escobedo says that every three, four or five years she would throw herself into something new. “When I had finished with one style of language I wanted to start something new. All my life I have made unexpected leaps forward, and my classmates would say: “’Helen, keep still! Why don’t you stay on the same track?’” She eventually devoted herself to in situ installations.

Inés Amor, her gallery owner in Mexico, asked her to continue making bronze sculptures, as her last exhibition has been very well received. However, Escobedo explains that the subject of the exhibition was the artist and their audience: “The artist was the central being, gradually surrounded by an audience, which enabled her to grow until she towered over them. She felt like a prisoner, so she broke out of this fence of admirers, moved away and was left alone. This happened to me several times, but it never worried me.”

“As a matter of fact, my main source of concern was paying the rent for my studio in San Ángel, which belonged to the muralist David Siqueiros, and so I accepted the post of head of art department at the University Museum of Science and Art at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. I had already directed a museum. I would even have agreed to be a violinist in the Mexican Symphonic Orchestra, as I needed that money and did not want to ask my father for it.”

Pathways ahead.

Escobedo is still a bold artist, and realizes that there are still many unexplored paths before her. “Now that this world is more accessible, and arts mingle and fuse, one can do so much. For example, I never attempted video, or electric devices. It would be interesting to work with Alejandro Luna and a young composer when we create one of the areas in the new Museum of Tolerance.”

Are you used to your work being a source of controversy?

When you produce an installation somewhere where nobody expects it, that attracts controversy. I do aim to provoke, but not in a negative sense.

During a career that has spanned half a century, which direction has art taken?

Many pathways have been taken, and there are many that still lie ahead. Now it is harder to discern between artists (arguably thanks to globalization), as they are all invited to biennials everywhere. In this digital era, one can be instantly well known.

Today Helen Escobedo, a tireless traveler who has taken her artwork to countless locations abroad, will be awarded the recognition of distinguished citizen by Marcelo Ebrard, Head of the Government of Mexico City, at the Former Town Hall.