Leonora Carrington: Women Awareness

- Karla Segura Pantoja

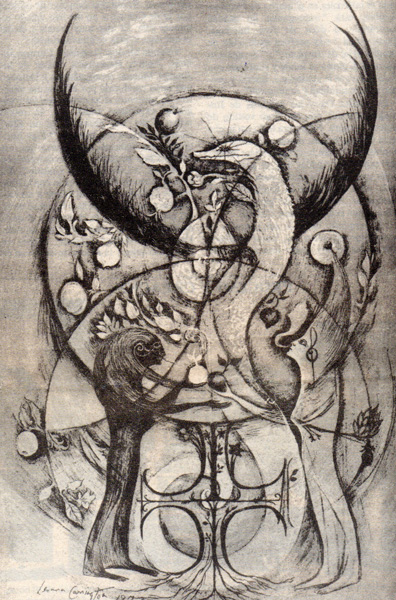

© Estate.Mujer Conciencia, 1972

In 1972 Leonora Carrington painted Mujeres conciencia.1 Two female characters, black and white, facing each other star the picture. They seem to be exchanging two opposite-coloured fruit, possibly apples. At the centre of the image there is an erected snake, coming from the core of a symmetrical cross whose stake contains a vegetal structure’s roots connected to the encircling line covering the three characters’ heads. The symbols in this painting are closely linked to those of the biblical myth of the expulsion from paradise. However, there is no Adam in this picture, only two women sharing the fruit of the tree of wisdom: conscious women.

In several interviews and testimonies, Leonora Carrington declares being conscious of the obstacles and difficulties related to the female artist’s condition. The sharp consciousness of the differences is the background of her biography and artwork. Even if Leonora Carrington did not affiliate definitively to any feminist movement, as a woman, she never stopped questioning ‘why we were considered as inferior beings?’2

Leonora Carrington’s feminist consciousness was born early on, considering the difference between her brothers’ education and her own, the only daughter of four kids. The early awareness of the iniquity between men and women fed her uncompromising rebellion and nonconformism. Her brothers had the right to play certain games that she could not play. Indeed, the abyss between men’s and women’s condition in British high society of the early 20th century could be hardly trespassed.

Leonora had to be educated in order to be a ‘lady’ and to be introduced to the court. While women’s education consisted of learning to read and write, learning French and basic mathematics skills, the access to art and science was strictly limited to men.

A natural since her childhood, Leonora Carrington had the attributes of superior intelligence: she drew, created stories, was ambidextrous and she wrote backwards, as Leonardo da Vinci did, so that her writing could be read in a mirror. Her mind went beyond the etiquettes she had to learn in the religious schools she attended, beyond good manners and high society’s conventions. A great mind, ill-adjusted to the rules since her childhood, expelled from various Catholic institutions. Women’s education by women could also had formed her feminine consciousness: the Irish legends of Tuathá de Dana’s White Goddess that her mother and her nun used to tell her, along with her French governess, common for a well-off family. Was education a ‘woman’s thing’, thus provoking the natural absence of the father?

In her text Jezzamathatics, Leonora talks about her birth as an unlikely event: her parents were not there, the only one present at that very important moment of life, was her dog, a fox- terrier called ‘Boozy’. Being a parody of the artist’s statement, the text suggests the absence of and the liberation from both the father and the mother.

The young Leonora freed herself from the familiar context, challenged the limits of her gender and found liberation in art and fiction. Her readings helped her flee the reality of high society. The young lady from her short story the Debutant stays reading Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels while her hyena friend puts on her clothes and takes her place at her party. As the debutant who realises that she doesn’t want to be part of a farce and prefers reading a book in her room – Leonora declared she was actually reading Aldous Huxley.3 The female characters in The Debutant, The Oval Lady and Penelope address resistance to adulthood, the female condition, forced unions and the absurd reduction of life to a bargaining object.

Leonora convinced her father and was able to enrol in the academy of the known painter Amedée Ozenfant in London, despite the fact that Mr. Carrington expressed that art was a ‘poor or homosexual’4 practice. The first International Surrealist Exhibition was inaugurated in 1936, at a time when Leonora was able to feel the resonance of the works of this movement with her own ideas and fantasies. She also had the opportunity to experience this important moment in art history from the inside, by the means of her relationship with Max Ernst and her friendship with artists such as Leonor Fini, Man Ray, Lee Miller and André Breton.

Leonora Carrington’s feminist consciousness was born early on, considering the difference between her brothers’ education and her own, the only daughter of four kids. The early awareness of the iniquity between men and women fed her uncompromising rebellion and nonconformism. Her brothers had the right to play certain games that she could not play. Indeed, the abyss between men’s and women’s condition in British high society of the early 20th century could be hardly trespassed.

Leonora had to be educated in order to be a ‘lady’ and to be introduced to the court. While women’s education consisted of learning to read and write, learning French and basic mathematics skills, the access to art and science was strictly limited to men.

A natural since her childhood, Leonora Carrington had the attributes of superior intelligence: she drew, created stories, was ambidextrous and she wrote backwards, as Leonardo da Vinci did, so that her writing could be read in a mirror. Her mind went beyond the etiquettes she had to learn in the religious schools she attended, beyond good manners and high society’s conventions. A great mind, ill-adjusted to the rules since her childhood, expelled from various Catholic institutions. Women’s education by women could also had formed her feminine consciousness: the Irish legends of Tuathá de Dana’s White Goddess that her mother and her nun used to tell her, along with her French governess, common for a well-off family. Was education a ‘woman’s thing’, thus provoking the natural absence of the father?

In her text Jezzamathatics, Leonora talks about her birth as an unlikely event: her parents were not there, the only one present at that very important moment of life, was her dog, a fox- terrier called ‘Boozy’. Being a parody of the artist’s statement, the text suggests the absence of and the liberation from both the father and the mother.

The young Leonora freed herself from the familiar context, challenged the limits of her gender and found liberation in art and fiction. Her readings helped her flee the reality of high society. The young lady from her short story the Debutant stays reading Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels while her hyena friend puts on her clothes and takes her place at her party. As the debutant who realises that she doesn’t want to be part of a farce and prefers reading a book in her room – Leonora declared she was actually reading Aldous Huxley.3 The female characters in The Debutant, The Oval Lady and Penelope address resistance to adulthood, the female condition, forced unions and the absurd reduction of life to a bargaining object.

Leonora convinced her father and was able to enrol in the academy of the known painter Amedée Ozenfant in London, despite the fact that Mr. Carrington expressed that art was a ‘poor or homosexual’4 practice. The first International Surrealist Exhibition was inaugurated in 1936, at a time when Leonora was able to feel the resonance of the works of this movement with her own ideas and fantasies. She also had the opportunity to experience this important moment in art history from the inside, by the means of her relationship with Max Ernst and her friendship with artists such as Leonor Fini, Man Ray, Lee Miller and André Breton.

Nevertheless, many surrealists, as modern as they were, still carried the reminiscences of the patriarchal mentality. How many gifted women were overshadowed by the great male figures of modernity? The very Remedios Varo who shared her life at the time with Benjamin Péret felt intimidated by André Breton and Paul Eluard.

The young Leonora who ran away with an older man, probably suffered the affronts of the personality of the already well-known German painter. Some biographers affirm that when Ernst ran out of new canvasses, he painted over Leonora’s works, playing with her mind. Still, beyond anecdotes, the surrealists kept her in their memory. She remains one of the two women included in Breton’s Anthology of Black Humour, along with Gisèle Prassinos, a fourteen-year-old poet. Two young poets who were almost kids. The idealisation of the femme enfant, the woman child – exacerbated nowadays by cinema and the fashion industry –has its origins with the surrealists, the archetype of the sensual and innocent muse that stirs poetic inspiration. The freedom and grace of the twenty-year-old youngster remained certainly associated with her image. Even though a little later, during her Mexican exile, when Leonora authorised the publication of Down Below, she warned in a letter to her editor that she was no longer the same person that ‘passed through Paris’:

[…] I am no longer the young Beautiful woman that passed through Paris, in love –

I am an old woman who has lived enough and I have changed – If my life is worth something,

I am the result of time –So I will not reproduce the early image anymore – I will not be

petrified in a ‘youth’ that does not exist any longer. I accept today’s Honourable Decrepitude

– what I have to say now is revealed as much as possible – to see through the monster – Do

you understand that? No? Never mind. Anyway, do what you want with this ghost –

under the condition

that you publish

this letter as a preface –

[…]

P.S. If the young people say that I have a young mind, I take offence –

I have an OLD MIND […] 5

The twenty-two-year-old who lived through the World War II declaration and fled Europe’s conflicts grew old fast. She became a mother. Between the forties and the fifties, she wrote an ode to her friendship with Remedios Varo in her novel The Hearing Trumpet. She imagined their alter egos escaping from an old people’s home; two ninetyish friends who do not trust anyone between seven and seventy years-old, unless they are cats.

There were mainly three female archetypes cherished by the surrealists: the femme enfant, the femme fatale and the femme sorcière [the sorceress]: the childish woman, the seductive woman and the frightening woman. Nevertheless, roles and archetypes, all those incomplete figures of the female, are reductive enough for a lifetime, so perhaps Leonora Carrington’s privilege was that of having passed through them with curiosity, beauty and consciousness.

Art history testifies about women’s marginality, yet Leonora Carrington’s strong character went beyond the feminism that recognises that men are not superior to women. Leonora Carrington transcended not only genders but also species: If gods exist, I don’t believe they have human form: I prefer to envision deities with the appearance of zebras, cats, or births. Love guides all these species: only man makes a deity of Hate with his wars, his puritanism, the oppressions against his own species and the nature

around him. Man feels he is the king of the earth because he has had the power to destroy plants, animals and himself.6

Leonora Carrington undoubtedly recognised the value of life and emotions of any living thing, the value of the conscience of paradise on earth, of what Dante paraphrased as that ‘which moves the sun and the other stars’:7

I believe that in the beings’ life love exists and there can be different types of love, until you get to an indefinite age […] but in passion-love it is the beloved, the other, who gives the key.8

Art history testifies about women’s marginality, yet Leonora Carrington’s strong character went beyond the feminism that recognises that men are not superior to women. Leonora Carrington transcended not only genders but also species: If gods exist, I don’t believe they have human form: I prefer to envision deities with the appearance of zebras, cats, or births. Love guides all these species: only man makes a deity of Hate with his wars, his puritanism, the oppressions against his own species and the nature

around him. Man feels he is the king of the earth because he has had the power to destroy plants, animals and himself.6

Leonora Carrington undoubtedly recognised the value of life and emotions of any living thing, the value of the conscience of paradise on earth, of what Dante paraphrased as that ‘which moves the sun and the other stars’:7

I believe that in the beings’ life love exists and there can be different types of love, until you get to an indefinite age […] but in passion-love it is the beloved, the other, who gives the key.8

1. The work’s title has been previously translated as ‘Women Awareness’, although it does not translate the polysemy of the Spanish title: the word ‘conciencia’, meaning ‘awareness’, ‘conscience’ or ‘consciousness’ can also be phonetically interpreted as Women with science (mujeres con ciencia). Many thanks to Katelyn Butcher and Pierre Taminiaux for their help with the English translation of this article.

2. Germaine Rouvre’s interview with Leonora Carrington, published in La femme surréaliste, n. 14-15 Obliques, Nyons, 1977, p. 91.

3. Leonora declared she was reading Aldous Huxley’s Eyless in Gaza, c.f. Leonora Carrington--the Mexican years, 1943-1985. , San Francisco; Albuquerque, N.M., Mexican Museum ; Distributed by the University of New Mexico Press, 1991, p. 34.

4. Marina Warner’s introduction to Leonora Carrington, Down below, New York Review Books, New York, 2017, p. xvii.

5. Letter from Leonora Carrington to Henri Parisot [unpublished KSP’s translation from the French], in Leonora Carrington, En Bas, Paris, E. Losfeld, 1973.

6. Quoted by Giulia Ingarao, ‘From Europe to Mexico’, in the exhibition’s catalogue Leonora Carrington, Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2013. p.72

7. Last verse from Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, Paradiso, canto XXXIII,145.

8. Germaine Rouvre’s interview with Leonora Carrington, op. cit.