Strip away all that you have learnt… and fly

One of Yampolsky’s most defining characteristics is her respect for people, Nature and objects. Everything that surrounds her deserves attention and inspires her to think, and she captures it with her camera, to release it in images. At 76, Mariana Yampolsky still continues asking questions, and prefers to question any answer. Does the photographer seek beauty? Is a photograph art or a document? Can the photographer cease to intrude?

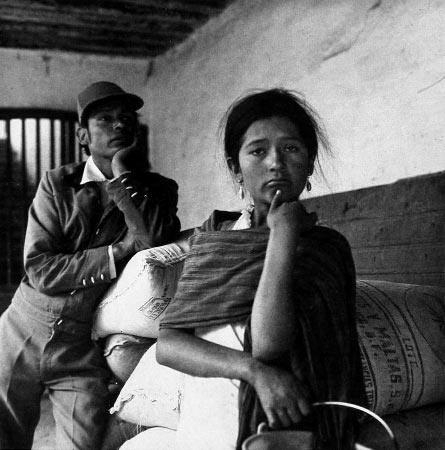

Yampolsky is a small, pale woman with curly, silvery hair and an easy smile. But her expression immediately turns grave when she speaks of the poverty and inequality suffered by many in the Mexican countryside. Yampolsky has depicted these villages throughout the country since she arrived in Mexico in 1944, attracted by the images and history described by John Steinbeck in The Forgotten Village. “Since I was young, Mexico has been a deeply enchanting, attractive country, because of the importance of the Mexican Revolution. Since my very first days here, I wanted to be part of it and face the good, the bad and the ugly.”

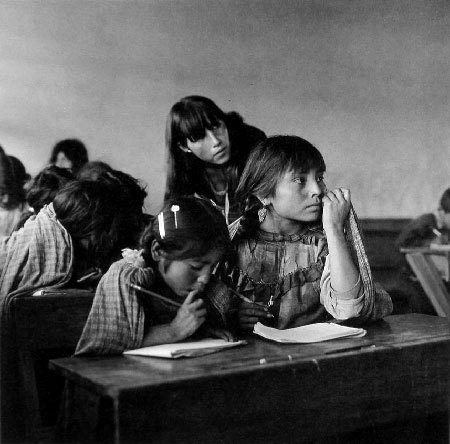

And so it was, and Yampolsky threw herself entirely into this new environment. Born in Chicago, Illinois, and having studied Humanities at the University of Chicago, she became a Mexican citizen and produced work that positioned her as a key photographer. Indeed, without any fuss, far from the spotlight, she has put together a vast archive of over 30,000 negatives, which she will donate to the Photographic Library of the National Institute of Art and History in Pachuca. These include series on popular art, vernacular architecture, Mazahua and Otomí communities, couples in Oaxaca, Puebla and Tlaxcala and huts and palm trees in Tlacotalpan.

“I was trained in Humanities, which gave me an understanding of people. I like to think that with my photos I show the human side of those who have no voice in the economy, politics and culture.”

Having just settled in Mexico, Yampolsky did not immediately work in photography. She crossed the border to find the “Taller de Gráfica Popular” and become the first woman to join the collective of etchers with a political and social leaning. However, she was also interested in painting, and enrolled at La Esmeralda Art School. There, among plaques and stretcher frames, she met a woman who marked her life: Dolores Álvarez Bravo. At the Academy of San Carlos she began to take photography classes with her, became her assistant and she has never abandoned her profession or her universe depicted in black and white.

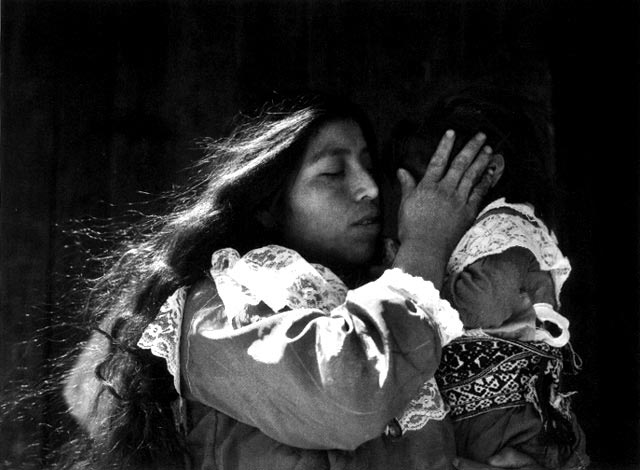

From Álvarez she learned that being a woman is not an obstacle to producing photographs, and to appreciate the subjects’ dignity and avoid being invasive. “That was a great problem with my profession. One of the photographer’s task is to dig deep into their emotions or reason for existence, to reach the interior of the subject. My work has always involved a certain modesty, and I avoided using my camera when it invades privacy.

Her focus is not merely the face of children and elderly persons. She also depicts their huts, work tools, courtyards and kitchens. There are not only strong aesthetic qualities in her simple, clean yet calm images; they also carry strong ethics. Indeed, each photo, in which the artist spreads wide her wings, shows respect for human dignity.

Mariana Yampolsky passed away on May 3, 2002. Text originally published in La Jornada Semanal (February 17 2002), part of a book edited by the Autonomous University of Nuevo León (UANL).