You are searching still, searching for a place for us

Tuesday, 27 November 2018 14:56

Written by Mónica Castillo

What happens when a daughter loses her mother? What actions and rituals will occupy an inquiry that the daughter knows in advance will receive no response?

When an artist loses her mother, she inherits a privileged legacy: the objects that accompanied her. Knowing that the relevance of this raw material is not its form, how it was made, or even its physical existence, the daughter becomes someone else when she returns to these objects with a creative agenda.

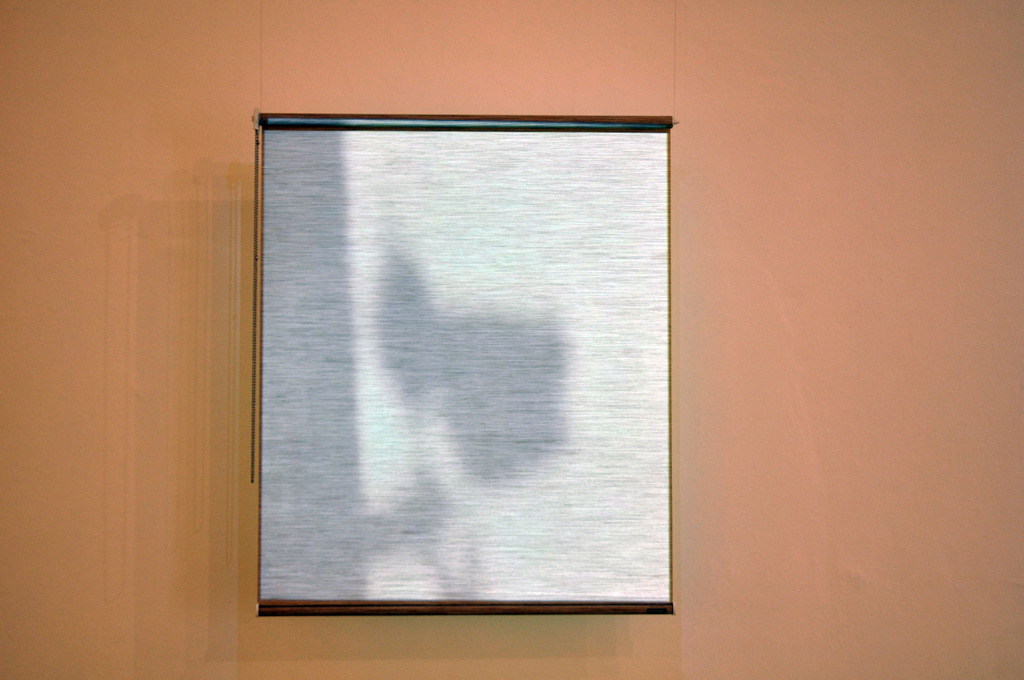

Then the artist establishes a contract. She reproduces favorite photos, selects fragments of them and reproduces them as ghostly images. Placed in the location where they lived on the shelves in the family room, the images appear even further away in time. More so than the photos themselves. She takes old plans of the family house and converts them into large inflatable objects. They are no longer the dream of a future space for all, but have been converted into split skins of objects that the daughter knows were precious to her mother. Like an archeologist in her childhood home, she rescues precise shadows, but not just any shadows, precisely those that were reflected in the blinds of her mother’s bedroom.

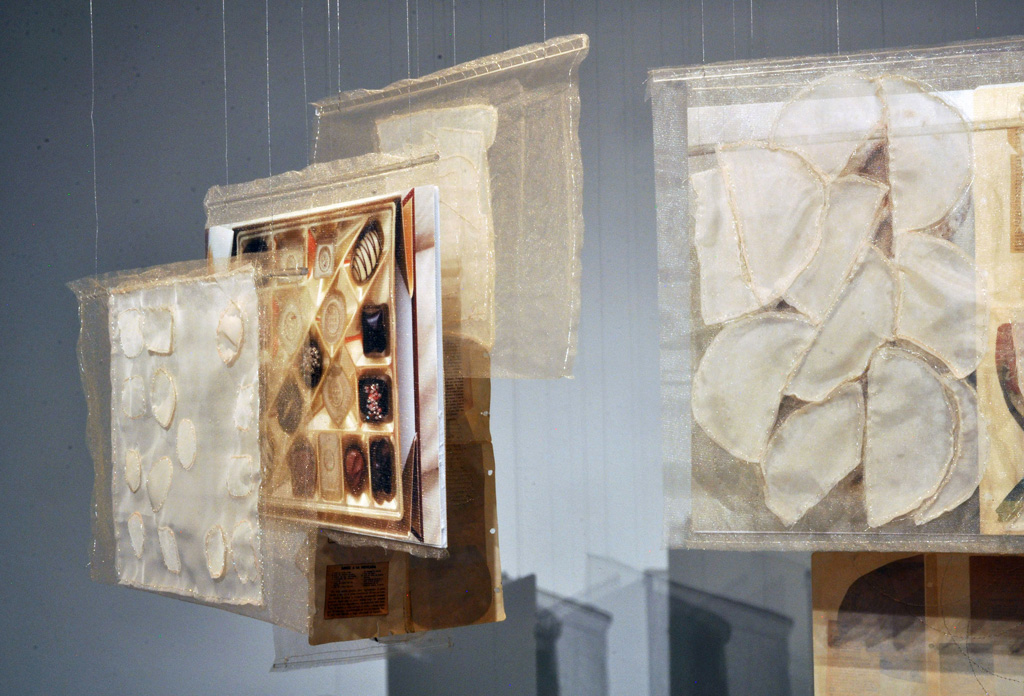

The central piece on display is the table where the family gathered. Over it, dangle images of the mother’s old cookbooks, of the dishes she prepared and the edible gifts she was lovingly offered at the end. The artist interposes metallic thread and beads among the images. She imagines herself treasuring these memories when she captures the reflected light, when she passes time with what are now objects, but once were a promise of life, of reciprocity. This cycle is affirmed by the oval shape of the table. With the help of these objects and actions, it is impossible not to return to the flow of giving that simultaneously nurtures, seals affections and creates daily memory. To furnish and inhabit the circle of gifts in order to keep it alive and not forget.

Finally, contradictorily, these gestures do not create meaning in themselves. It is impossible to separate them from the mother’s presence, because she was the first choreographer of what are now leftover scraps. It is the right and privilege of the daughter in mourning to decide what will last in memory, her memory. She can rescue, choose, pay attention, invest time in a legacy and thus re-acquaint herself with it. But it is the absence of the mother through “that tenuous fluid that must be protected forever,”* that not only initiates the creation, but makes it into an offering.

(*Henri Michaux, “We two, still.”)

When an artist loses her mother, she inherits a privileged legacy: the objects that accompanied her. Knowing that the relevance of this raw material is not its form, how it was made, or even its physical existence, the daughter becomes someone else when she returns to these objects with a creative agenda.

Then the artist establishes a contract. She reproduces favorite photos, selects fragments of them and reproduces them as ghostly images. Placed in the location where they lived on the shelves in the family room, the images appear even further away in time. More so than the photos themselves. She takes old plans of the family house and converts them into large inflatable objects. They are no longer the dream of a future space for all, but have been converted into split skins of objects that the daughter knows were precious to her mother. Like an archeologist in her childhood home, she rescues precise shadows, but not just any shadows, precisely those that were reflected in the blinds of her mother’s bedroom.

The central piece on display is the table where the family gathered. Over it, dangle images of the mother’s old cookbooks, of the dishes she prepared and the edible gifts she was lovingly offered at the end. The artist interposes metallic thread and beads among the images. She imagines herself treasuring these memories when she captures the reflected light, when she passes time with what are now objects, but once were a promise of life, of reciprocity. This cycle is affirmed by the oval shape of the table. With the help of these objects and actions, it is impossible not to return to the flow of giving that simultaneously nurtures, seals affections and creates daily memory. To furnish and inhabit the circle of gifts in order to keep it alive and not forget.

Finally, contradictorily, these gestures do not create meaning in themselves. It is impossible to separate them from the mother’s presence, because she was the first choreographer of what are now leftover scraps. It is the right and privilege of the daughter in mourning to decide what will last in memory, her memory. She can rescue, choose, pay attention, invest time in a legacy and thus re-acquaint herself with it. But it is the absence of the mother through “that tenuous fluid that must be protected forever,”* that not only initiates the creation, but makes it into an offering.

(*Henri Michaux, “We two, still.”)