Inside Out

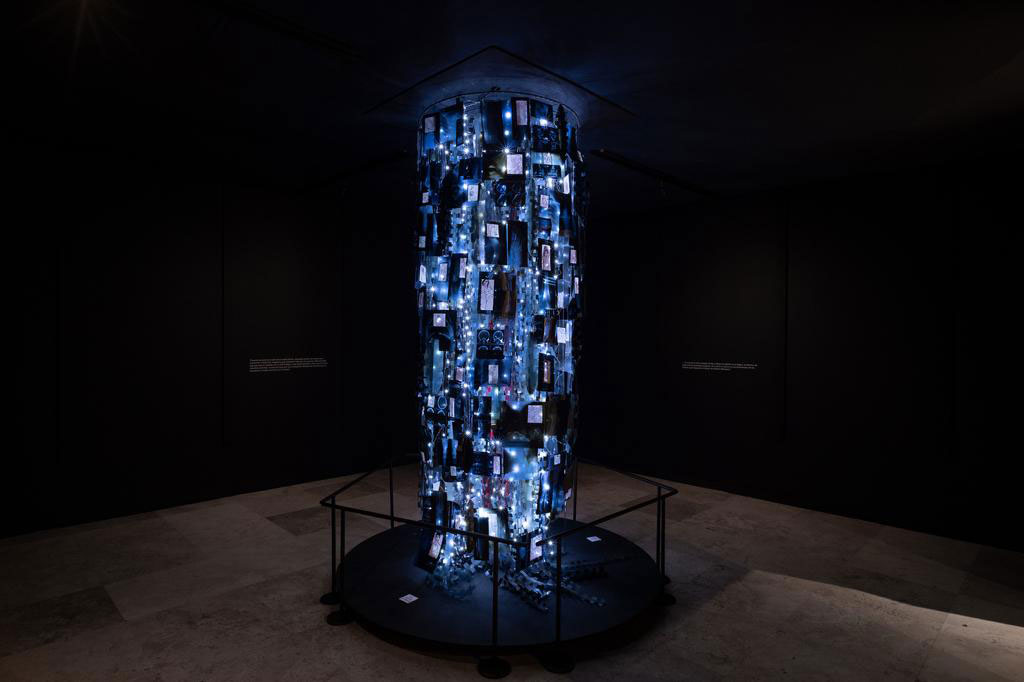

X-Rays, and textile

length: 3.mts

diameter: 1mt

It is astounding the way in which the past and its objects inform us about the present. By placing a work of contemporary art in a history museum, it is immediately recontextualized and strengthened because the spaces of history offer us the possibility to approach the aesthetics of those who preceded us and who never became extinct at all, but were transformed generation after generation.

Although it could be said that a work of art always dialogues with the past, we do not have the opportunity to approach the conversation that is generated between a permanent collection and a contemporary artistic piece every day. This experience, enriched both by the collection and by the work, is why visitors are invited to exercise this reading from their own perspective and recognize more connections than the ones I will list below.

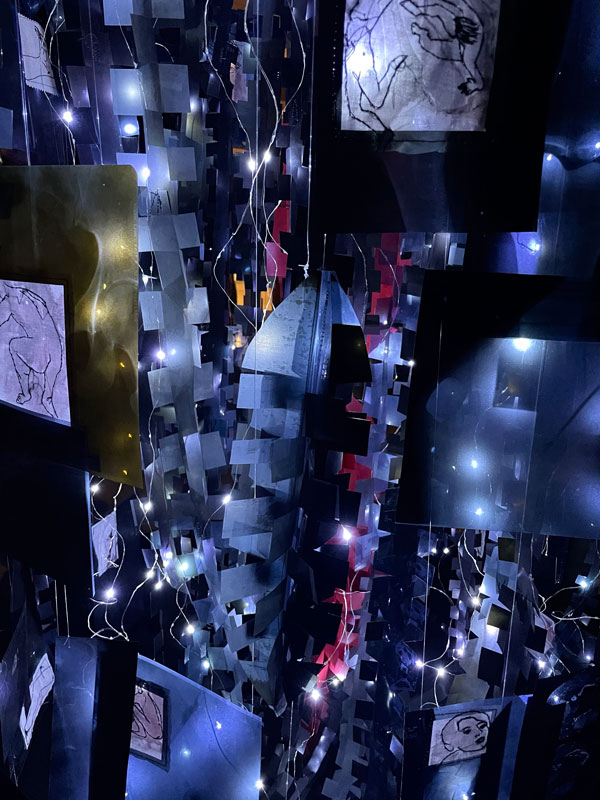

The multimedia sculpture Inside Out by the textile artist Miriam Medrez (Mexico City, 1958) shows a continuous research for how a body can unfold. Miriam Medrez shows us ways we can reconfigure the limits of our identity. The artist works from one to multiple, from the body to the community. But the most interesting thing about her practice on the body is how she creates a new system of signs, a visual language that appears as a writing system. I dare to say that the encounter between matter, form and drawing is similar in its logic to the sign system of ancient writings, as we see it in the facsimiles of the codices of the Museum of Mexican History.

On the other hand, talking about the structure of the installation, we see how the verticality and the layered construction look like leaves that refer us to the shape of a tree. In a subtle way, it speaks to us of a certain collective genealogy (stories told by the medical records of the Xrays), at the same time that it echoes the symbology of the tree of Mesoamerican cultures, a sign that is maintained and reinterpreted throughout the colonial era as we can see in the miscegenation between the tree and the Christian cross.

Inside Out is a sculpture made up mainly of X-rays that, as the name suggests, is a transposition between the inside and the outside. In technical terms, an X-ray is a photographic negative. Using the negative to reveal another face of reality has been a recurring event in the history of aesthetics. In the museum, there is an example of this with the presence of a Tarascan tripod bowl, dated between the years 1300 and 1512 and painted in negative, that is, with designs made with liquid wax that when going through the firing process, they fall to reveal the pattern drawn below.

Going back to the sculpture, and as I already mentioned, the X-ray is the quintessential photographic negative, the eye that shows us the bone, but also the anomaly: the sick body. Being composed of negatives, this installation is nocturnal: it requires internal light to be seen. When the structure is illuminated from within, parts of bodies that make up the Inside Out appear; images that contain stories of unknown people who were dealing with the disease, and that now appear as an anonymous collective memory, which echoed me with the small collection of ex-votos found halfway through the museum.

Although the textile material is less present in this work by Miriam Medrez than in other pieces, it is the heart of her practice. The visitor has numerous opportunities to encounter the textile’s presence in the Museum of Mexican History, either from the technique and the artisan vestiges of Mesoamerica, and later from the manufacture of henequen and cotton, or from the dresses preserved from different periods. The textile is a second skin in our daily life, but the artist uses it to show us the naked body as a proposal, more than for the origin, for an archaism and common place of humanity in which we all belong and inhabit.

Miriam Medrez addresses questions that history also addresses in the construction of a collective memory: What is a body? Is there a collective body? Is it possible to open a body without touching it? This installation reveals an important problem: Is the interpretation a subjective element of the experience? Is science the counterpart of subjectivity? From a scientific reading, the luminous is the healthy, while, from a spiritual point of view, the dark is the necessary contour and the essential material finiteness to perceive the luminosity. From the perspective of our Mexican history, it has been necessary to search for the vestiges and find them in the darkness of the subsoil to shed light on our present and our heritage. Likewise, Miriam Medrez, by showing us the bones and organs of people, with their own history that we will never fully decipher, puts us before the questions that historians ask themselves when building stories from the narratives and objects of the past, and that make me wonder to what extent is truth a phenomenon of interpretation?