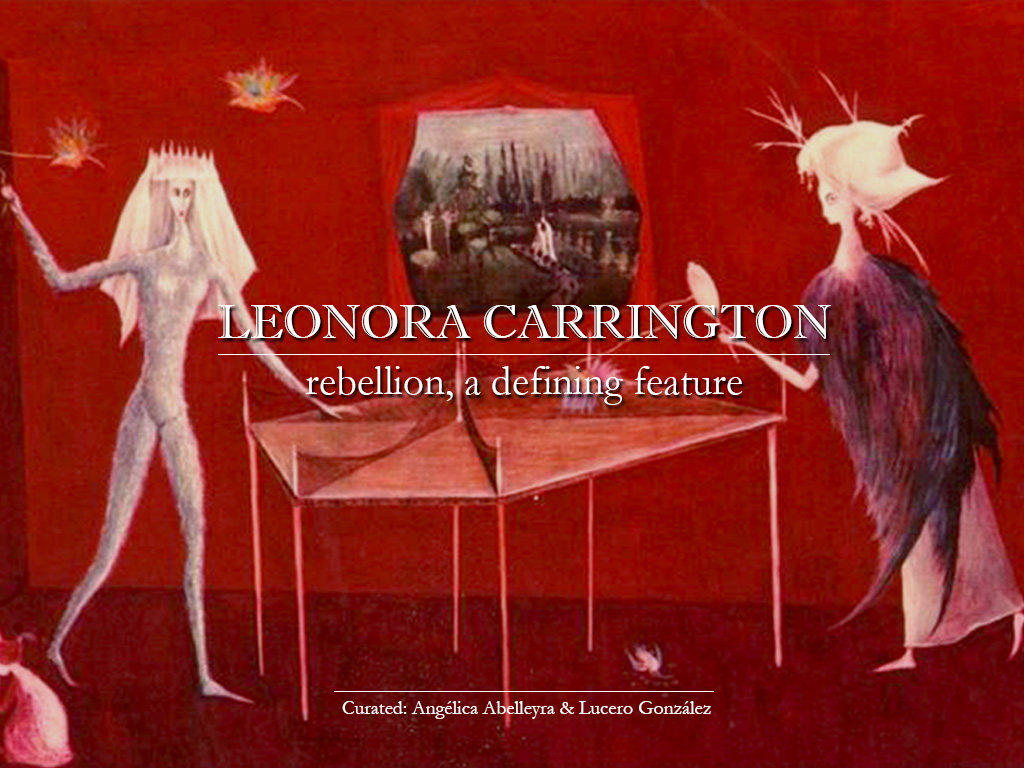

Leonora Carrington: Rebellion, a defining feature

|

|

LEONORA CARRINGTON: Title and two initial extracts of the essay included |

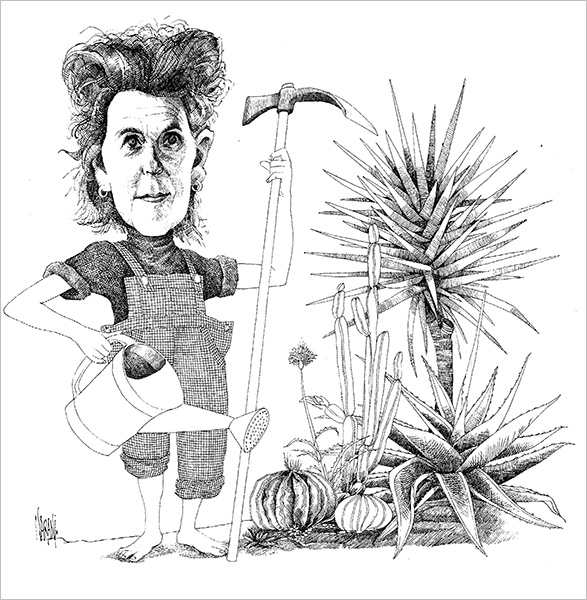

Rogelio Naranjo, La insurrección de las semejanzas, UNAM, Coordinación de Difusión Cultural, Dirección de Literatura, CU, Mexico, City, 2005 |

|

Why not grant the most humble objects cosmic powers? Why not create a universe of priestesses and ghosts? Why not try to uncover a complex side of the world, to save us from traps? |

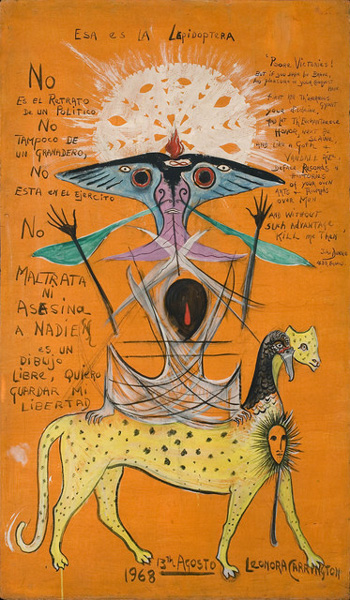

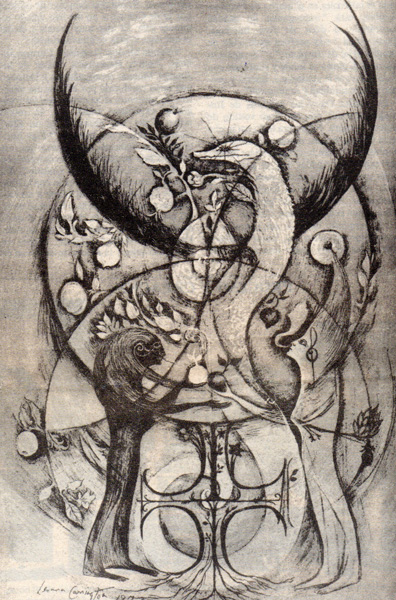

Lepidóptera, 1968. Leonora Carrington |

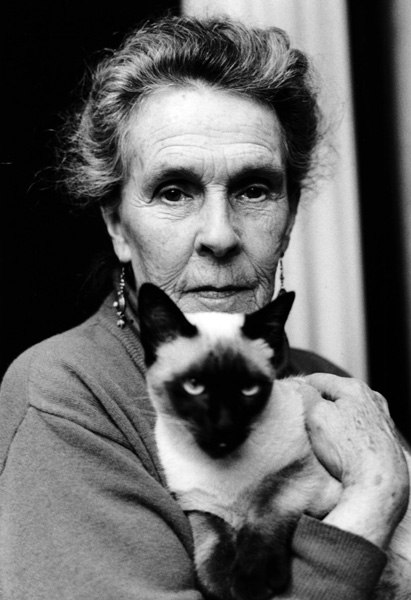

Photo by Lucero González. 1993 |

Rebellious and immune to simplification, Leonora Carrington (1917) has always asked these questions. Without producing clear answers, the English painter recreates them repeatedly in paintings, sculptures and etchings. “For me, color, matter and cloth have become my connection with the world. Beyond a language, painting is a way of life”. |

Mujer conciencia, 1972. Leonora Carrington |

LEONORA CARRINGTON: 1. The work’s title has been previously translated as Women Awareness, although it does not translate the polysemy of the Spanish title: the word ‘conciencia’, meaning ‘awareness’, ‘conscience’ or ‘consciousness’ can also be phonetically interpreted as Women with science (mujeres con ciencia). Many thanks to Katelyn Butcher and Pierre Taminiaux for their help with the English translation of this article. |

|

In several interviews and testimonies, Leonora Carrington declares being conscious of the obstacles and difficulties related to the female artist’s condition. The sharp consciousness of the differences is the background of her biography and artwork. Even if Leonora Carrington did not affiliate definitively to any feminist movement, as a woman, she never stopped questioning ‘why we were considered as inferior beings?’2 2. Germaine Rouvre’s interview with Leonora Carrington, published in La femme surréaliste, n. 14-15 Obliques, Nyons, 1977, p. 91. |

Leonora had to be educated in order to be a ‘lady’ and to be introduced to the court. While women’s education consisted of learning to read and write, learning French and basic mathematics skills, the access to art and science was strictly limited to men. |

|

In her text Jezzamathatics, Leonora talks about her birth as an unlikely event: her parents were not there, the only one present at that very important moment of life, was her dog, a fox-terrier called ‘Boozy’. Being a parody of the artist’s statement, the text suggests the absence of and the liberation from both the father and the mother. 3. Leonora declared she was reading Aldous Huxley’s Eyless in Gaza, c.f. Leonora Carrington--the Mexican years, 1943-1985., San Francisco; Albuquerque, N.M., Mexican Museum ; Distributed by the University of New Mexico Press, 1991, p. 34. |

Leonora convinced her father and was able to enrol in the academy of the known painter Amedée Ozenfant in London, despite the fact that Mr. Carrington expressed that art was a ‘poor or homosexual’4 practice. The first International Surrealist Exhibition was inaugurated in 1936, at a time when Leonora was able to feel the resonance of the works of this movement with her own ideas and fantasies. She also had the opportunity to experience this important moment in art history from the inside, by the means of her relationship with Max Ernst and her friendship with artists such as Leonor Fini, Man Ray, Lee Miller and André Breton. Nevertheless, many surrealists, as modern as they were, still carried the reminiscences of the patriarchal mentality. How many gifted women were overshadowed by the great male figures of modernity? The very Remedios Varo who shared her life at the time with Benjamin Péret felt intimidated by André Breton and Paul Eluard. 4. Marina Warner’s introduction to Leonora CARRINGTON'S, Down below, New York Review Books, New York, 2017, p. xvii. |

|

The young Leonora who ran away with an older man, probably suffered the affronts of the personality of the already well-known German painter. Some biographers affirm that when Ernst ran out of new canvasses, he painted over Leonora’s works, playing with her mind. Still, beyond anecdotes, the surrealists kept her in their memory. She remains one of the two women included in Breton’s Anthology of Black Humour, along with Gisèle Prassinos, a fourteen-year-old poet. Two young poets who were almost kids. The idealisation of the femme enfant, the woman child – exacerbated nowadays by cinema and the fashion industry – has its origins with the surrealists, the archetype of the sensual and innocent muse that stirs poetic inspiration. The freedom and grace of the twenty-year-old youngster remained certainly associated with her image. Even though a little later, during her Mexican exile, when Leonora authorised the publication of Down Below, she warned in a letter to her editor that she was no longer the same person that ‘passed through Paris’: |

[…] I am no longer the young Beautiful woman that passed through Paris, in love – 5. Letter from Leonora Carrington to Henri Parisot [unpublished KSP’s translation from the French], in Leonora Carrington, En Bas, Fontaine, Paris, 1945. |

|

The twenty-two-year-old who lived through the World War II declaration and fled Europe’s conflicts grew old fast. She became a mother. Between the forties and the fifties, she wrote an ode to her friendship with Remedios Varo in her novel The Hearing Trumpet. She imagined their alter egos escaping from an old people’s home; two ninetyish friends who do not trust anyone between seven and seventy-seven-years-old, unless they are cats. |

Art history testifies about women’s marginality, yet Leonora Carrington’s strong character went beyond the feminism that recognises that men are not superior to women. Leonora Carrington transcended not only genders but also species: 6. Quoted by Giulia Ingarao, From Europe to Mexico, in the exhibition’s catalogue Leonora Carrington, Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2013. p.72 |

L'amor che move il sole e l'altre stelle, 1946. Leonora Carrington |

|

Leonora Carrington undoubtedly recognised the value of life and emotions of any living thing, the value of the conscience of paradise on earth, of what Dante paraphrased as that ‘which moves the sun and the other stars’:7 7. Last verse from Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, Paradiso, canto XXXIII,145. |

|

THE CHTHONIC REALMS OF It gives me so much pleasure to be here today with so many like-minded people who love Leonora and her work. It is so gratifying to witness how every year so many new young scholars, collectors, and creators from all parts of the world become inspired by Carrington and go on to explore different aspects of her output. Leonora Carrington is one of those artists that people feel passionately about, and I can understand that. Seeing her work for the first time for me was a revelation. It was 1985 and I was beginning graduate school and by chance I happened to walk into Brewster Fine Arts, her New York City gallery at the time. I don’t recall what exactly I saw, but I do remember being literally rooted to the spot, having a hard time breathing, and deciding right there and then with great conviction that I would write my Ph.D. Dissertation on her work. And I did, but it wasn’t easy. |

Mostly it was Leonora who proved to be difficult! She would occasionally come to her openings at Brewster and we would sneak cigarettes together in the stairwell, but she refused to speak about her art. She hated art historians and had no trouble communicating that to me. I wanted to tell her - hey, I’m different – but I found that hard to do because truthfully I wondered, am I any different from those who came before me? After studying some of the things written about her early on, I could understand her hostility. So, I did a lot of soul searching about my intentions, not only as an art historian, but also as a person. When I finally did gain her trust and began to work with her more seriously, I felt I had passed a secret initiation of sorts. I was careful not to abuse her trust because I came to understand that underneath her legendary fierceness was great vulnerability. To say that I learned much from her, as an artist and even more as a person, is an understatement. |

Sachiel, Angel of Thursday, 1967. Leonora Carrington |

|

Although I have spent a good portion of the past twenty years looking at and thinking about the works of Leonora Carrington, what always impresses me is how much there is still left to investigate. At times I think that we have barely scratched the surface of all that her work has to offer. Why is it that every time I look at one of her paintings I end up saying to myself – how could I have not seen that before! For a curious aspect of her work, for me at least, is that it reveals itself in stages, over time. I would like to briefly share with you a few recent cases where she has surprised me more than usual. I had long admired this 1967 painting, Sachiel, Angel of Thursday, but any sense of its’ meaning had eluded me. As I began to re-examine it, I thought about the clue given in its title. In Kabbalistic and Christian angelology Sachiel is a powerful archangel associated not only with the day of the week Thursday, but also with the planet Jupiter and the astrological sign of Sagittarius, and is often invoked for prosperity. It is not enough to get out a magnifying glass, Carrington’s work is so complicated I often project it onto the wall and now with the computer I can enlarge it, turn it backwards, upside down, etc. For the first time I noticed some marks in the corner outside of the black magic circle above. |

Detail of Leonora Carrington, Sachiel with Sigil |

|

Low and behold, completely invisible to me for years, was Sachiel’s sigil. In magic a sigil is a special sign used either for protection or to call forth special entities into being. They can be found in certain historical texts and her friend, the Swiss surrealist Kurt Seligmann, discusses them in his book The Mirror Of Magic, a book she owned and loved. |

Ropa Vieja , 1968. Leonora Carrington |

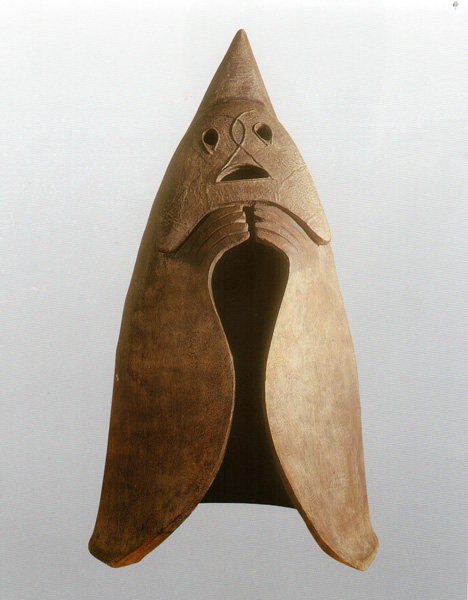

The Ancestor, 1968. Leonora Carrington |

Another recent surprise Carrington gave me was in a group of works from 1968 and 69, once again revealing not only her great knowledge of many esoteric traditions, but her political involvements. Ropa vieja is a charming drawing that is probably a disguised self-portrait as Carrington did not like to portray herself. Flapping on a clothesline along with a prosaic pair of pants is a long hooded white robe. Although today we might associate it with a burka, for Carrington in 1968 it probably had a number of other associations, such as a special robe worn in magical workings or perhaps on a more amusing level a bed sheet, thrown over oneself as a ghost costume for Halloween or, more seriously, as a disguise during politically turbulent times. The lacey decoration around the eyes made me immediately think of another painting she did during that turbulent year, The Ancestor. |

|

1968 was a year of global political turmoil and Carrington had two young sons in their twenties and naturally she was concerned about them and the world they lived in. In the midst of all this frenetic energy in the world she painted the monumental The Ancestor that is reminiscent of an altarpiece, although decidedly not a traditional Christian one. This sole figure hovers at the crossroads of time and space, observing us with a cool detachment. The draped ghost-like figure has a comical aspect, but again, under Carrington’s humor is a dead seriousness. A number of factors contribute to its arresting psychic impact, for example the masterful way it blends traditional religious painting with the occult. It is also another one of Carrington’s invocation pieces where an entity floats in the middle of the magic circle used to summon it. There is a sense of the picture being alive and looking back at us that is uncanny and disquieting. This emissary from the past emerges momentarily in a cloud of nebulous golden light, before departing to other dimensions. This work led me to think of another work, rarely exhibited and hidden away in a private collection. |

Untitled, 1969. Leonora Carrington |

|

Painted the following year in 1969, this untitled painting obviously shares many features with The Ancestor, but also had something unique. I saw it once many years ago, and recalled that there was writing at the bottom that was almost impossible to see in a reproduction. I think that her embedded texts in paintings are one of the important aspects of her work that needs further exploration. But it is difficult because you often do not even know the writing is there until you see the work in person. I had to badger the poor owner of this work and forced her to take pictures of the text and send them to me - thank God for cell phone cameras! When I pieced together the many close-ups and projected them (the texts were of course upside down and backwards) a rather surprising inscription confronted me. At the feet of the figure is a dove with its heart ripped out and spelled out in its blood carefully is the date 2nd Oct 1968. Under that is written: |

“By the river of Yggdrasill, there we sat down, yea we wept because they are murdering our sons, our daughters, the birds and the fishes and trees of the earth. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof for they that carried us away captive required of us songs – they that wasted us required of us mirth.” The text is clearly taken from Psalm 137 of the King James Bible, with some significant variations. In typical fashion Carrington has altered the text to reflect her lament that all life is in peril not just human but animals, trees, nature itself. In this context the use of Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life from Norse mythology, makes sense. Carrington leaves us a literally a bloody clue with which to unlock the mystery – that is the date October 2 1968, when students and civilians in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas were gunned down by the Mexican military in what is now known as the Tlatelolco Massacre. |

The Ancestor, 1968. Leonora Carrington |

Untitled, 1969. Leonora Carrington |

|

When you view them together, you can see that this 1969 untitled painting is clearly the companion piece to The Ancestor. It is even more magically charged and the circle has moved up off the floor and up to its chest, its concentric circles filled with wavy lines representing the element of water. The four corners have expanded to create a threshold from which the figure appears to actively step forth from while at the top agitated creatures move about. The apparition reveals itself to be female and holds a fifth lemur in her arms, a sly nod to the Virgin and Christ child. An ethereal white snake wraps itself around her, a spiritual protector, not an evil tempter. Bathed in a soft lavender light she has a mystic red third eye, which emits a stream of light that curls up like smoke. Her own eyes are wide open and she observes us with sorrow, as the dove of peace lies cruelly murdered at her feet. Carrington painted this in New York City where she moved to after the political unrest of Mexico. It is unclear what Carrington intended her manifestation to do – to protect, to avenge to offer solace or simply to witness. And finally, that red dot on her forehead made me think of another work. |

The Magdalens, 1986. Leonora Carrington |

|

Like the works we have seen before, The Magdalens is both esoteric and political, and if anything even more relevant today than when it was painted in 1986. Carrington again uses humor to cover the darker more chthonic aspects of feminine power – for we are clearly in a cavernous subterranean space that, with its underground river and Egyptian sarcophagus, suggests the underworld. There are allusions to Persephone in the underworld, to the underground dwellings of the Sidhe of Ireland, and of course Xibalba, the underworld of the Maya. But that is really all extraneous, for what is important is that it is a chthonic realm, populated by women, who are involved with exchanging power substances - herbal remedies, drugs to promote shamanic visions, or knowledge itself. |

In that case, birth control pills are most certainly a sacred substance, both for women’s reproductive rights and for the ecological salvation of our planet. And recently, thinking about the title, I wonder if this painting covertly refers to the terrible Irish Magdalene laundries run by the Catholic church where women and girls who were deemed a threat to the moral fiber of society were imprisoned without trial or recourse until as late as 1996 when they were finally abolished. Single mothers, illegitimate children, prostitutes and women considered promiscuous and undesirable were made invisible, wasting away in a life of hard labor and confinement. Although we don’t think of Carrington as a political artist, was she transforming the “lowest” of women into the keepers of sacred knowledge? Again, there is still so much more work to do and now with the formation of the Leonora Carrington Foundation, we can be more secure that archives that would help us all in our research are being made more secure for future generations. |

Casa de los espíritus, bronce, 2004-2005. 219 X 133 X 100 cm. Leonora Carrington |

|

© Estate Leonora Carrington / ARS for all Leonora Carrington works. |