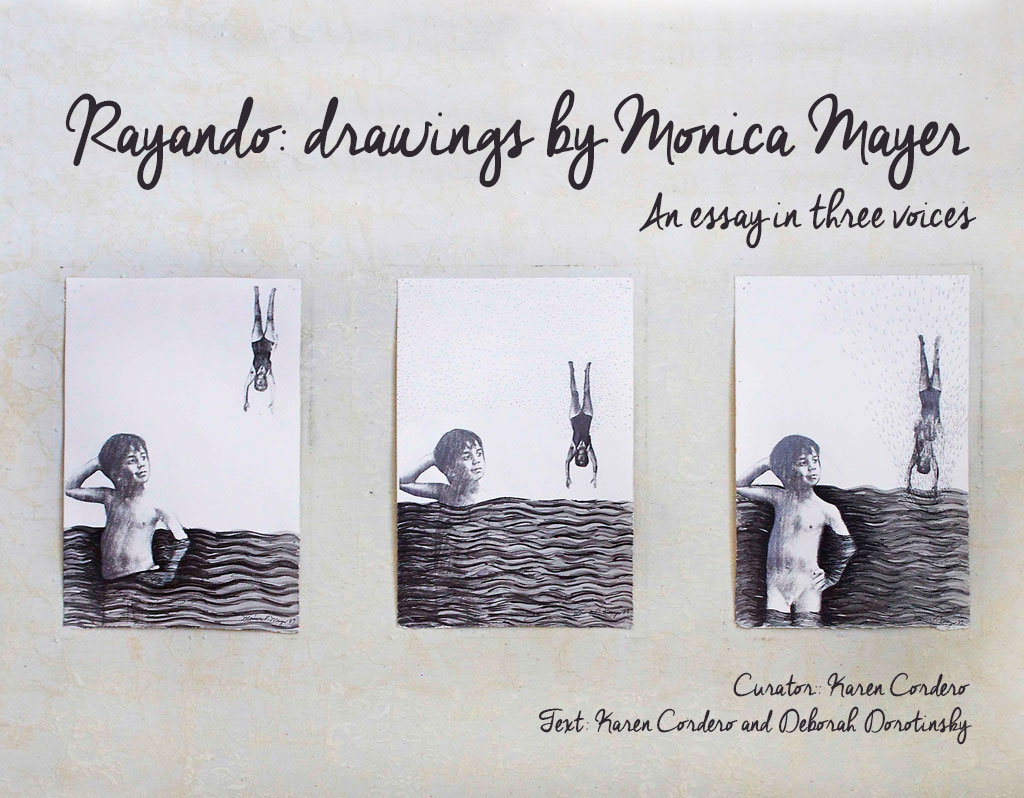

Rayando: drawings by Mónica Mayer. An essay in three voices.

Rayando: drawings by Mónica Mayer.

An essay in three voices.

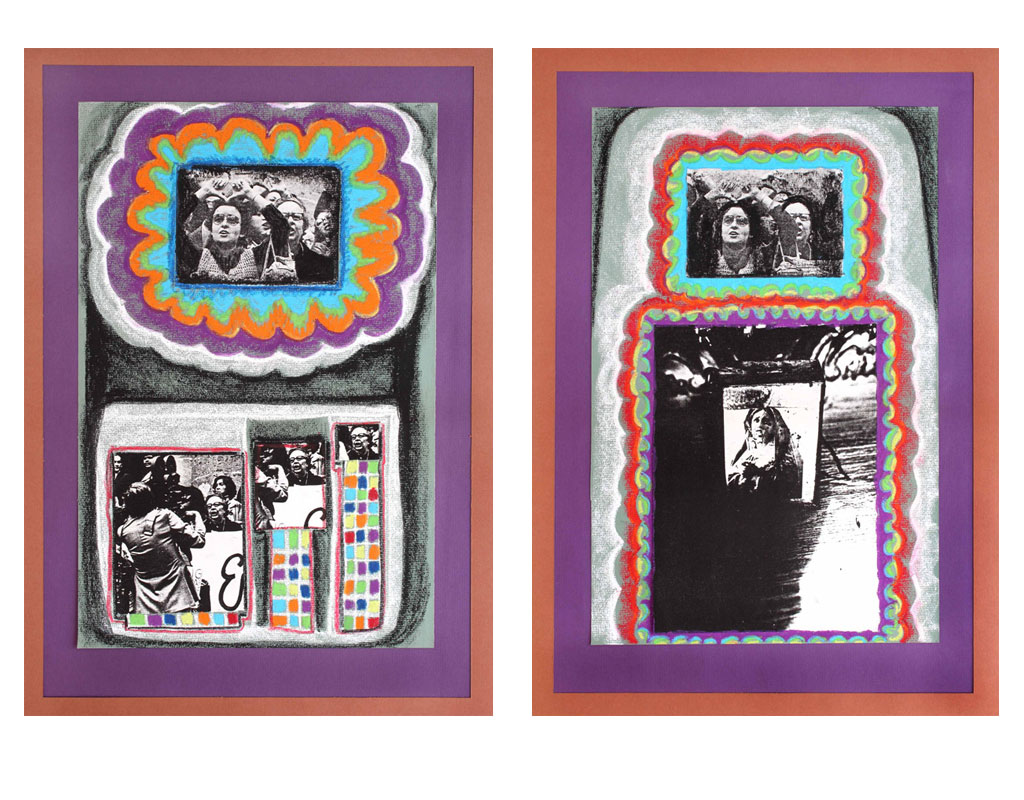

Monica Mayer is best known as an artist who focuses on feminist activism particularly through performance art and as one of the two members of the collective “Polvo de Gallina Negra” (Black Hen’s Dust) that she founded with Maris Bustamante and “Pinto mi Raya” the two-person group she formed with Victor Lerma. She also organizes feminist art workshops, works with archives, curates exhibitions and, throughout, has always been drawing. Her drawings—large, medium and small--almost literally paper the walls of her house. And since she works in series, they are many, many of them.

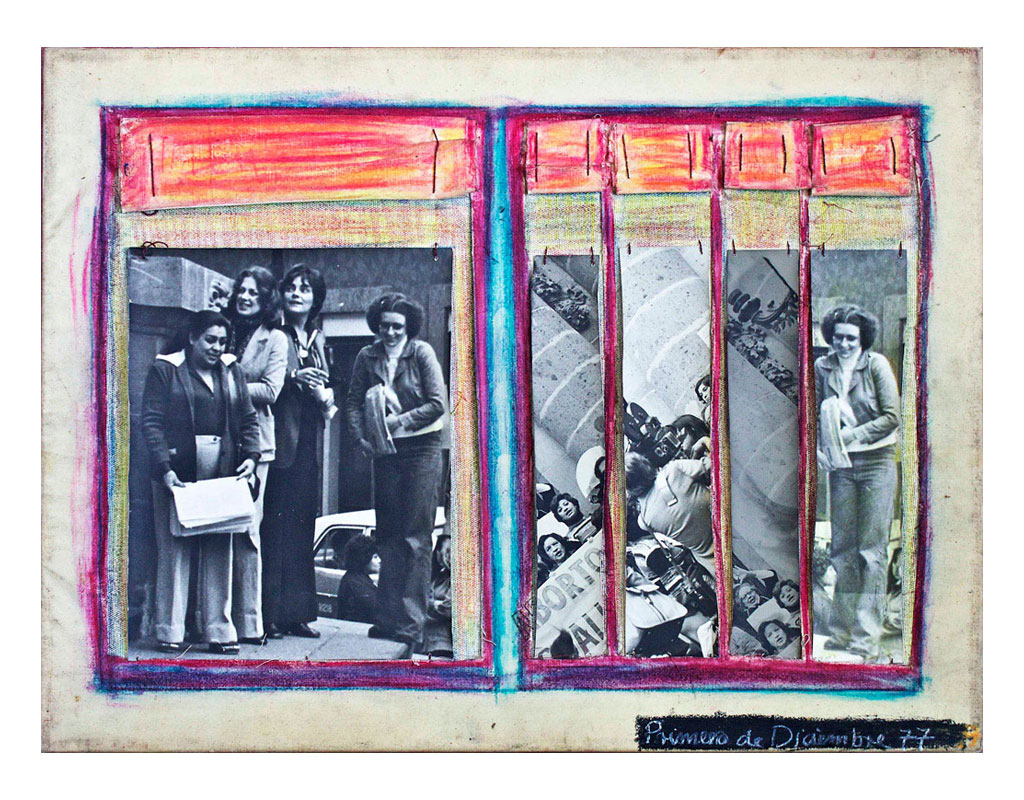

[Since the 1970s] Monica […] belongs to the group of intensely active feminist artists, as is evident both in her performances and her drawings. Between 1978 and 1980, she participated in the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, California, where she collaborated with “Ariadne: A Social Art Network”, the group formed by Susanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz, and with other collectives. In 1980 she obtained a master’s degree in Sociology of Art from Goddard College in the US with the thesis “Feminist Art: An Effective Political Tool”.

Deborah Dorotinsky

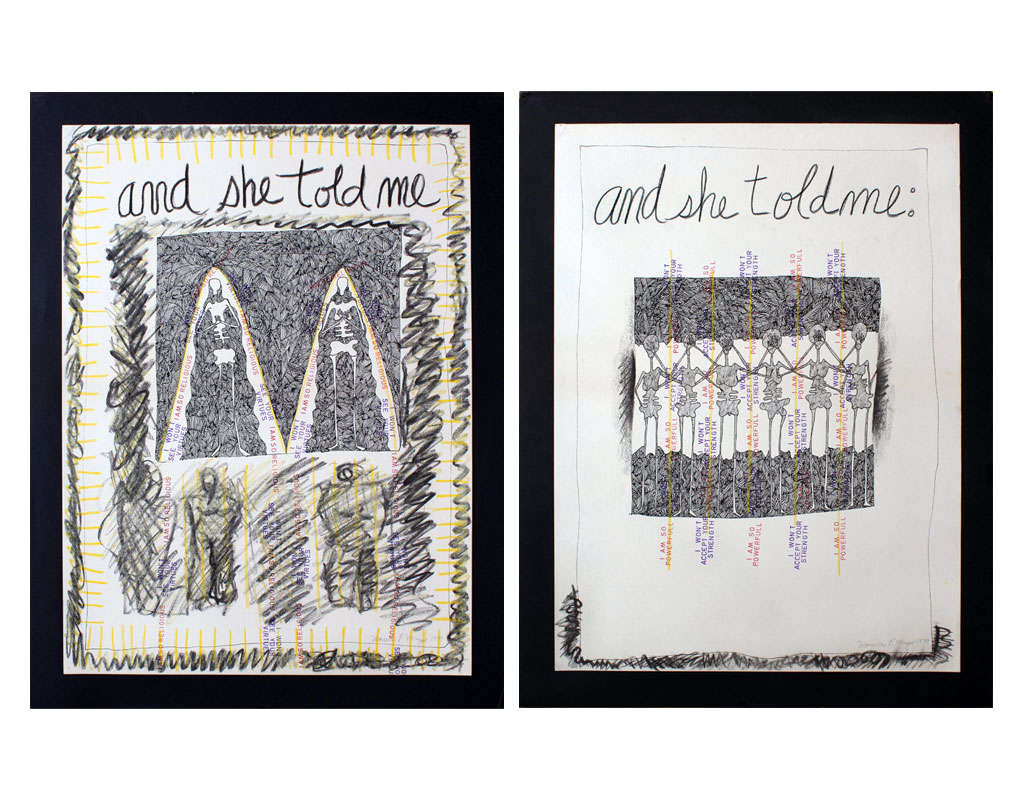

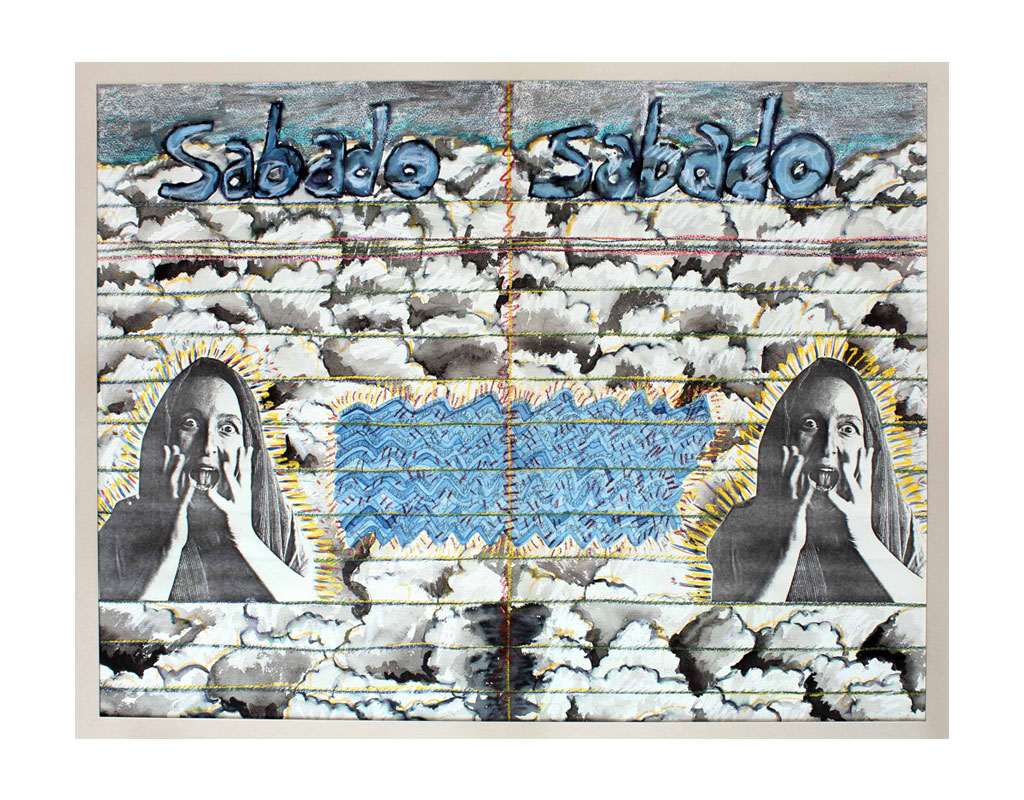

The often unwieldy dimensions of Mónica Mayer’s early drawings—that contrast with the intimacy often associated with that medium—together with her surprising productivity in those years, reveals a scenario of work that insists on giving voice and image to subjectivity and daily life, as a means of survival that speaks to us of the urgent need for “a room of one’s own” so eloquently characterized by Virginia Woolf.

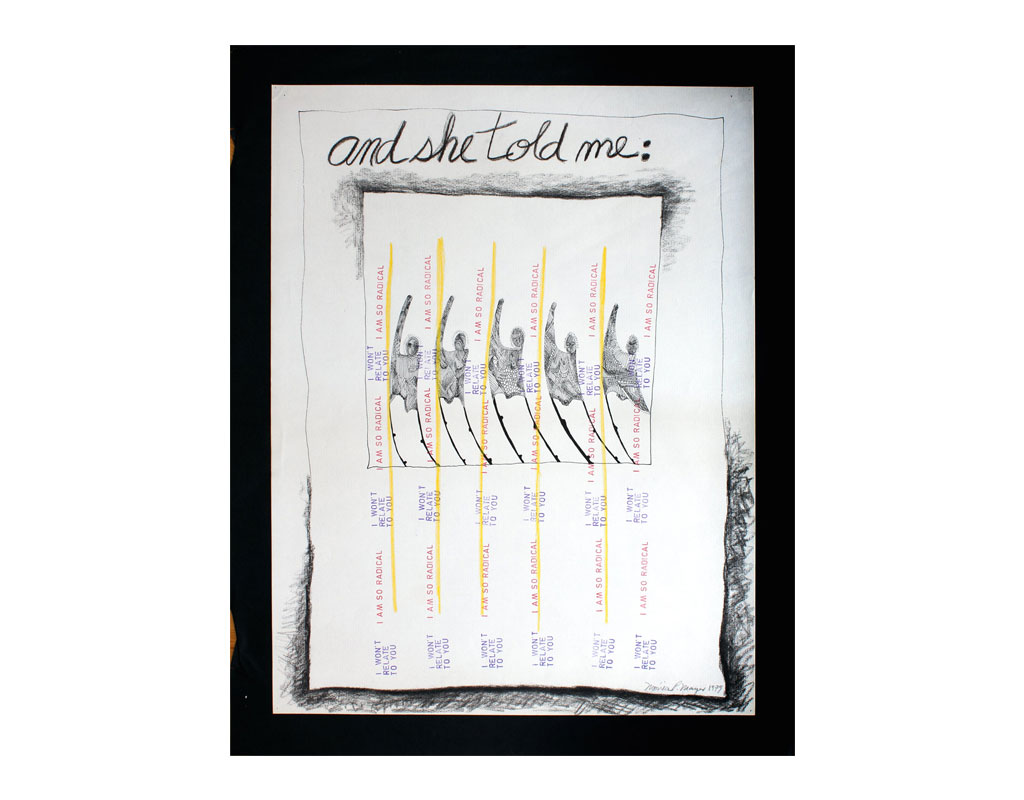

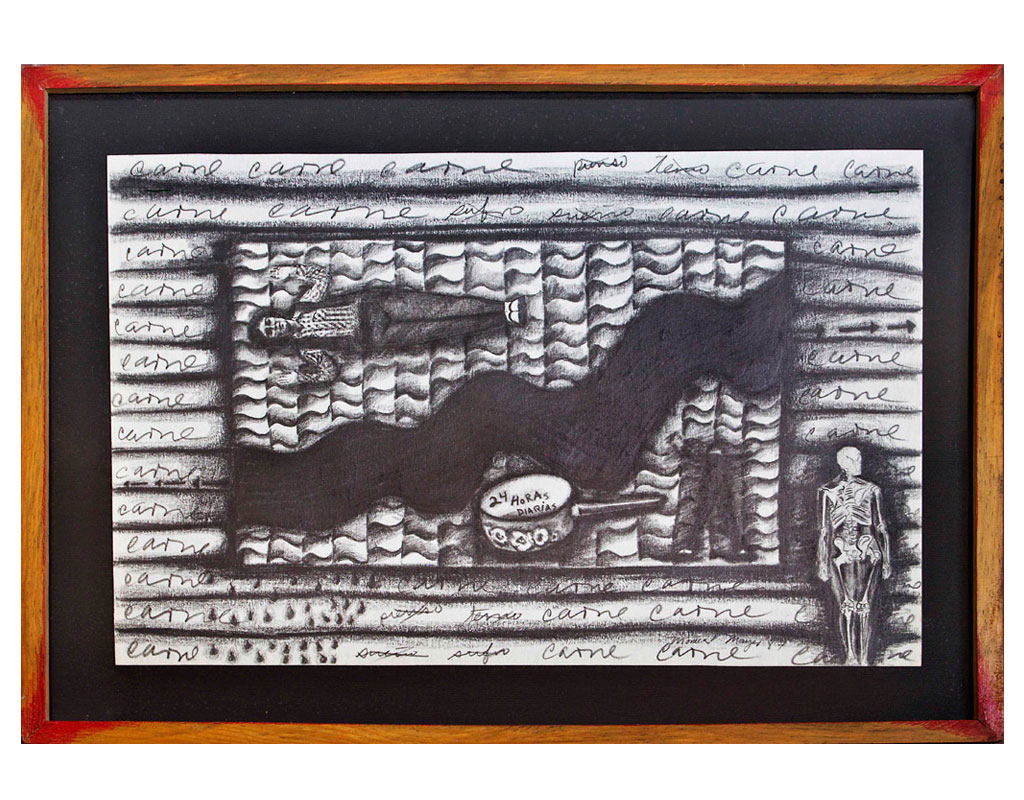

An insistence on words, echoing in ironic and subversive form the conventional primary school punishment in which the admonished student has to fill the blackboard with his or her reiterated declaration of conformity, emerges here in the repetition of the names of objects or the phantasms and stereotypes that compose the symbolic universe of Mónica Mayer.

Karen Cordero

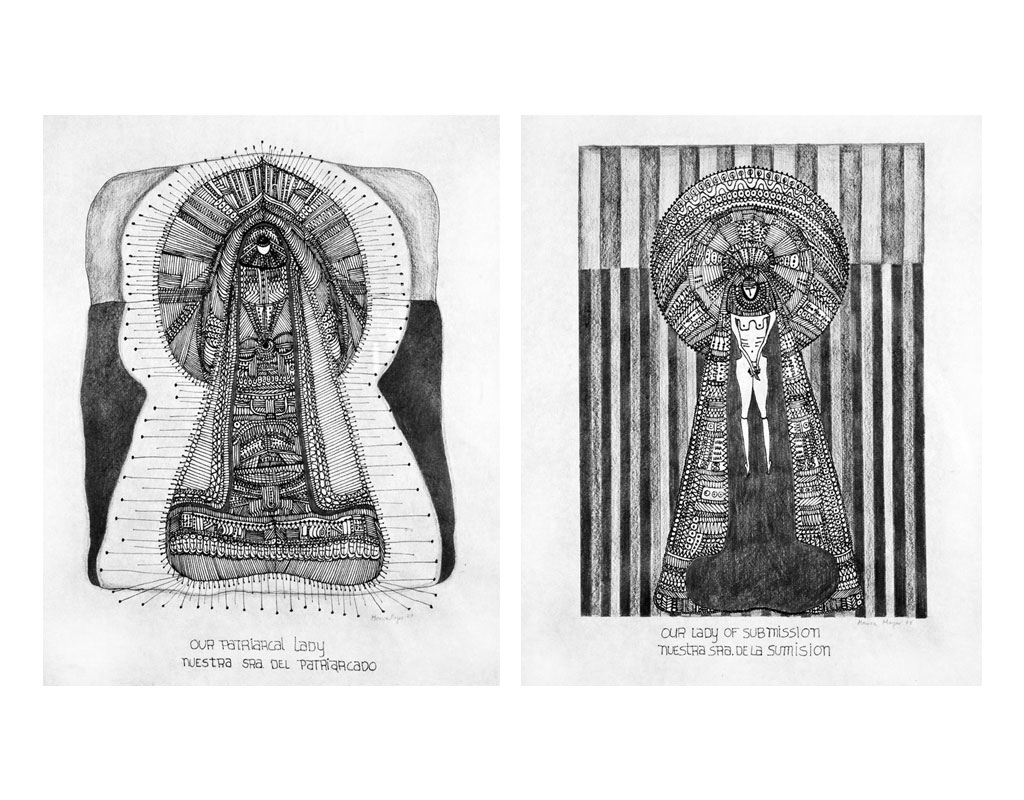

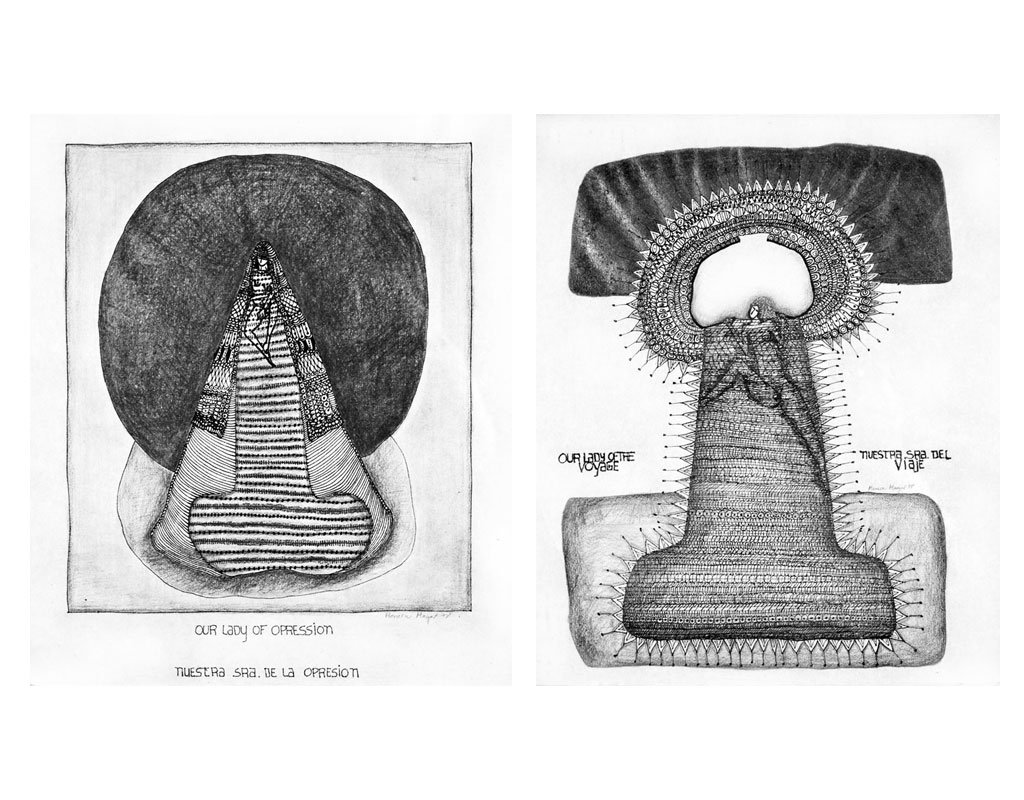

Monica has always drawn. It is curious that her performances are well known, yet her abundant production of drawings is not, though they

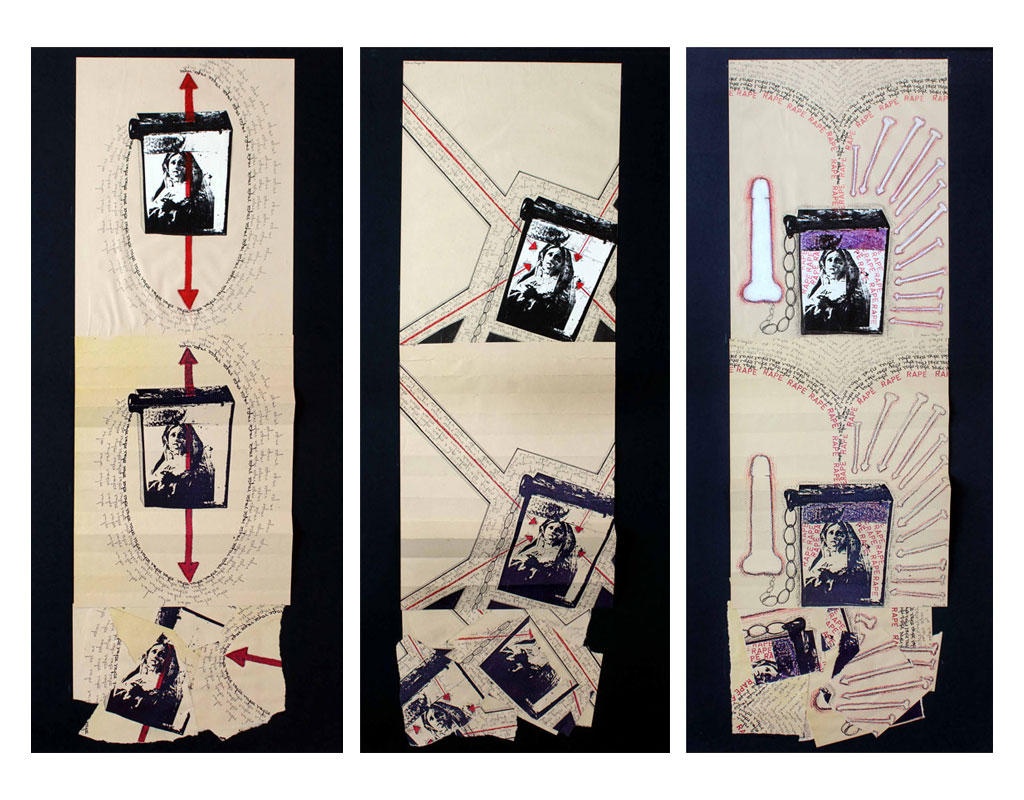

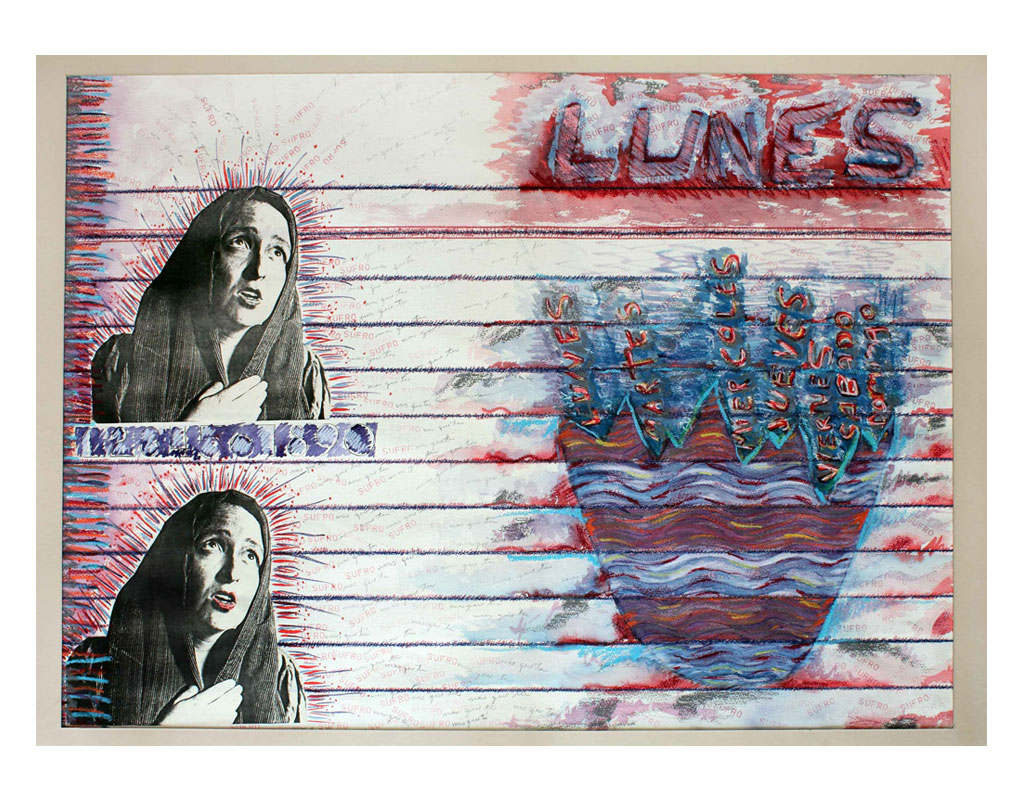

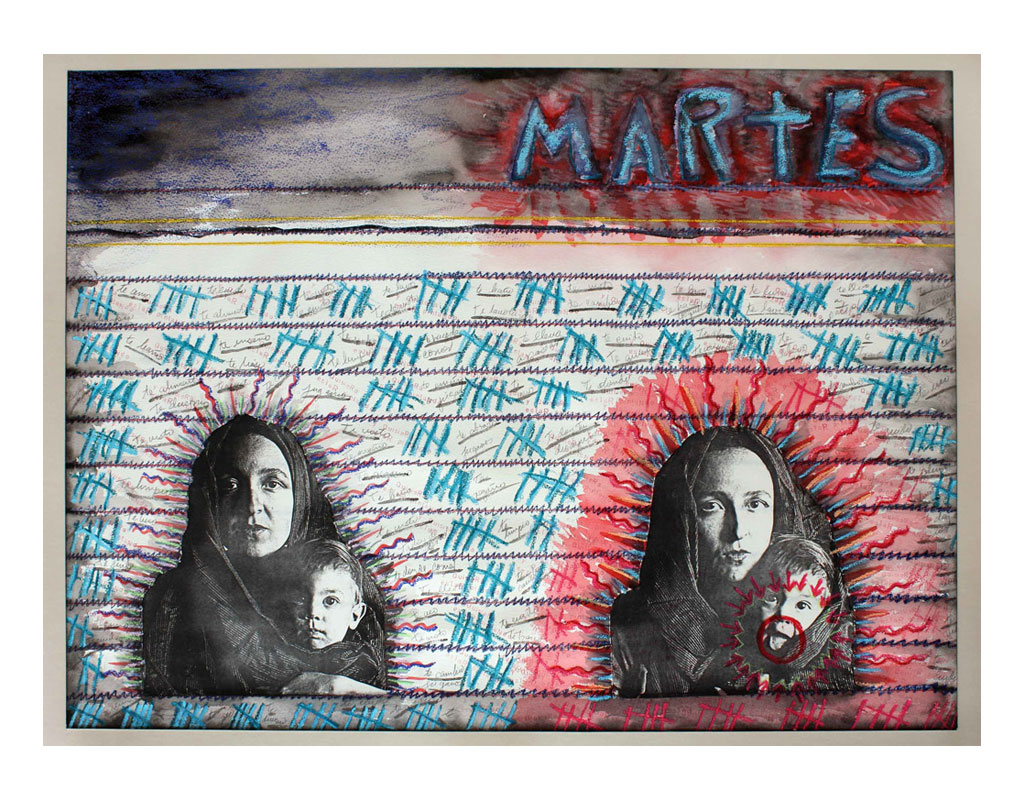

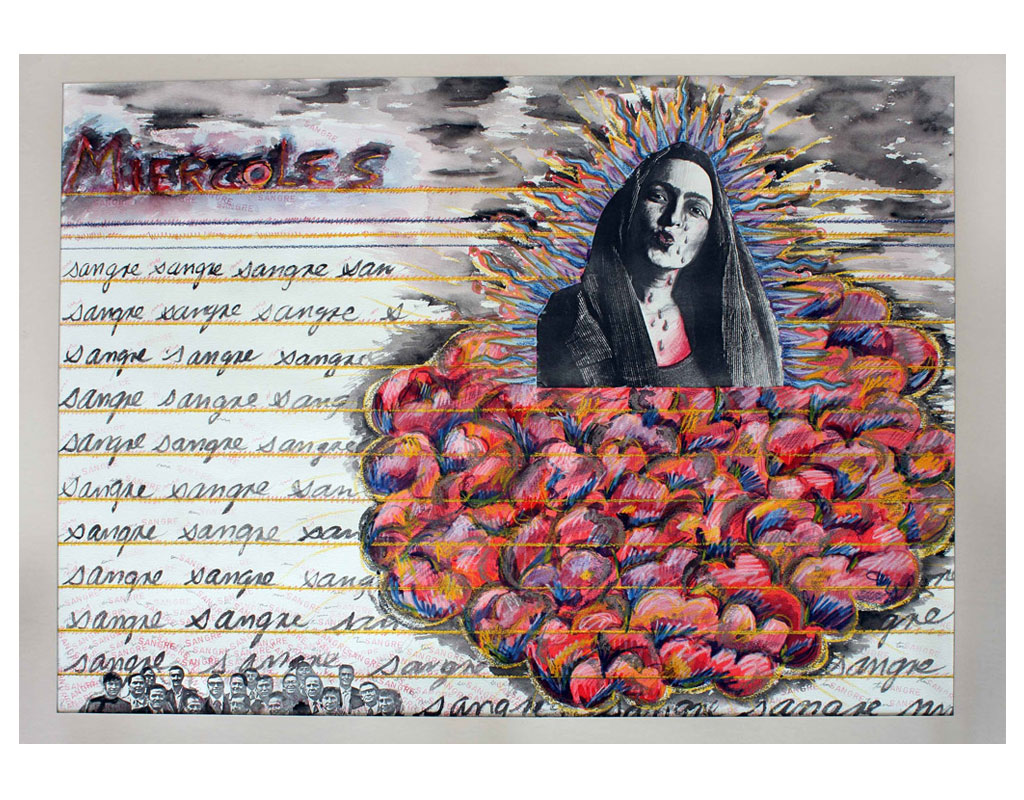

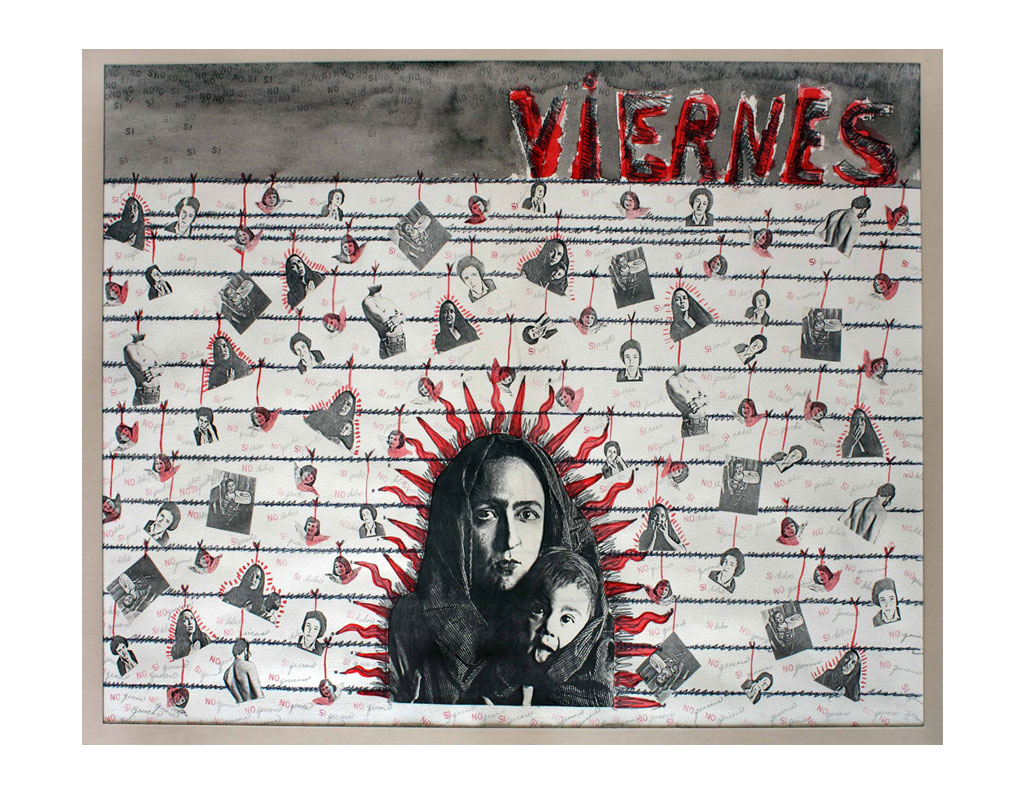

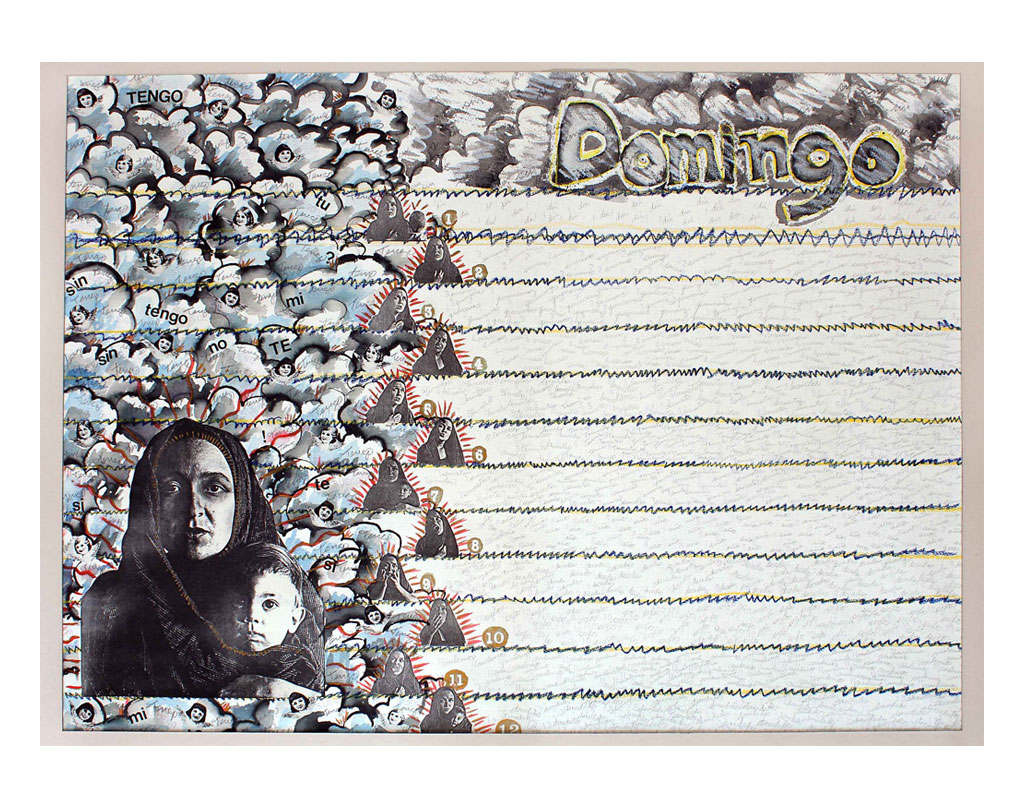

were frequently exhibited during the early years of her career. In 1980 […] Mayer presented a show entitled Silencios, vírgenes y otros temas feministas (Silences, virgins and other feminist issues) at the Anglo Mexican Cultural Institute. At that time, several of her pieces were censored by the organizers. In these mixed media works, Monica uses the icon of the Mater Dolorosa to question, from a feminist standpoint, the ideals of sacrifice, submission, abnegation and asexuality represented by the virgin’s image.

Perhaps tacitly, or perhaps not so tacitly, she also questions the income received by the Church through charity (and women’s sacrifice) since the image of the Virgin appears on a collection box which was photographed, then photocopied and then glued onto the paper on which she draws other icons that represent the oppression of women: the collection box chained to a phallus and framed by the word “rape” repeated many times in the shape of a heart; the same box floating on clouds, as if to indicate an unreachable goal; or with a cross superimposed on the box and the word “rape” inscribed several times on the paper..

Deborah Dorotinsky

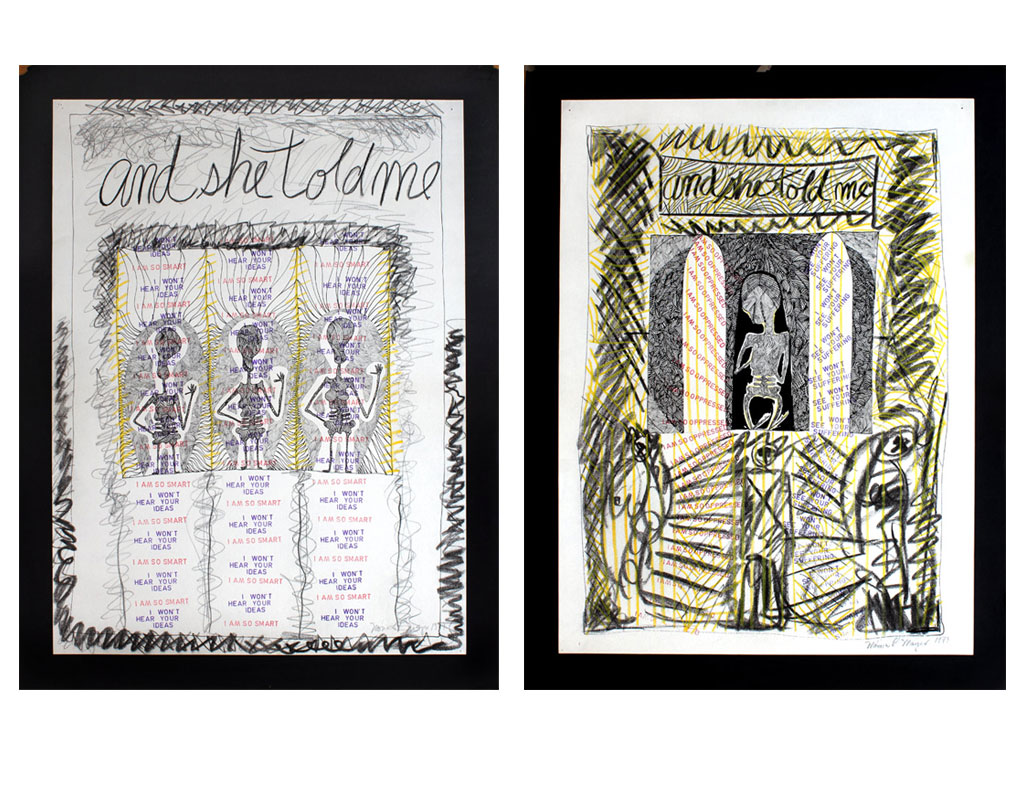

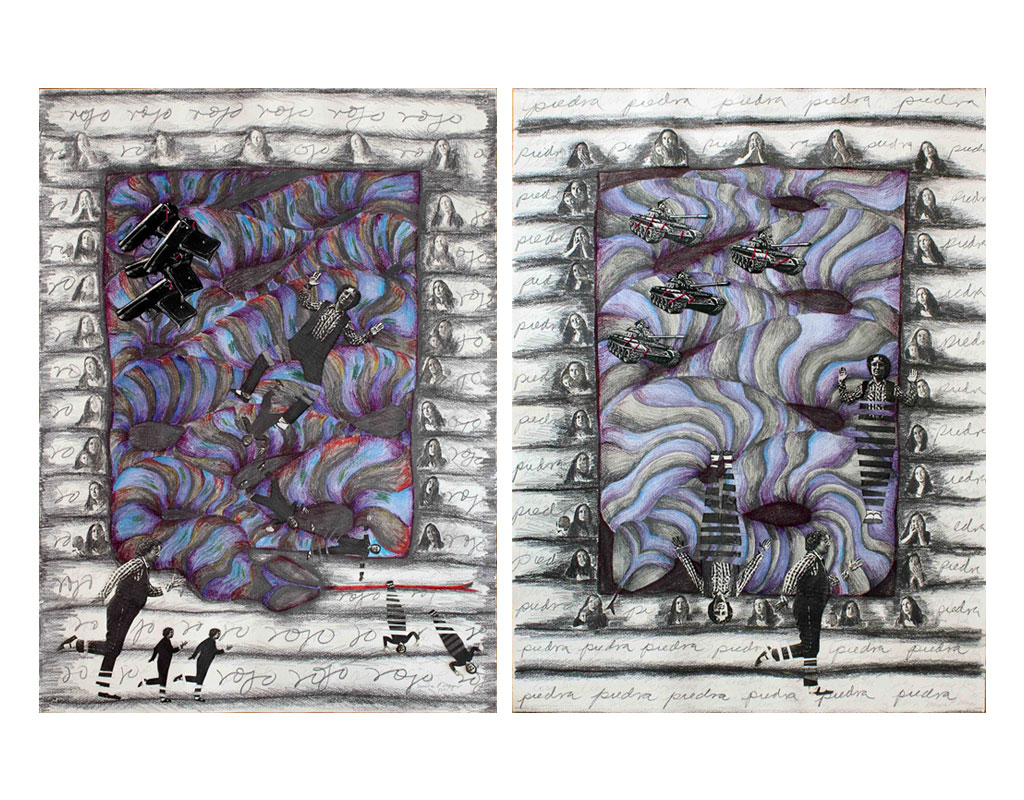

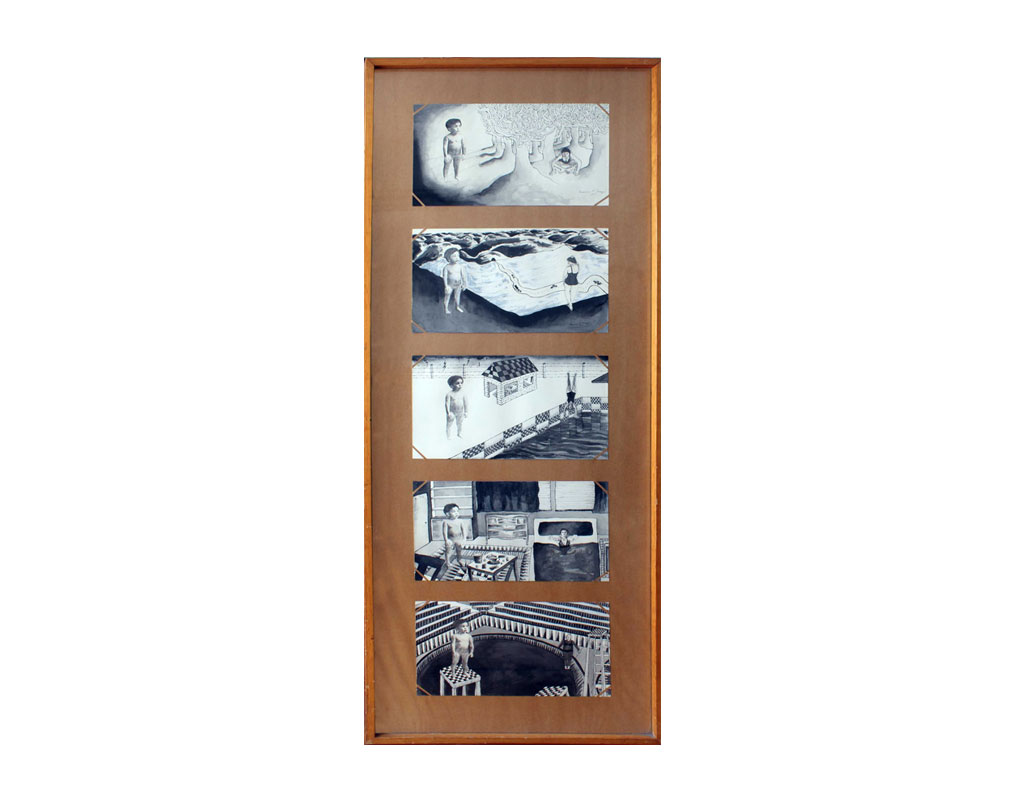

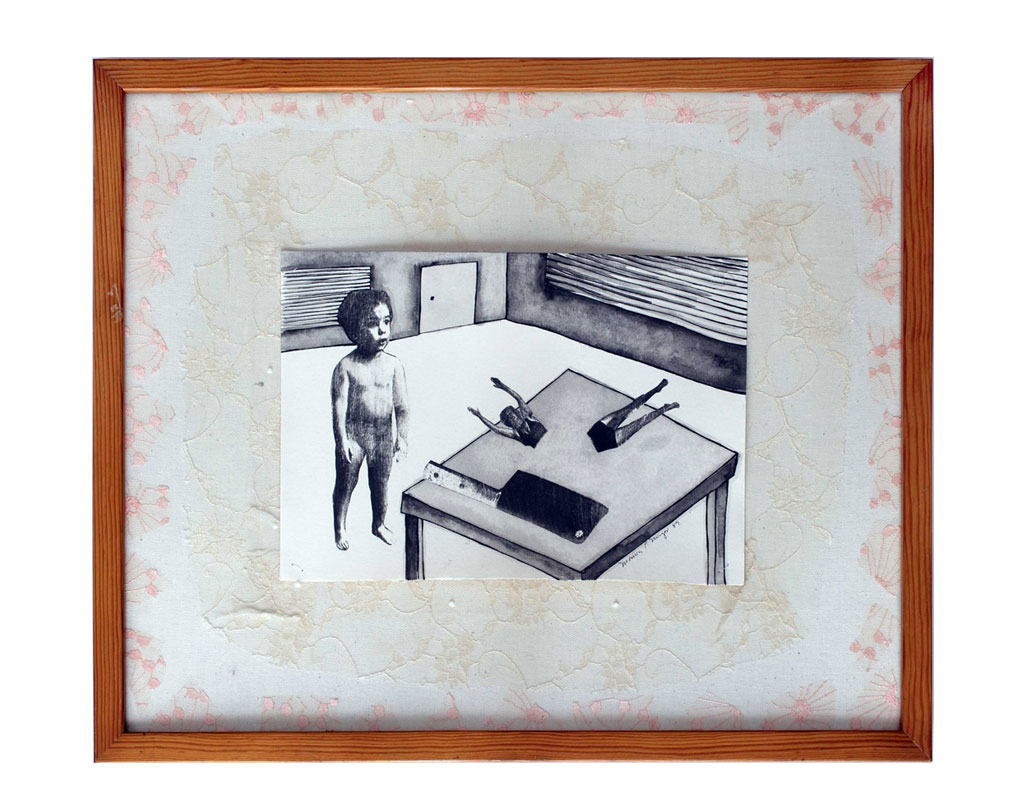

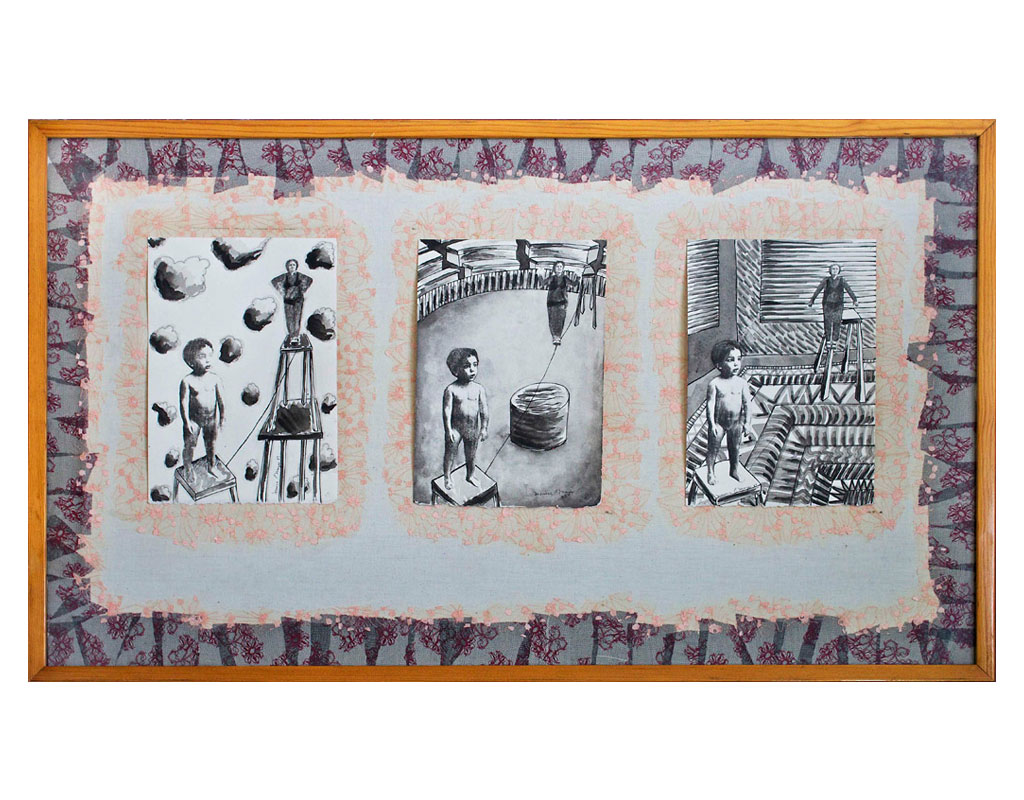

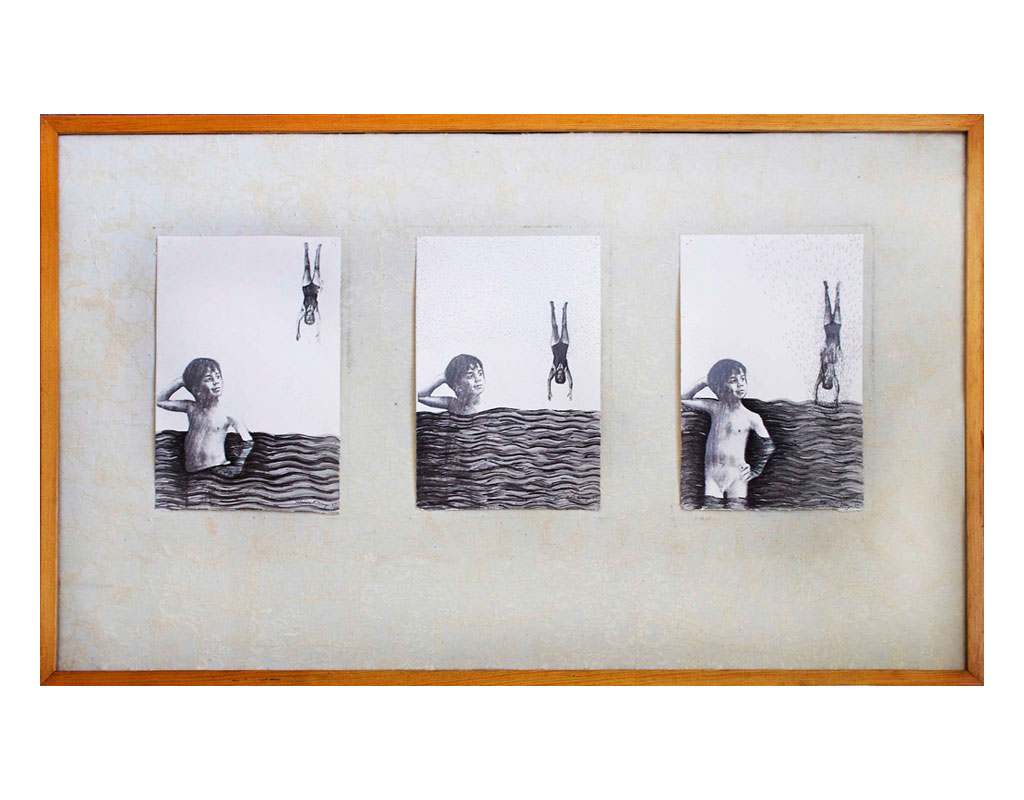

The artist reflects visually on her subjective experiences as a woman-- motherhood, work, exercise, the body, sexuality-- as well as on the collective domestic experience of many other women by using icons such as the chair, the house, children, the iron or the telephone. Monica uses herself as her model, photographing herself in a bathing suit or wearing overalls and a shirt, and wearing low-heeled black shoes, those very thin Chinese ones that look like black slippers. In her works from the eighties she transferred photocopies onto paper using acetone and then drew again and again over the ghostly

scratches left by the transfer, creating patterns and enhancing with graphite the surface of the spongy, rough looking papers she used. The figures do

not seek a horizon on which to stand; they appear in scenarios in which they seem to be floating, creating stories that in turn become series, comprising a cumulative visual narrative, page after page, that is both incisive and carefully detailed in its realization.

Deborah Dorotinsky

The written word—in cursive script, at once controlled and free—also obsessively invades the space of these drawings, acquiring an enigmatic poetic force as a result of its separation from a descriptive function. It interrelates the series of works, sometimes acquiring the role of a strange mantra that is repeated in an apparently infinite manner, sometimes alluding to activities that escape the control of calendaric time, and sometimes to memories.

The sense that assuming the role of a mother transforms everything—so powerfully evoked and analyzed in Adrienne Rich’s 1974 text Of Woman Born— is masterfully recreated in these large format works on paper, and the sense of fragmentation that they transmit in reinforced and reiterated in the treatment of materials and processes: collage, cutting and pasting, and sometimes sewing.

Karen Cordero

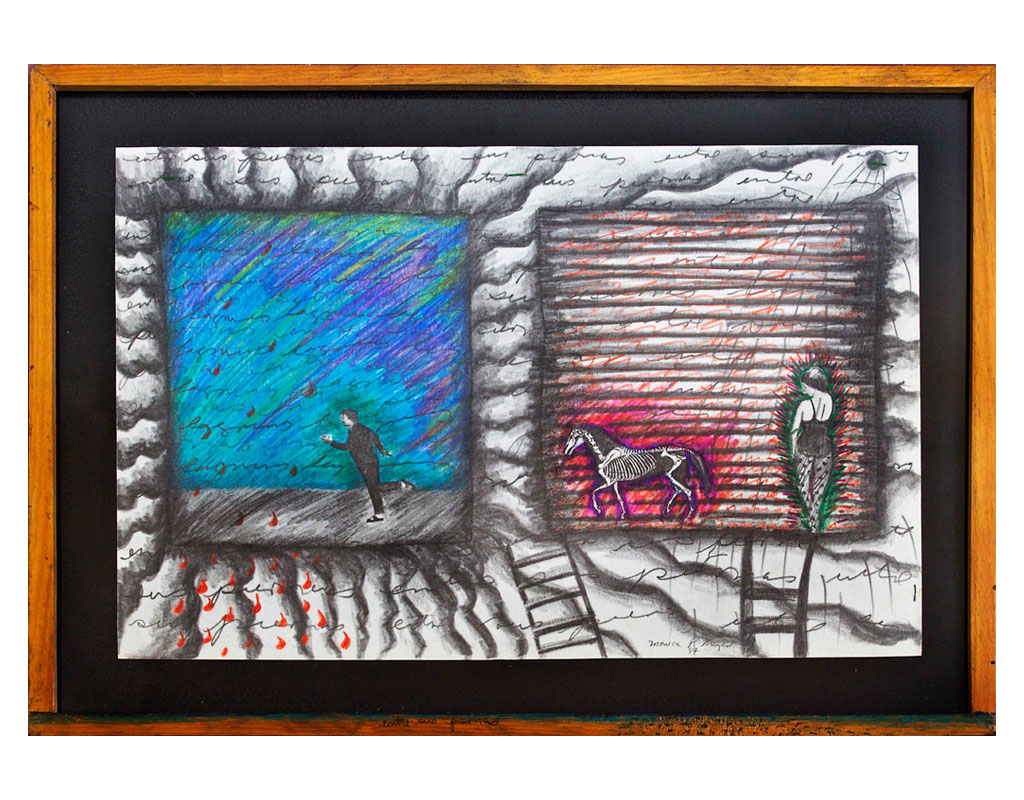

In 1987 Mayer exhibited “Novela rosa o me agarró el arquetipo” (Pink novel or the archetype overtook me) at the Carrillo Gil Museum. It

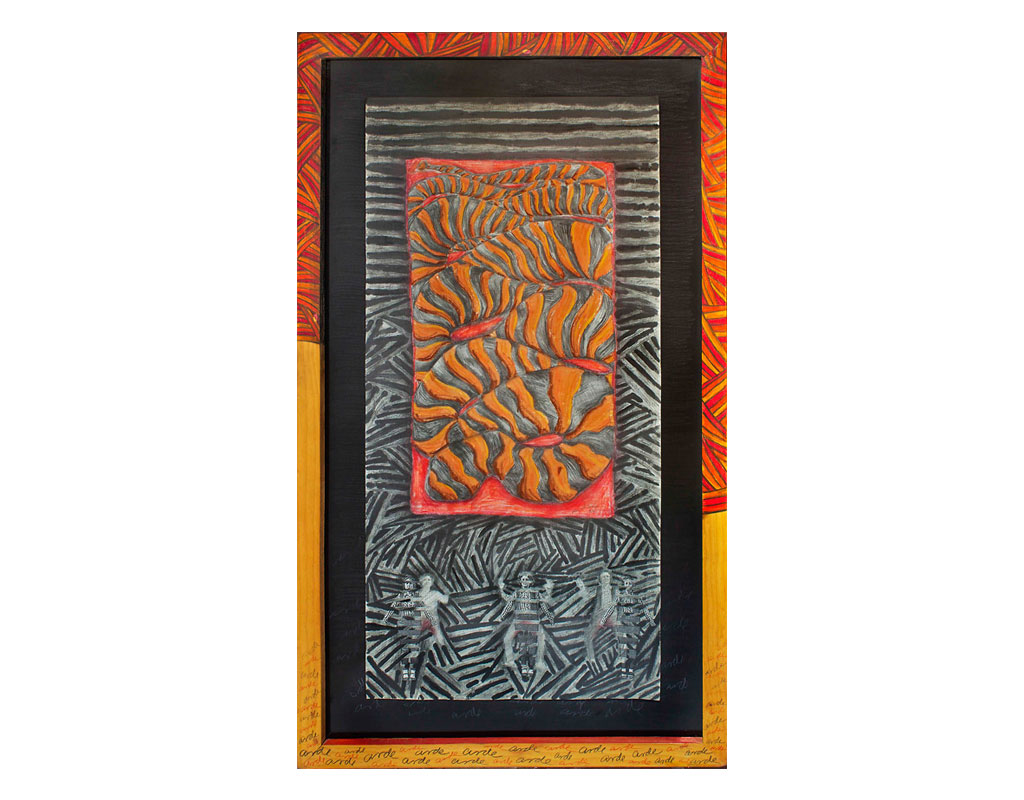

included 14 series or “chapters” that comprised this “pink” novel* which, in fact was more “dark” in the words of Magali Tercero in the prologue to the catalog. In these drawings Monica is the protagonist, and she is accompanied by snakes, houses, domestic appliances, tables and chairs, horses, skeletons, war tanks, guns, hatchets, virgins, her son, her father, her grandfather. (…) They are very powerful drawings in which she uses the same photocopy transfer technique we saw earlier, introducing colors and patterns that overflow on to the mats and even onto the frames.

Deborah Dorotinsky

*A pink novel in Spanish is a “chick” or “girlie” novel.

The reiterated presence of a striped serpent coiling back on itself, together with the black graphite and the incendiary tones of yellow,

orange and red, clearly suggests a disquieting and imposing erotic component in the symbolic equation of this works, even though their appearance is very different from the stereotypes of erotic art presented by the patriarchal canon.

Karen Cordero

These works dislocate our compositional expectations. A corporeal sensation of instability emerges in them with an undeniable, overwhelming force.

They are works full of things, lines, textures, objects and images, and nonetheless they remit us inexorably to a sense of emptiness, and of desire.

Karen Cordero

The little attention Monica’s drawings have received can be explained in part by the effectiveness of her work in the eighties with the Polvo de Gallina Negra and Tlacuilas y Retrateras collectives, in disciplines such as action art, conceptual art and feminist performance art, which served as a way of bringing together artistic production and women’s conditions. Undoubtedly, part of their fascination is the catharsis that these drawings generate in me, as they connect my experience as a woman and that of the artist through this voyeuristic visit to Monica’s personal imaginaries, and to the fact that much of what her work deals with in terms of domesticity, motherhood and even work is still so true. Thirty years after they were created, their relevance is disquieting.

Deborah Dorotinsky

The texts by Deborah Dorotinsky are from the essay “Mónica Mayer, dibujos”, which will be published shortly in Revista O.

Photography: Jorge Alberto Arreola Barraza

Acknowledgements:

Nosotrxs: lxs otrxs collective--Liliana Marín, Azucena Blanco, Josué Lara, Gerardo Pineda, León Bernal

Víctor Lerma

Yuruen Lerma

![]()

This project was supported by the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes through the Programa del Sistema Nacional de Creadores, 2014.