Vulnerability and Resistance

Thinking along with Butler: some points about the conference “Vulnerability and Resistance Revisited.”

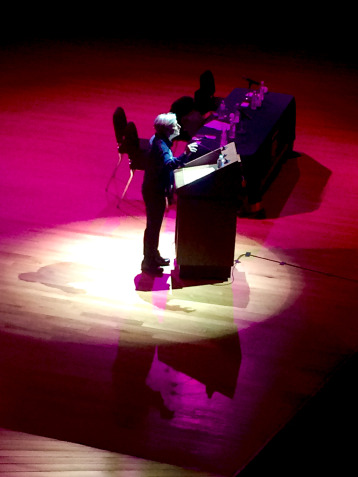

Judith Butler visited our national university (UNAM) to present the conference “Vulnerability and Resistance Revisited” at the impressive Nezahualcóyotl auditorium, where she offered an outlook of her corpus of work around these notions. Several of her texts have accompanied me in my classes and writings throughout my professional life. I’m here offering you a text with some of the points that, personally, were exciting to listen on the flesh, from one of the most prolific and outstanding contemporary philosophers of our time.

Butlerand her projections

Decisive start: bring Ayotzinapa as a symbol to initiate her speech. The audience briefly applauded, to avoid interrupting her, as a way of showing her their appreciation for her acknowledgement through mentioning one of the most painful cases in our political life. Even when in Mexico certain institutions with political and economical interests try to deny the current situation, Butler insists:

“So, there is no way to come to Mexico during this times without participating, as we do today, in a collective act of grieving, but also without joining in solidarity with those who demand full disclosure to what has happened to those students, and full justice, which means bringing all those responsible for their fates to justice. How can there be justice when those who are in power are the ones who are unjust? How can there be demonstrations when the police who are supposed to protect that right of assembly, detain, disperse, harass, injure and even kill those who exert that very right? At the moment in which the people cannot rely in the law, the law has emancipated the people to create their own political future. When the law is in itself a violent regime, one has to oppose the law in order to, paradoxically, to oppose violence.There is not forgetting, there is no end to this demand for justice for all of us.”

Fearless, Butler opens the topic calling for the power of protesting to start her statement. I recall about the reserves that public figures, citizens, and other foreign visitants have when they are addressed about this topic. Most of them avoid mentioning it.

Listening to Butler talking about the notion of protest turns out to be fundamental because she reminds us that it constitutes one of our basic human rights. When I heard it, outspoken like that, explicitly as a human right, it emphasizes the state of urgency that we lived at in our country. It is not gratuitous that one of the most important movement of citizens in Mexican contemporary history is being consolidated, some times not with the speed that we would like or with the immediate results, but from my point of view, the change in this society is tangible.

Facing the state of terror imposed by the current political organisms, Butler’s words echo in my experience of this reality. She warns that in other latitudes, as much as in this country, demonstrations in public spaces open a potential threat. The risk of being imprisoned, hurt or harassed constitutes a high stake in this country. This possibility, as we now by the forty-three case, feminicides, and attacks on freedom of expression and murder and threats to journalists, is frequently and savagely exerted in our country.

When thinking with Butler, we also have to notice the differential distribution of violence. The precarity to which certain groups are exposed is clearly higher, such as the students in a rural context, and the criminal police groups consider it more plausible. It seems to me that although, demonstrations in Mexico City regretfully have been repressed by the police, public gathering in other Mexican cities shows the increase of the potential risk that effectively exists, as we can testify through Youtube videos. The case of the 43, the assassinated women, and even the assassination and harassment of their families claiming for justice, exhibit the condition of risk in this country. It is necessary to think about politics with the tools offered by this theorist in order to read these painful situations in all their complexity, with its texture and its nuances.

I want to clarify that it is not my intention to minimize the importance of each one of the levels of repression that we have experienced all around the country, because all of them come from the same source: human right violations, in which in fact there is a dangerous exposition. The least sordid scenario goes from the intimidation by the police forces while families and civilians, children and elders, people in wheel chairs and dancing students were marching at our main avenue, Reforma. As we experienced, it escalated when this same police forces illegally detained, beat and violently arrested these same people at the main plaza. This happened to one of my students when she was practicing her profession by doing a photo-article in Mexico City, while she was in the demonstrations for justice with the Ayotzinapa parents. Butler would say that this young woman in the practice of her profession, in her presence of such political events, with her body and agency resisted from her vulnerability to the violent exercise of power.

Listening to Butler talking about the notion of protest turns out to be fundamental because she reminds us that it constitutes one of our basic human rights. When I heard it, outspoken like that, explicitly as a human right, it emphasizes the state of urgency that we lived at in our country. It is not gratuitous that one of the most important movement of citizens in Mexican contemporary history is being consolidated, some times not with the speed that we would like or with the immediate results, but from my point of view, the change in this society is tangible.

Facing the state of terror imposed by the current political organisms, Butler’s words echo in my experience of this reality. She warns that in other latitudes, as much as in this country, demonstrations in public spaces open a potential threat. The risk of being imprisoned, hurt or harassed constitutes a high stake in this country. This possibility, as we now by the forty-three case, feminicides, and attacks on freedom of expression and murder and threats to journalists, is frequently and savagely exerted in our country.

When thinking with Butler, we also have to notice the differential distribution of violence. The precarity to which certain groups are exposed is clearly higher, such as the students in a rural context, and the criminal police groups consider it more plausible. It seems to me that although, demonstrations in Mexico City regretfully have been repressed by the police, public gathering in other Mexican cities shows the increase of the potential risk that effectively exists, as we can testify through Youtube videos. The case of the 43, the assassinated women, and even the assassination and harassment of their families claiming for justice, exhibit the condition of risk in this country. It is necessary to think about politics with the tools offered by this theorist in order to read these painful situations in all their complexity, with its texture and its nuances.

I want to clarify that it is not my intention to minimize the importance of each one of the levels of repression that we have experienced all around the country, because all of them come from the same source: human right violations, in which in fact there is a dangerous exposition. The least sordid scenario goes from the intimidation by the police forces while families and civilians, children and elders, people in wheel chairs and dancing students were marching at our main avenue, Reforma. As we experienced, it escalated when this same police forces illegally detained, beat and violently arrested these same people at the main plaza. This happened to one of my students when she was practicing her profession by doing a photo-article in Mexico City, while she was in the demonstrations for justice with the Ayotzinapa parents. Butler would say that this young woman in the practice of her profession, in her presence of such political events, with her body and agency resisted from her vulnerability to the violent exercise of power.

“They are just missing to prohibit us to cry to ripp us our hearts” Photo: Fabiola Aguilar

While listening to the conference, I remembered the feeling of being in the protests in Mexico City and I was moved. We have gathered in the streets, some times among dear friends and my students that for the first time went to a demonstration, breaking the normativity of the status quo reinforced by the media. Courageously, they wanted to directly experience these demonstrations and take part of this demand for justice. We walked carefully, in a festive ambiance, but at the same time with the fear and rage that caused us a lump in our throat. This exacerbated violence is not irrelevant to each of us who was there taking the streets; nevertheless, we exposed our vulnerable bodies, as the author says. Even after the violence showed before by the state, we went out with this in mind and embedded in our body. Our senses learnt to be at a constant alert that for sure is compensated with the joy of meeting each other, listening to each other, performing, singing and counting from 1 to 43, and standing out in these citizen protests in an ambience of festive resistance.

Butler reminded us in the conference that norms are also exerted on us through the use of language, they act upon us; but that we also act by the language, therefore we act upon someone else when using it.

“As I try to suggest by all intention to the dual dimension of performativity we are invariably acted upon, and acting. And this is one piece of my (theory of) performativity cannot be reduced to the idea of free individual performance. We are called names, we find ourselves living in a world of categories and descriptions way before we start to sort them critically, and endeavor to change, or make them of our own. In this way, we are quite, in spite of ourselves, vulnerable to and affected by discourses that we never chose.”

We need to question the use of these phrases as what they are, iterations from the political power intending to stabilize their violence. The philosopher reminded us the case of Pussy Riot that through their disruptive performances have made the State to enunciate phrases that heard from political instances speak for themselves: they accuse them of the “corruption of the men souls”. In spite of the efforts of the power institutions through the media to discredit the protest calling them “the ones who don’t want to work”, in spite of the hopelessness that drives a lot of the population to the indifference or the lack of involvement promoted by affirmations such as “demonstrations are useless,” or “the economy is in danger,” or “our safety depends on continuing as we are,” among the most common messages that are exerted upon us and to determine us, we decided to go out to the streets. We wanted to express with the body and to act with the voice, to count endlessly from 1 to 43 and to join together thousands of voices that shouted for justice. If, as this philosopher says, language exerts a framing for acting upon others and at the same time, constitutes a form of resistance, it is worth to ask to ourselves for which one we are letting ourselves being forged, and which speech is acting upon us. Language does not go unnoticed; it is agency.

The bodies that Butler calls upon are more honest. They demand to be recognized as vulnerable, as well as intrinsically interdependent to each other -intersubjective-, and in constant relation with social, material, economical and political infrastructure. “We cannot talk about the body without knowing what supports that body, and what its relation is to that support or lack of support.” This has also been pointed out in other of her texts: precarity is induced, because above all, we are socially interdependent human beings. And, as a consequence, the power also needs us. In the streets we gather as human contingents, while Butler ask us to think that the vulnerability we feel shouldn’t be rejected. Personally, being gathered as a community against death in Mexico has constituted one of the most powerful embodied examples of the point this author is trying to make: “I want to argue against the notion that vulnerability is the opposite to resistance. Indeed, I want to argue affirmatively that vulnerability understood as a deliberate exposure to power is part of the very meaning of political resistance as an embodied enactment.”

From my point of view, introducing the category of vulnerability posits a revolutionary way of thinking political resistance. It opens possibilities to incorporate new readings of precarity conditions constructed in the personal milieu -that we already now that is indeed “the political”, according to the famous feminist phrase-. It means to rethink politics in a personal way from the vulnerability lived and precarity imposed in a deliberated way, for example, in the civil and legal scope that will enable some congruency in the social field. Because where, if it is not from the body and in the personal, do such vulnerability and its resistance inhabit and come from?

Butler reminded us in the conference that norms are also exerted on us through the use of language, they act upon us; but that we also act by the language, therefore we act upon someone else when using it.

“As I try to suggest by all intention to the dual dimension of performativity we are invariably acted upon, and acting. And this is one piece of my (theory of) performativity cannot be reduced to the idea of free individual performance. We are called names, we find ourselves living in a world of categories and descriptions way before we start to sort them critically, and endeavor to change, or make them of our own. In this way, we are quite, in spite of ourselves, vulnerable to and affected by discourses that we never chose.”

We need to question the use of these phrases as what they are, iterations from the political power intending to stabilize their violence. The philosopher reminded us the case of Pussy Riot that through their disruptive performances have made the State to enunciate phrases that heard from political instances speak for themselves: they accuse them of the “corruption of the men souls”. In spite of the efforts of the power institutions through the media to discredit the protest calling them “the ones who don’t want to work”, in spite of the hopelessness that drives a lot of the population to the indifference or the lack of involvement promoted by affirmations such as “demonstrations are useless,” or “the economy is in danger,” or “our safety depends on continuing as we are,” among the most common messages that are exerted upon us and to determine us, we decided to go out to the streets. We wanted to express with the body and to act with the voice, to count endlessly from 1 to 43 and to join together thousands of voices that shouted for justice. If, as this philosopher says, language exerts a framing for acting upon others and at the same time, constitutes a form of resistance, it is worth to ask to ourselves for which one we are letting ourselves being forged, and which speech is acting upon us. Language does not go unnoticed; it is agency.

The bodies that Butler calls upon are more honest. They demand to be recognized as vulnerable, as well as intrinsically interdependent to each other -intersubjective-, and in constant relation with social, material, economical and political infrastructure. “We cannot talk about the body without knowing what supports that body, and what its relation is to that support or lack of support.” This has also been pointed out in other of her texts: precarity is induced, because above all, we are socially interdependent human beings. And, as a consequence, the power also needs us. In the streets we gather as human contingents, while Butler ask us to think that the vulnerability we feel shouldn’t be rejected. Personally, being gathered as a community against death in Mexico has constituted one of the most powerful embodied examples of the point this author is trying to make: “I want to argue against the notion that vulnerability is the opposite to resistance. Indeed, I want to argue affirmatively that vulnerability understood as a deliberate exposure to power is part of the very meaning of political resistance as an embodied enactment.”

From my point of view, introducing the category of vulnerability posits a revolutionary way of thinking political resistance. It opens possibilities to incorporate new readings of precarity conditions constructed in the personal milieu -that we already now that is indeed “the political”, according to the famous feminist phrase-. It means to rethink politics in a personal way from the vulnerability lived and precarity imposed in a deliberated way, for example, in the civil and legal scope that will enable some congruency in the social field. Because where, if it is not from the body and in the personal, do such vulnerability and its resistance inhabit and come from?

Judith Butler in Mexico City started her conference questioning the importance of theoretically discussing upon these issues while facing the urgency that this situation demands. She forcefully answered in the context of basic human rights, something that still echoes in me: “Philosophy is not a luxury, it is our right to think.”

Thank you Judith Butler, for this conference and for your texts, in which we have walk together to indeed performing our right to think.

Fabiola Aguilar,

Independent researcher on art, film and mass media.

Translation by Aurea Jiménez Sánchez.

Fabiola Aguilar,

Independent researcher on art, film and mass media.

Translation by Aurea Jiménez Sánchez.