A Room of One's Own

|

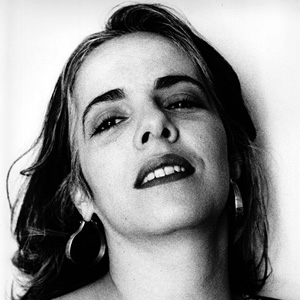

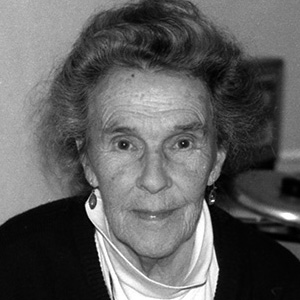

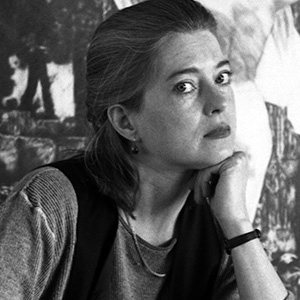

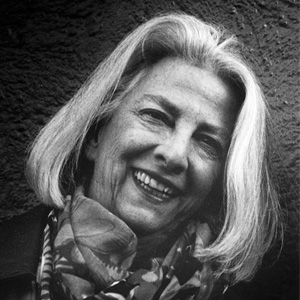

Marta Lamas Anthropologist |

Aline Davidoff Writer |

Luna Maran Filmmaker |

|

Magali Lara Painter |

Nadja Massum Photographer |

Pilar Medina Choreographer |

|

Maya Goded Photographer |

Annette Fradera Musical Producer |

Ethel Krauze Writer |

|

Elena Garro Writer |

Elena Paz Writer |

Toni Morrison Writer |

|

Carmen Boullosa Writer |

Leonora Carrington Painter |

Diamela Eltit Writer |

|

Jesusa Rodríguez Actress & Theater Director |

Liliana Felipe Singer & Composer |

Gabriela Malvido Ecologist |

|

Laura Esquivel | Betsi Pecanins Writer | Singer |

Elena Poniatovska Journalist& Writer |

Cristina Pacheco Journalist |

|

Diana Bracho Actress |

Tania Álvarez Choreographer |

Angélica Aragón Actress |

|

Sarah Minter Filmmaker |

Carla Rippey Painter |

Eli Bartra Philosopher |

|

Mariana Yampolsky Photographer |

Graciela Iturbide Photographer |

Tedi López Mills Writer |

|

Lucia Melgar Literary Criticism |

Lila Downs Singer & Composer |

Sara Sefchovich Writer |

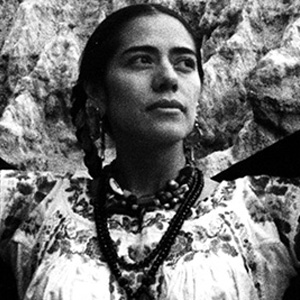

Lucero González, la fuerza del retrato

by Eli Bartra

One of Lucero’s specialties is portraits. She began exploring this genre in the late 1980s through her work in photojournalism.

I believe her affinity for portraying women is linked to her feminism: she wants to show the faces and names of women who have had an impact on the country’s culture. Thus she creates a record of their daily work, for today and perhaps even for the future, so that when only their creations remains, their faces are preserved forever by Lucero’s lens.

Her portraits are not formally posed, although some appear to be. People do not usually pose for her, they are simply there, and she takes their picture. Some may be aware of the presence of her camera, but if she can use the element of surprise she does. Surprise is important to her. In fact, she takes two different types of portraits: those she takes with an element of surprise and even though her subjects know she is going to take a photo, they do not pose, she catches them when they are absorbed in an activity. In others, she asks the subject to move or pick up an object. In this vein, for example, is the portrait she took of Graciela Iturbide which is very well thought out, constructed and extremely sophisticated. She portrayed her as a soul in purgatory: her eyes are closed and there is a box painted with flames on her chest in the foreground. Lucero even included some tiny porcelain hands from Graciela’s collection.

Perhaps the fact that Graciela Iturbide is also a photographer forced Lucero to produce a carefully crafted photograph rather than leaving it to change. I imagine photographing an accomplished photographer must have posed quite a challenge. Perhaps it is easier for Lucero to photograph women because she establishes a more direct relationship with them. She feels comfortable because there is more permissiveness; she seems not to censor herself with women. When she asks them to pose, she may request a lowered shoulder, or a certain stance. Portraits are a way of getting to know people she admires, and through them, she also reveals herself.

In the portrait of British-Mexican painter Leonora Carrington, the subject’s rather feline energy is accentuated by the inclusion of a cat in the image, staring defiantly at the camera. They are soul mates closely bound into a single unit by the action of Lucero’s lens. This photograph could well be called Leonora-cat.

The artist has said that although she “specializes” in shooting female artists, taking photographs of unknown women is just as important to her as portraying someone renowned or even famous. In her quest to learn about a person through photography, she uses the same method. She tries to perceive, feel and intuit who the person in front of her is, be it the writer Elena Poniatowska, or Layla López Musalem, a friend from Juchitán. She has also explored a different way of representing her subjects, with what she calls, “constructed portraits”. For example, she has a series on the goddess Xochiquetzal (plumed flower), whom she sees as a Venus figure, the goddess of love and sensuality, hence the nude photographs. And here is it essential to consider the background of the image. She also constructs the context, through the walls of the ruins of Xochicalco and the mountains of Tepoztlán.

Lucero uses a manual Nikon FM camera and three different lenses: wide angle, normal and telephoto. She never uses flash. She forces the film if necessary, which is why some of the images look grainy. When there is very little light, she prefers to use ISO level 400. In other words, she uses technique, but with as little artifice as possible. She does not take studio portraits and instead uses natural light, and occasionally, a light source. Because of this her images usually have a high contrast. Lucero likes to control her camera. She tends to take central plane portraits of just the face, which may be why Lucero’s photographs are usually so powerful. Power, in fact, is her main feature. Lucero González has “tamed” the lens to suit her wishes. You could say she wants, and I think she has managed, to empower and dignify women.

Perhaps the fact that Graciela Iturbide is also a photographer forced Lucero to produce a carefully crafted photograph rather than leaving it to change. I imagine photographing an accomplished photographer must have posed quite a challenge. Perhaps it is easier for Lucero to photograph women because she establishes a more direct relationship with them. She feels comfortable because there is more permissiveness; she seems not to censor herself with women. When she asks them to pose, she may request a lowered shoulder, or a certain stance. Portraits are a way of getting to know people she admires, and through them, she also reveals herself.

In the portrait of British-Mexican painter Leonora Carrington, the subject’s rather feline energy is accentuated by the inclusion of a cat in the image, staring defiantly at the camera. They are soul mates closely bound into a single unit by the action of Lucero’s lens. This photograph could well be called Leonora-cat.

The artist has said that although she “specializes” in shooting female artists, taking photographs of unknown women is just as important to her as portraying someone renowned or even famous. In her quest to learn about a person through photography, she uses the same method. She tries to perceive, feel and intuit who the person in front of her is, be it the writer Elena Poniatowska, or Layla López Musalem, a friend from Juchitán. She has also explored a different way of representing her subjects, with what she calls, “constructed portraits”. For example, she has a series on the goddess Xochiquetzal (plumed flower), whom she sees as a Venus figure, the goddess of love and sensuality, hence the nude photographs. And here is it essential to consider the background of the image. She also constructs the context, through the walls of the ruins of Xochicalco and the mountains of Tepoztlán.

Lucero uses a manual Nikon FM camera and three different lenses: wide angle, normal and telephoto. She never uses flash. She forces the film if necessary, which is why some of the images look grainy. When there is very little light, she prefers to use ISO level 400. In other words, she uses technique, but with as little artifice as possible. She does not take studio portraits and instead uses natural light, and occasionally, a light source. Because of this her images usually have a high contrast. Lucero likes to control her camera. She tends to take central plane portraits of just the face, which may be why Lucero’s photographs are usually so powerful. Power, in fact, is her main feature. Lucero González has “tamed” the lens to suit her wishes. You could say she wants, and I think she has managed, to empower and dignify women.